One Does Not Simply…Shut Down Science

Post Date: May 22, 2022 | Publish Date:

When the COVID-19 pandemic prompted Ohio Gov. Mike DeWine to issue “Stay at Home” orders on March 22, 2020, leaders at Cincinnati Children’s faced an enormous challenge: What does it mean to shut down research?

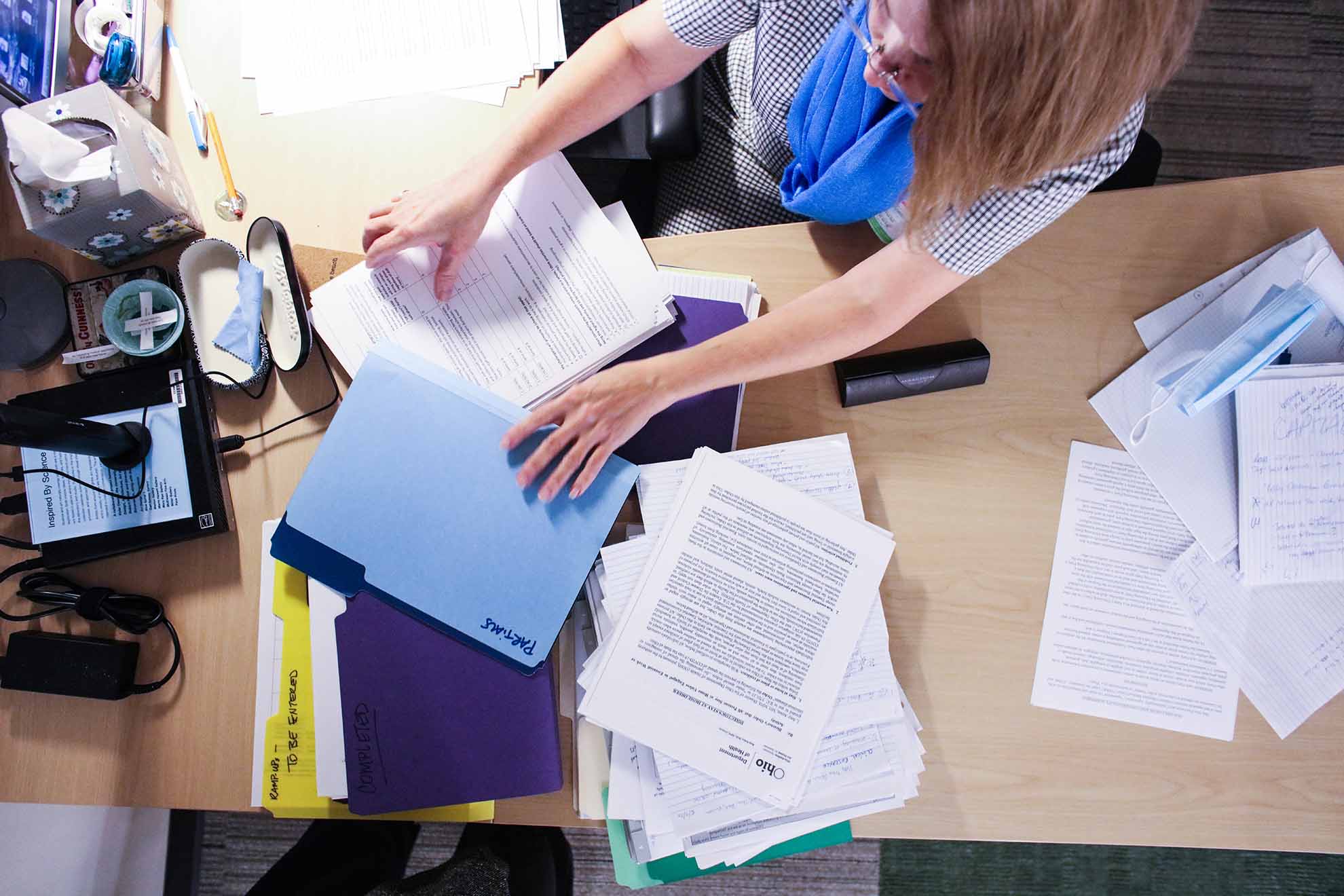

On a normal day, the Research Operations team under Kristine Justus, PhD, Vice President, spends its time ensuring researchers have what they need for each of their scientific programs.

Danny Burdine, MBA, Laura Runck, MSc, and Ryan Varney, MA, (aka the “Justus League”) partner with nearly every department at Cincinnati Children’s—Supply Chain, Plant Engineering, Marketing & Communications, ORCRA, OSEH, Environmental Services, Protective Services, Information Services, and others. They often work with third-party vendors to solve issues. They remove roadblocks, streamline processes, lead efforts in safety, assist with garnering and negotiating the best price for resources, and provide general communications across the research enterprise.

