For Children After Stem Cell Transplants, Food Timing Matters

Research By: YunZu Michele Wang, MD | Christopher Dandoy, MD, MSc | John Hogenesch, PhD

Post Date: February 15, 2023 | Publish Date: Feb. 15, 2023

Daytime-only feeding schedule may reduce hospital length of stay vs. continuous feeding, according to experts at Cincinnati Children’s

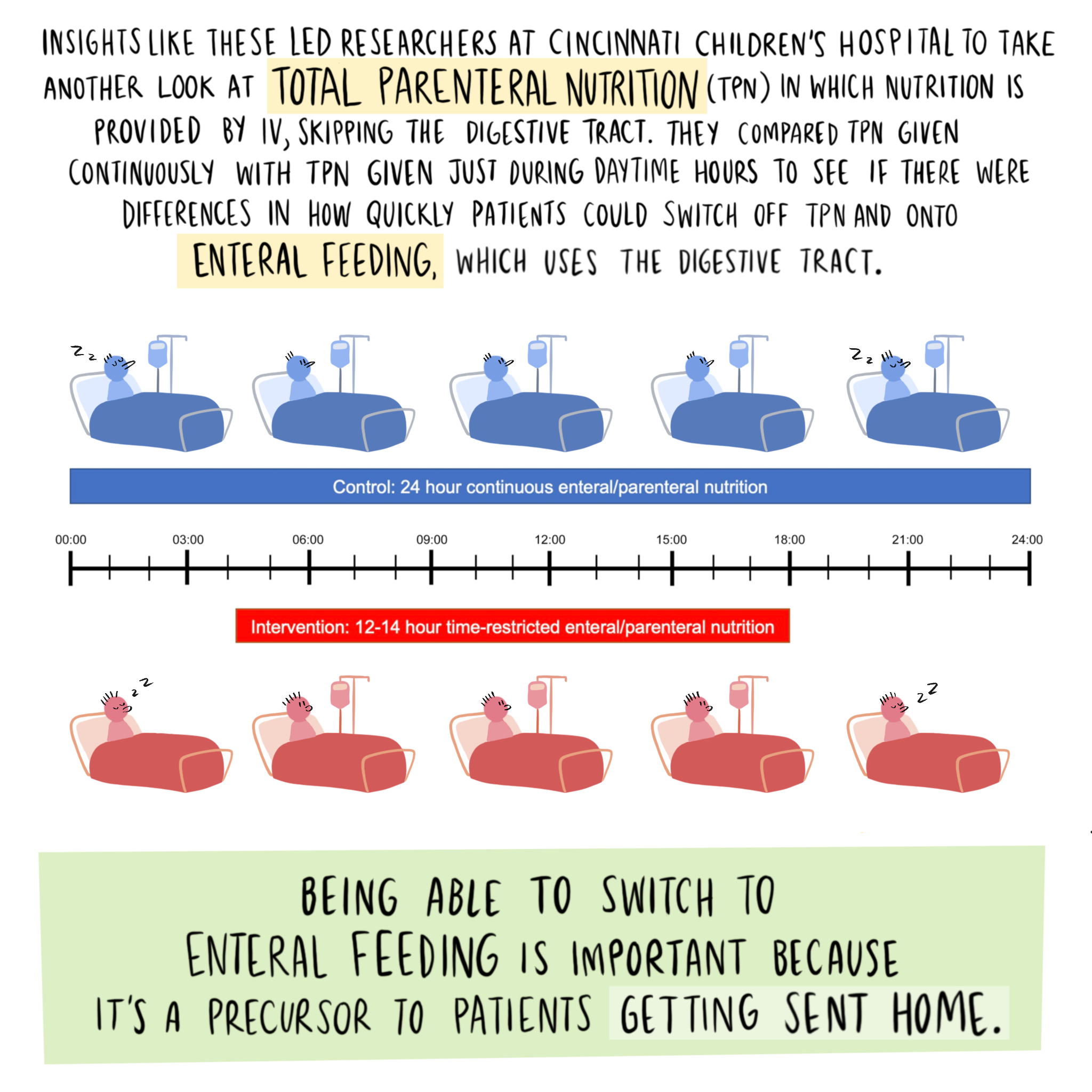

While children are recovering in the hospital after receiving a stem cell transplant to treat leukemia or other rare blood diseases, most are not in a condition to eat solid food. So instead, these children receive liquid nutrition through an IV that runs nearly 24-hours-a-day for several weeks.

