What is the Scientist’s Role in Addressing Misinformation?

Post Date: May 22, 2024 | Publish Date:

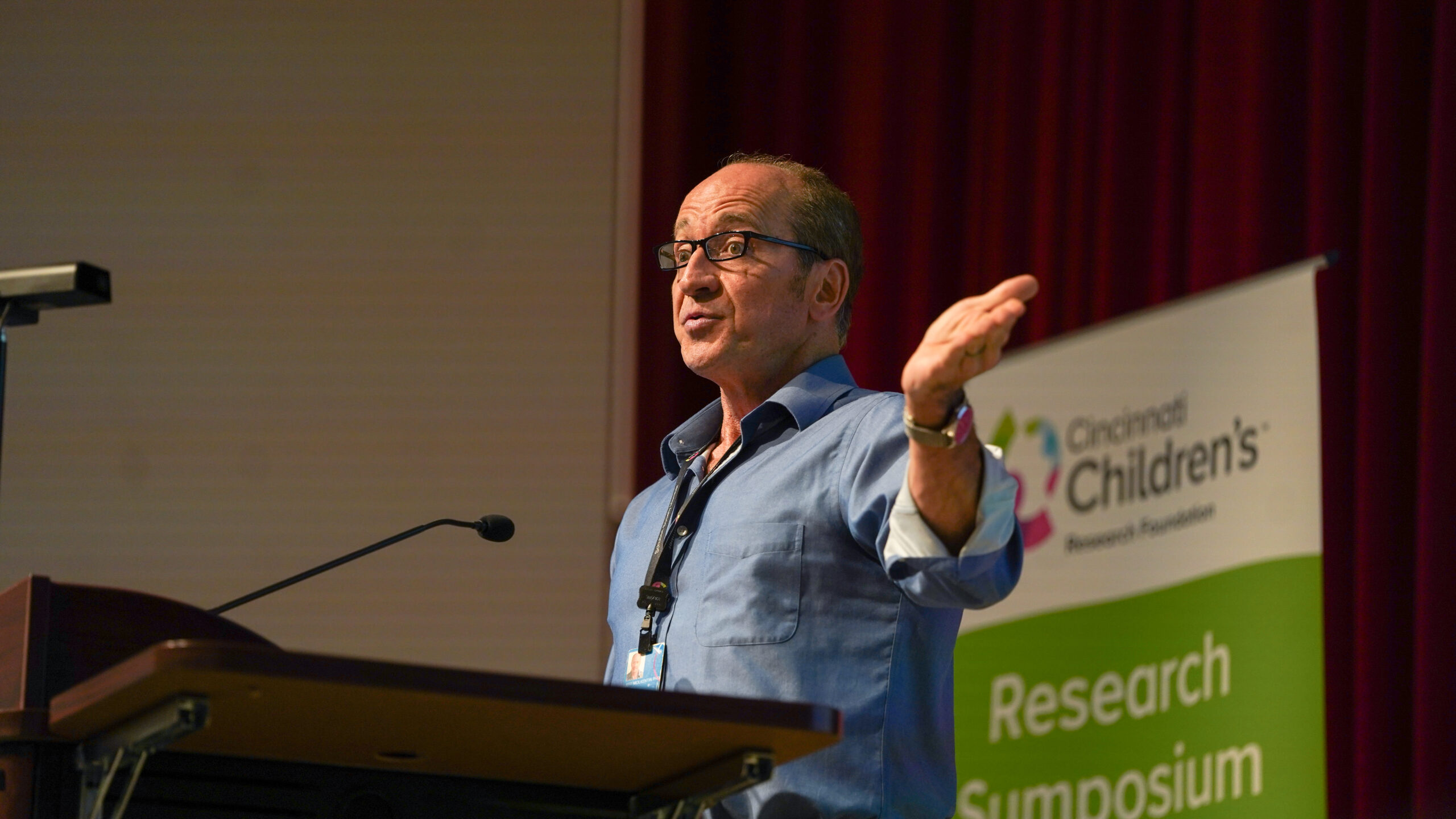

Second Annual Research Symposium at Cincinnati Children’s features widely acclaimed vaccine expert Dr. Peter Hotez

In Texas, as many as 40,000 people died in the COVID-19 pandemic after vaccines became widely available. Across the United States, choosing not to receive COVID vaccines cost about 200,000 people their lives.

That’s a conservative estimate, says Peter Hotez, MD, PhD, the featured speaker at a two-day research symposium held at Cincinnati Children’s. “Anti-vaccine activism is a real force, and it has become a killer. Now I realize that countering anti-vaccinism, in terms of saving lives, may turn out to be as important as actually making vaccines.”

Hotez is dean of the National School of Tropical Medicine at the Baylor College of Medicine, co-director of Texas Children’s Hospital Center for Vaccine Development, and author of several books including “Vaccines Did Not Cause Rachel’s Autism” (2018) and “The Deadly Rise of Anti-Science” (2023). He visited Cincinnati Children’s May 17, 2024, as part of the speaker series Envisioning our Future for Children.