But this was not a normal day. A shut down is the antithesis of what the operations team does. When the Governor’s order was given, Justus’ first action was to get with her team and come up with a plan.

“We had two and only two goals. The first was to keep everyone safe,” she says. “The second was to minimize damages so that as soon as the Governor lifted the order, we would be poised for a rapid recovery.”

SHUTTING DOWN A COMPLEX ORGANIZATION WITH CARE

It’s not easy to shut down research. With clinical trials, and in particular interventional trials, it can be detrimental to just stop. It’s not reasonable to suddenly withhold a study drug from a study participant, for example.

Likewise, there are major challenges in a wet lab scenario: cell cultures need proper care and feeding, hazardous chemicals have to be handled, stored or disposed of appropriately, some instruments rely on static gas pressures or uninterrupted power, cold storage may need attention so as not to lose precious contents. The list is long.

Some studies and experiments can be months or years in the making. Halting a research project could mean losing large amounts of valuable data or millions of dollars in reagents. Some experiments would be impossible to reproduce because they involved, for example, unique biological samples that are no longer available.

“Put that in terms of people and careers,” explains Justus. “A postdoc, for example, that has spent the past two years of his or her life working on what might be ground-breaking research and who is now interviewing for an academic position somewhere, suddenly has to start over and the position has vaporized. We had several cases like that, with junior faculty, postdocs and students—all of whom lost some ground in their careers.”

Research leadership discussed whether it was reasonable to continue critical research and how to define it. Hector Wong, MD, then interim Director of the Research Foundation agreed that some research was critical: those studies that could adversely affect study participants and those studies that could not be reasonably reproduced, along with new investigations specific to the pandemic.

RULE ONE: KEEP EVERYONE SAFE

RULE TWO: STAY READY TO RE-START QUICKLY

In just four hours, Research Operations had created a detailed plan that protected our researchers and our research, and catalogued “what if” scenarios for a shutdown of an unspecified length of time.

Then the team set about inventorying, prioritizing, and tagging more than 100 liquid nitrogen units; updating contacts for hundreds of alarms; working with Praxair, FedEx and other vendors to understand delivery options; securing hazardous chemicals in labs; coordinating chemical waste disposal and biohazardous waste pickups; planning extra monitoring for “special needs” areas including sensitive cell cultures, crucial deliveries, and small labs lacking sufficient personnel.

Importantly, we requested (per Rule Two) labs not destroy biological lines that they would need on start up. We created a list of employees with experience in PCR, cell and tissue culture, animal husbandry, etc., to be able to mobilize resources if needs arose.

By far, our most significant contribution was the creation of effective communication channels. We compiled contact information for 520 essential staff members (ESMs) to serve as a “first line of defense” team. The Research Ops team is small; the ESM list was our multiplier and would become our eyes and ears.

ESMs were to come in for a couple of hours a week to maintain their area in a “ready state.” Ryan and Laura repurposed what had been the “Lab Managers Communications Website” (LMCW) as the primary two-way communication with ESMs, effectively providing real time information across all labs. We used our Research Ops email list for

lesser issues. We gave out our personal cell phone numbers to all, for any urgent issues that arose.

Ryan—well connected to the internal communications group—created the CenterLink structure for general broadcasts of COVID-related posts for research. To that, he posted templates and checklists provided by users for users, along with SOPs and guidelines developed by Research Ops, Shared Facility directors and others.

“We understood what was at risk. We felt every investigator’s anxiety,” Varney says “Everything had to be checked and re-checked to ensure messages were correct, clear, and consistent.”

On March 30th, we did final checks and lab walk-throughs and closed every lab door.

THE SHUTDOWN LASTED SIX WEEKS

Justus is a member of the medical center’s Emergency Operations group, led by Nathan Timm, MD, and Amber Antoni, MSN, RN. Daily Emergency Ops meetings enabled bi-directional flow of information between the research enterprise and the hospital, kept our messages congruent across the institution, and allowed Research Ops to pivot instantaneously. After every 90-minute meeting, Justus relayed information to Ryan, Danny and Laura (and others as needed). The Research Ops team then engaged accordingly.

Throughout the shutdown, hospital care teams continued to care for patients. The Research Ops team assisted when they could. For example, using new communication channels, we solicited for and collected PPE, reagents for developing PCR tests, swabs, and other items.

“Our research colleagues were just as eager to help and their responses to solicitations were impressive,” Justus says. “We provided equipment, expertise and space for decontaminating an initially limited supply of N95 respirators. Thanks to our freezer update program, we had new freezers on-site and were able to provide ample cold storage for COVID-19 vaccines when freezers were backordered by every vendor in the wider marketplace.”