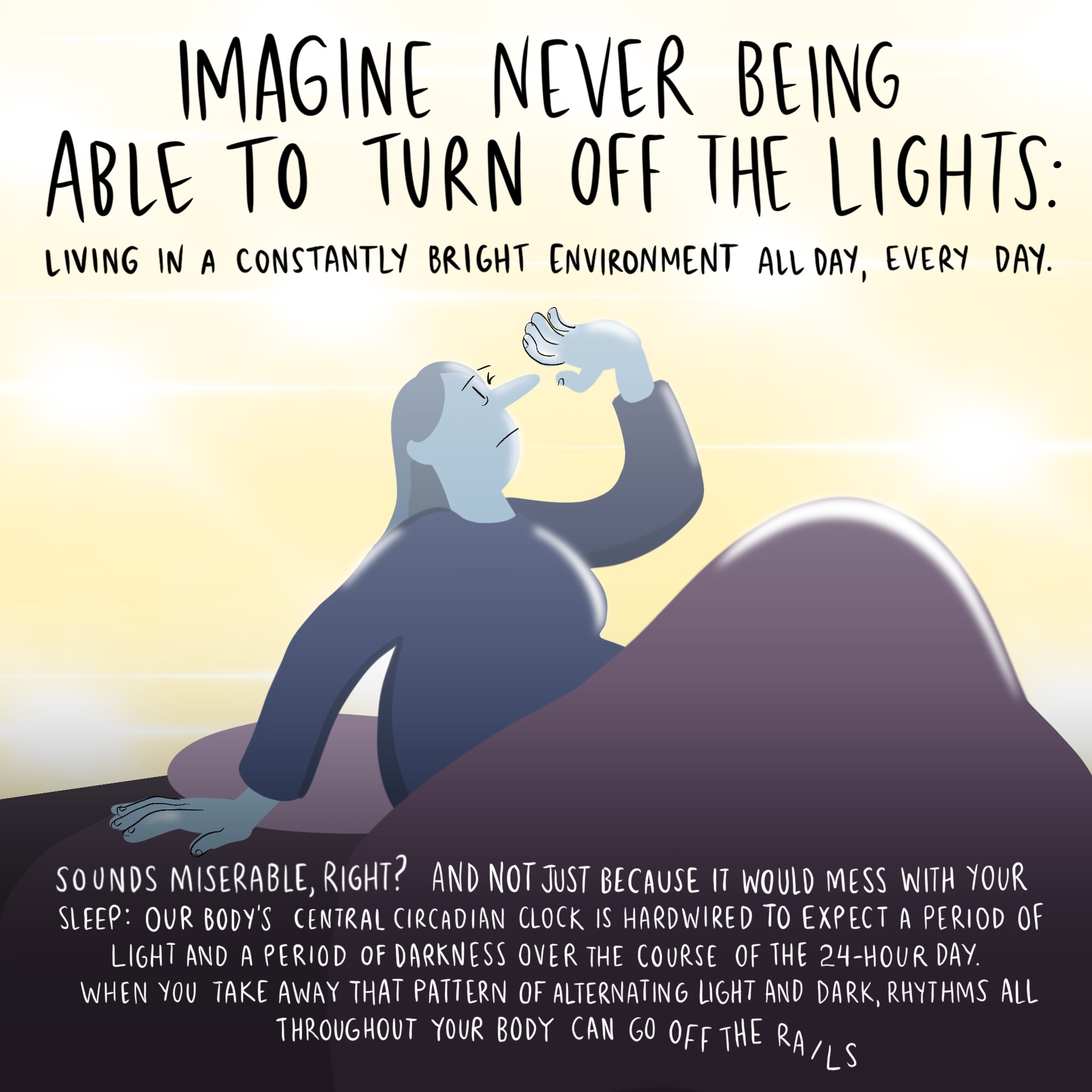

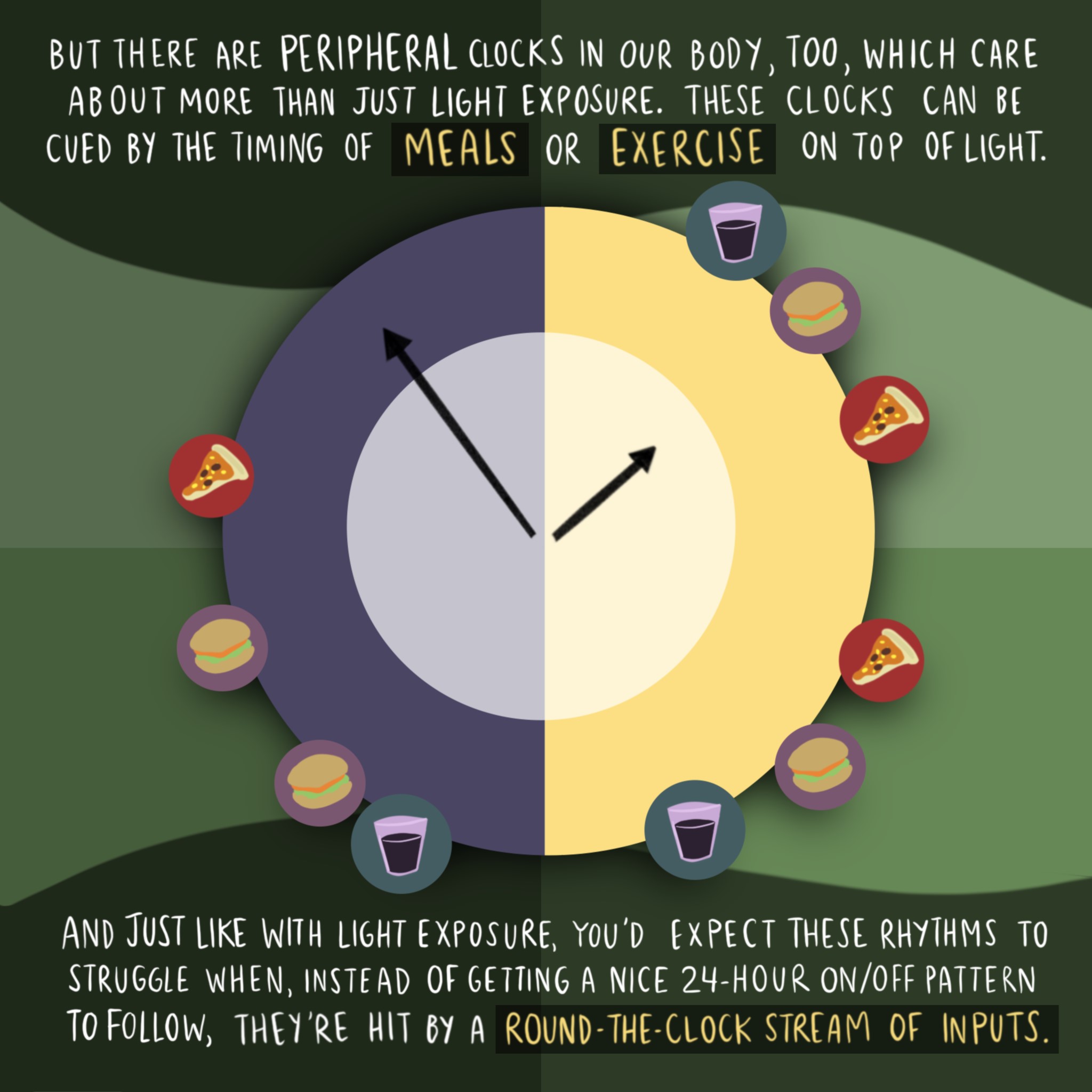

Previous studies already have shown that feeding at night plays havoc with metabolism, potentially leading to long-term risks for obesity, diabetes, hypertension, and other conditions. Now, experts in circadian medicine and cancer care at Cincinnati Children’s have demonstrated that recovering patients do better when feeding is restricted to daytime hours only.

Details were published Feb. 15, 2023, in the Journal of Clinical Investigation by first author YunZu Michele Wang, MD, Division of Bone Marrow Transplantation and Immune Deficiency, and several colleagues at Cincinnati Children’s. If the successes reported in this initial study can be replicated at other hospitals, children would need less time in the hospital and health care spending could be reduced.

“Children receiving time-restricted feeding appear to be quicker at transitioning to normal oral feeding. That’s a key milestone they need to achieve to go home,” says senior co-author John Hogenesch, PhD, a circadian biologist based in the Division of Human Genetics.

Small study suggests potential savings

The clinical trial involved 18 patients at Cincinnati Children’s, eight of whom received daytime-only feeding while the rest received traditional continuous feeding. All the patients received a full-day’s amount of calories.

