Early Intervention for Children with Hearing Loss Improves Kindergarten Readiness

Research By: Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH

Post Date: September 28, 2020 | Publish Date: Sept. 28, 2020

When a child experiences hearing loss, early detection is key—intervention before the age of six months can lower the risk of language delays. From birth to three years old, the benefits of early detection and intervention show through improved language, social, and emotional development. But what happens when these kids reach kindergarten age?

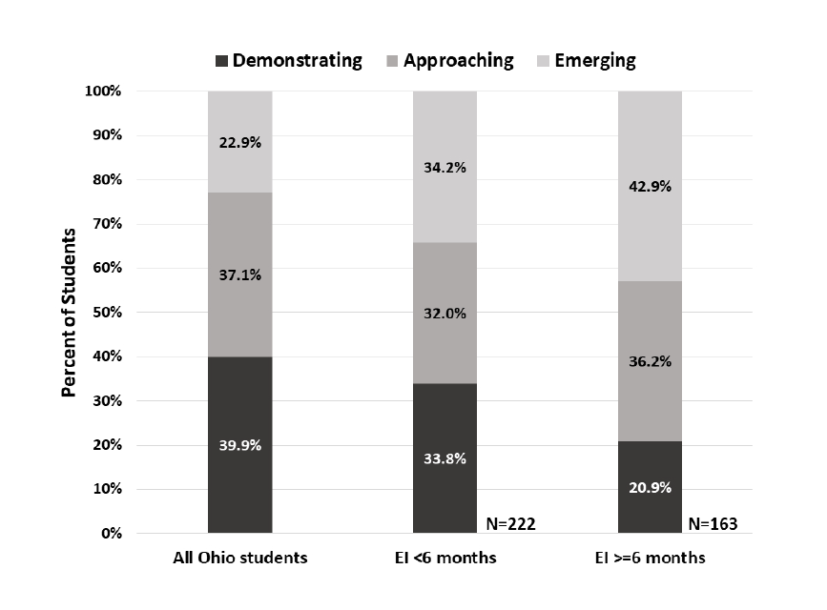

By combining public health and education data, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s tracked academic outcomes in deaf and hard-of-hearing children throughout Ohio. They found that children who received early intervention before the age of six months were more likely to be kindergarten-ready than children with later intervention, as published Sept. 28, 2020, in the journal Pediatrics.

Exploring the Long-Term Impacts of Early Intervention

For children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing, the time period between birth and three years of age is critical. This is when speech, language, and communication skills take some of the largest leaps. If hearing loss goes undetected, many children fall behind age-appropriate development levels.

As they grow, these early experiences help shape the foundational skills they’ll bring to school. Kindergarten readiness measures these skills by assessing four areas of early learning—social foundations, mathematics, language and literacy, and physical well-being and motor development.

Whether a child enters kindergarten “ready to learn” can affect their likelihood of academic success. Those who begin with the necessary skills are more likely to reach age- or grade-appropriate reading levels, which are essential for continued success throughout school.

Listen to Dr. Meinzen-Derr discuss her findings on the Pediatrics On Call podcast

In general, compared with their hearing peers, the majority of deaf or hard-of-hearing children are at risk to enter kindergarten with lower literacy skills. Throughout their academic years, they may continue to face higher risks for delays in communication, social, and academic skills. To improve these outcomes, we need to better understand the influence of early intervention experiences.

Linking the Data and Searching for Patterns

While strong evidence links early intervention to improved language outcomes, less is known about the association with early academic outcomes. Challenges in data sharing across public health and education systems leave questions about how early intervention could impact kindergarten readiness for children with hearing loss.

Thanks to their location, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s have an advantage in finding the answers. In the state of Ohio, all newborns are required to receive a hearing screening before they are discharged from the hospital as part of the Infant Hearing Program. The program also provides follow-up coordination for tracking and surveillance of infants who do not pass the screening test.

“We have the unique ability to study kids who were identified with hearing loss at birth through the Universal Newborn Hearing Screening program,” says lead author Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH, FACE. “By linking the data of these children to the school system, we have an opportunity to monitor their academic growth and development.”

To achieve this goal, the research team brought together data from three state agencies that work with children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing—the Ohio Departments of Health, Developmental Disabilities, and Education. The resulting database linked hearing screening and diagnostic data with early intervention and educational data.

Records from 1,746 infants identified with permanent hearing loss born between 2008 and 2014 were compared against kindergarten records. Children who received early intervention before the age of six months were more likely to demonstrate kindergarten readiness, regardless of hearing loss severity levels, race, and gender.

Establishing Healthy Trajectories of Development

How did these children beat the odds to remain on track with their hearing peers? While factors like insurance status, co-occurring disabilities, and unilateral or bilateral hearing loss played a role in overall outcomes, early intervention programs consistently demonstrated a lasting influence on the child’s ability to be ready for kindergarten.

Depending on the needs of each child and their family, the type of intervention they receive will vary. Interventions may focus on motor, speech, or developmental delays. These specialized services promote healthy language and communication development before delays occur.

To further understand how different interventions enhance academic readiness, the research team will continue following these kids through the third grade, tracking standardized test scores and reading levels. Another goal is to replicate the study on a newborn cohort as practices and policies change over time.

“When you’re a parent with a newborn, you might not think about what’s going to happen when they are in kindergarten, but this is why it’s very important to understand your child’s hearing screen results,” says Meinzen-Derr. “It is essential to receive a diagnosis and get them into early intervention if hearing loss is identified, even in infancy. We simply want to ensure that every child has the best opportunities possible in life.”

Resources for Families

-

Early Hearing Detection and Intervention (EHDI) state programs

-

Information on hearing screening and testing

-

Hands and Voices: Support for families of children who are deaf or hard-of-hearing

About the Study

Funding support for this research was provided in part by the Disability Research and Dissemination Center (U19DD001218 and U01DD001007), a unit of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

Post written by Dakota Campbell, Cincinnati Children’s

| Original title: | Kindergarten Readiness in Children Who Are Deaf or Hard of Hearing Who Received Early Intervention |

| Published in: | Pediatrics |

| Publish date: | Sept. 28, 2020 |

Research By