The Office for Clinical and Translational Research (OCTR) and the Schubert Research Clinic developed methods to facilitate—as much as possible—remote clinical research studies. For those studies not amenable to remote work but critical to continue, they worked to ensure protocols aligned with hospital practices.

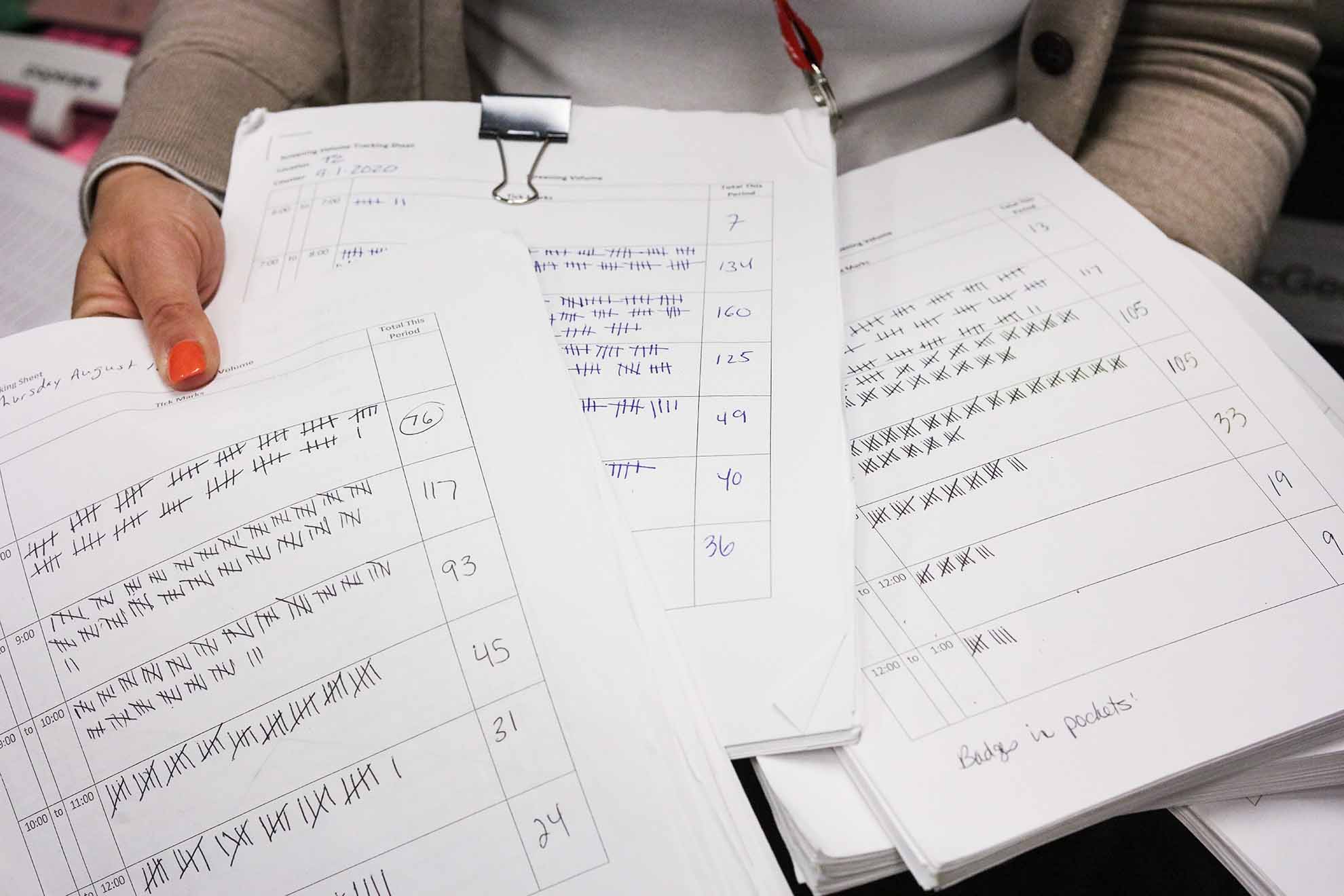

Although only a fraction of research employees was on campus, Laura set up a volunteer sign-up system and screening stations for research. This mirrored procedures at other clinical locations but every shift was run entirely by volunteers.

About half our Shared Facilities (primarily those that provided clinical services or were necessary to maintain critical research) remained open throughout the shutdown. Shared Facility directors adapted on the fly, writing new sanitizing procedures, maintaining glass-wash services needed by labs doing critical COVID-related experiments, relocating large instruments to isolated areas, and innovating ways to train or troubleshoot. Our vivarium staff reduced services to only core animal husbandry, but we never needed to resort to large-scale reductions in biomass.

More than once, Research Ops activated their “what if” plans. The freezer monitoring systems went down on several occasions: Danny hosted vendor technicians to repair it. Freezers failed: essential personnel were called in and Danny supplied a backup to transfer samples. Laura worked with Supply Chain to re-route deliveries containing dry ice until lab personnel could tend to them.