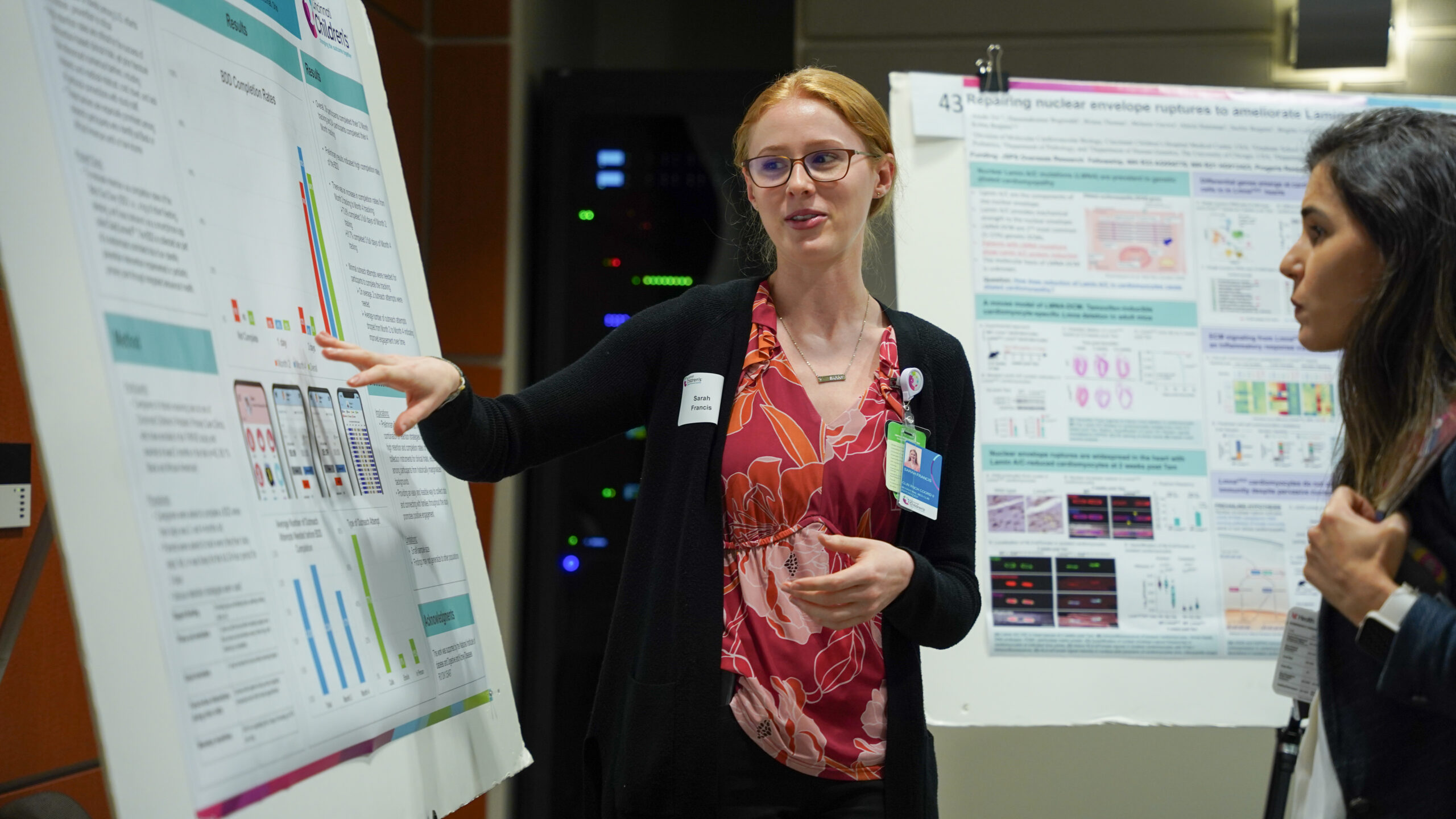

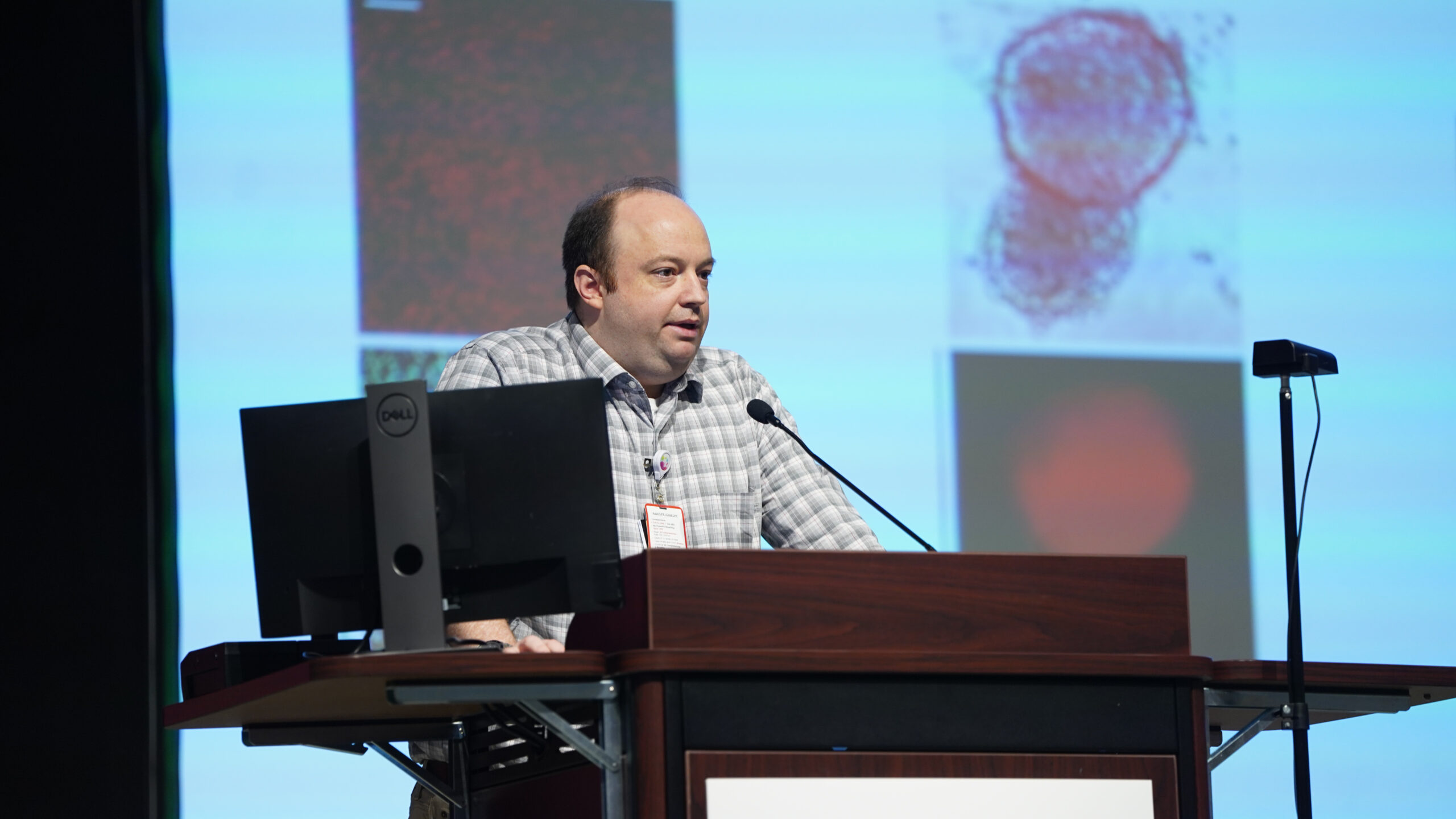

The symposium included Jeffery Molkentin, PhD, co-director of the Heart Institute at Cincinnati Children’s, who presented an overview of two decades of increasingly hopeful muscular dystrophy research. The event included a large poster session highlighting research at Cincinnati Children’s, as well as investigators providing updates about ongoing studies related to organoid development, advanced psychiatric care, pain management, repairing nerve damage, eosinophilic esophagitis, Fanconi anemia, and muscle strength and metabolism.

“Beyond the publications and the grants, it’s really about the impact that our work has on child health and on furthering science. That’s really what this symposium is all about,” says Tina Cheng, MD, MPH, chair of Pediatrics, director of the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation, and chief medical officer.

Continuing a legacy

Hotez noted that Cincinnati Children’s has a long history of advancement in vaccine development, including the legacy of Albert Sabin, MD, who developed the oral polio vaccine here decades ago. A crucial early step in launching that vaccine involved working with the Soviet Union at the height of the Cold War to deliver the vaccine to millions of Soviet children before it was approved in the U.S.

“That was the first proof of concept that the vaccine worked. It’s an example of two countries putting aside their ideologies to work together to make a life-saving vaccine, what I call vaccine diplomacy,” Hotez says.

Now, organizations such as the GAVI Alliance are striving to enable vaccine production using methods outside the traditional large pharmaceutical company model to bring affordable vaccines to nations with limited resources. Since the pandemic, global vaccination rates have fallen and vaccine development work has been hindered by what Hotez calls an organized anti-vaccine movement that is spreading to other nations.

What can academic medicine do?

Hotez acknowledges delving deeper into political issues than may be comfortable for many scientists. But when scientists do not speak out, he says, purveyors of misinformation speak unopposed.

Pediatricians already deal regularly with families being influenced by vaccine misinformation. In fact, Cincinnati Children’s has developed virtual reality tools to help clinicians practice discussions with skeptical parents.

Ultimately, politicians and the public will address the political issues swirling around child vaccination, Hotez says. Looking forward, he recommends that more physicians and scientists receive more public engagement training as part of their medical school and graduate program experiences.