The team remedied vendor issues, access issues, purchasing issues, delivery issues, connectivity issues, and more. In a typical week, between March of 2020 through January of 2021, the three-person team received as many as a dozen texts per week about urgent issues.

“I feel like we were juggling so many things at once that we didn’t even realize how much we were actually doing,” recalls Runck. “We all felt like there was a lot at stake and we couldn’t let anyone down.”

One of the most difficult issues was an HVAC repair requiring the entirety of Location S be taken off-line for an extended period of time, presenting a dangerous scenario. The lack of air movement for 48 hours meant that hundreds of freezers were at risk for overheating and massive losses of unique biological materials. It also provided a real possibility of toxic or flammable fumes building up in small lab spaces.

In preparation, we re-checked every lab and worked with Protective Services to maintain security and a state of readiness with the Cincinnati Fire Department. Impressively, Plant Engineering completed the fix in just over 36 hours, without event.

A FRENZIED RESTART

The Governor lifted the Stay-at-Home order on May 1. However, firing up the research engine was difficult because it occurred while the pandemic was still raging. Had the virus cleared entirely, we would not have been concerned about PPE and social distancing, and operations could have returned immediately to business as usual. But it was not business as usual.

Keeping everyone safe (Rule One) meant limiting the number of people on campus long after the restart. The limited number of people on campus had major effects on every partner to Research Ops: Food Services, Environmental Services, Parking & Transportation, Plant Engineering, Supply Chain, Protective Services, etc.

“We believed that the only real way to restart was to get input from each of our investigators about what they needed so that we could give our partners good information about required resources,” Justus says. “We collected Investigators’ Ramp-up Plans, analyzed them within days, and the research engines started to rev on May 11.”

The resulting activity was substantial and frenetic. We contacted users and remedied out-of-date service records on fume hoods and biosafety cabinets. We sourced items pertinent to safety and a means to distribute them: alcohol, spray bottles and wipes for decontaminating equipment and surfaces, along with hand sanitizers in high traffic areas (at a time when hand sanitizer hard to obtain!).

Signage—both paper and digital—was posted with information about entrances, masking, distancing, and other particulars. We monitored the numbers of employees coming through screening stations. With Jason Luthy, of Design, Construction & Space Planning, we reviewed seating areas, and looked at alternatives to maintain social distancing as more people came back to campus.

The first research areas to fully come back online were the Shared Facilities, and each of the directors were thorough in assessing needs and creating new SOPs. The team also worked with many others to get appropriate SOPs in place.

For example, with Steve Waggoner, PhD, chair of the Institutional Biosafety Committee, we created new protocols for working with human samples that could harbor SARS-CoV-2. Michelle Adams, PhD, Rebecca Harper, DNP, and Jareen Meinzen-Derr, PhD, MPH, developed models for clinical research (e.g., remote, on-site, group sessions, home studies) and what precautions or restrictions were necessary.

Again and again, our communication channels functioned as a significant conduit during the progression of the pandemic. With every new piece of information about the virus and testing and (ultimately) vaccines, came multiple adjustments in logistics and operations for the various types of research performed here.

As weeks and months progressed, we adjusted. Screening stations ceased; new practices were deployed. We continued to work with Purchasing to obtain essential materials. Researchers adopted the LMCW to request/donate/share reagents that were unavailable from commercial suppliers.

We worked with Plant Engineering and Materials Management to install masking stations and hand sanitizers. We worked with Bob Baer to stay abreast of parking and shuttle services. Through it all, we learned a great deal.

“We believe we were one of the first research organizations in the country to reopen, and to that end we were successful with Rule Two. Not a single case of COVID-19 was traced back to infection within the research complex—success with Rule One,” Justus says. “I am proud of what our team accomplished. In addition to the Ops team, many people contributed to Cincinnati Children’s successes over the past year and a half. We are grateful to each and every one of our partners across this wonderful organization.”

Respect. Truth. Team. Impact.

Related Posts:

Cincinnati Children’s Plays Central Role in COVID-19 Vaccine Clinical Trials

Mitigating the Mental Health Burden of COVID-19

Contributing to COVID Knowledge

Studying the Heart in the Storm

Pandemic Prompts Dash to Build Dashboards

Exploring Intersections Between COVID-19 and Co-Morbidities

Balancing COVID Safety and Learning Needs

Anderson Center Team RACEs to Respond to COVID

Explore the full 2021 Research Annual Report

50+ Discoveries and Innovations (Enter Research Area, click on “Featured Research”)

By-the-Numbers Section Breaks Down $270M+ in Funding

Learn About Science Careers and Student Opportunities

Find Out How You Can Support Research at Cincinnati Children’s