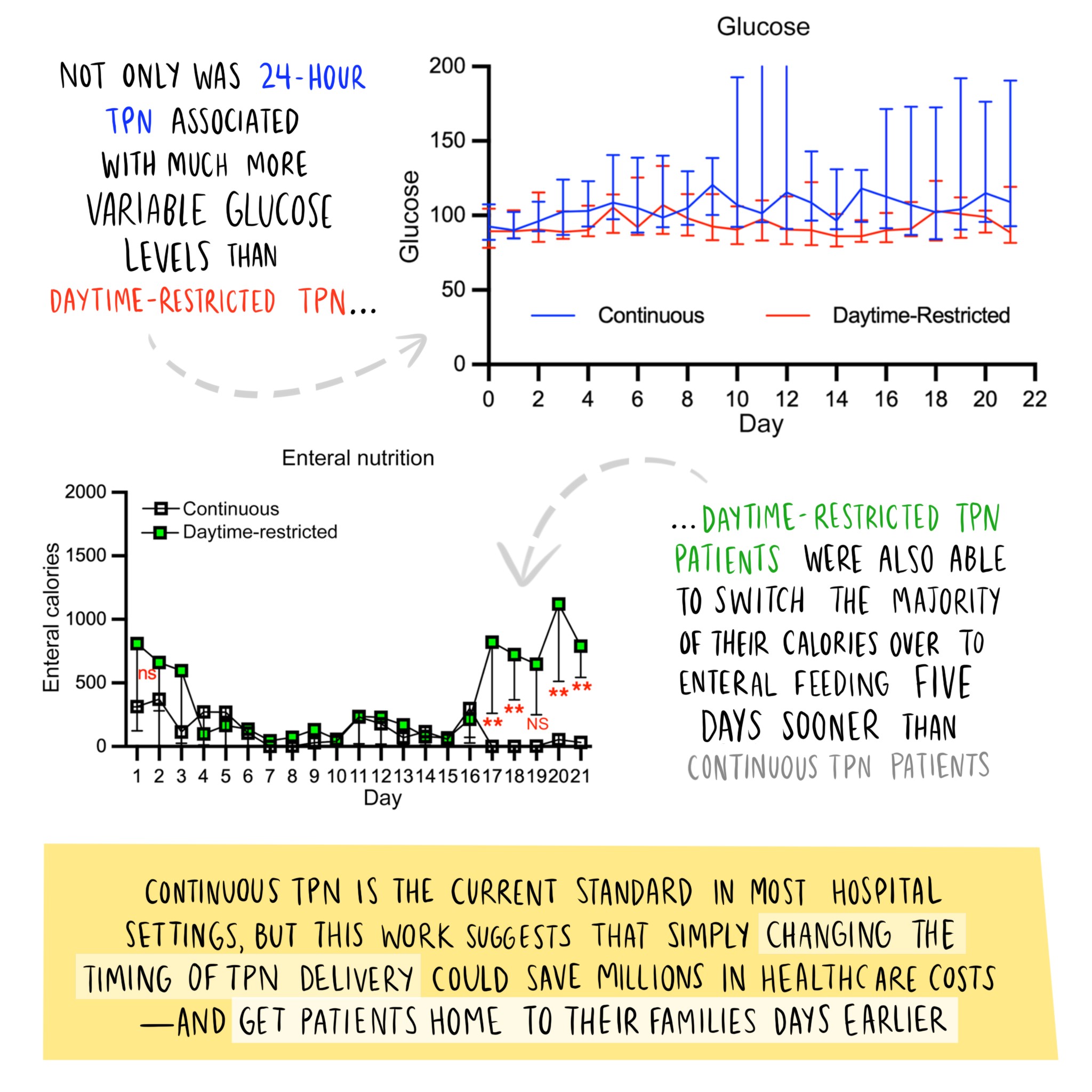

Overall, testing revealed sharply higher spikes in blood glucose levels among children receiving continuous feeding compared to daytime-only feeding. This reflects a circadian rhythm in human metabolism—our bodies tend to shut down glucose processing at night, Hogenesch says.

“Improved blood sugar control is important because as many as 30-50% of stem cell transplant recipients experience hyperglycemia (excess blood sugar) after their transplant, and this is associated with an increased risk of infection, need for extended intensive care, and other bad outcomes,” Wang says.

By three weeks after transplant, the patients receiving daytime-only feeding were eating more by mouth than those who received continuous feeding. While the study suggests that daytime-only feeding reduces the overall length of hospital stays, the number of participants was too small to draw a firm conclusion. A larger study would help control for other factors that can affect length of stay, such as transplant complications including infections or graft-versus-host disease, co-authors say.

More research may be worth the effort.

“The cost of staying in a bone marrow transplant ward can reach $15,000 a day,” Hogenesch says. “So, not only could these kids get home to their family and friends sooner, it could also save the US health system hundreds of millions a year.”

Next Steps

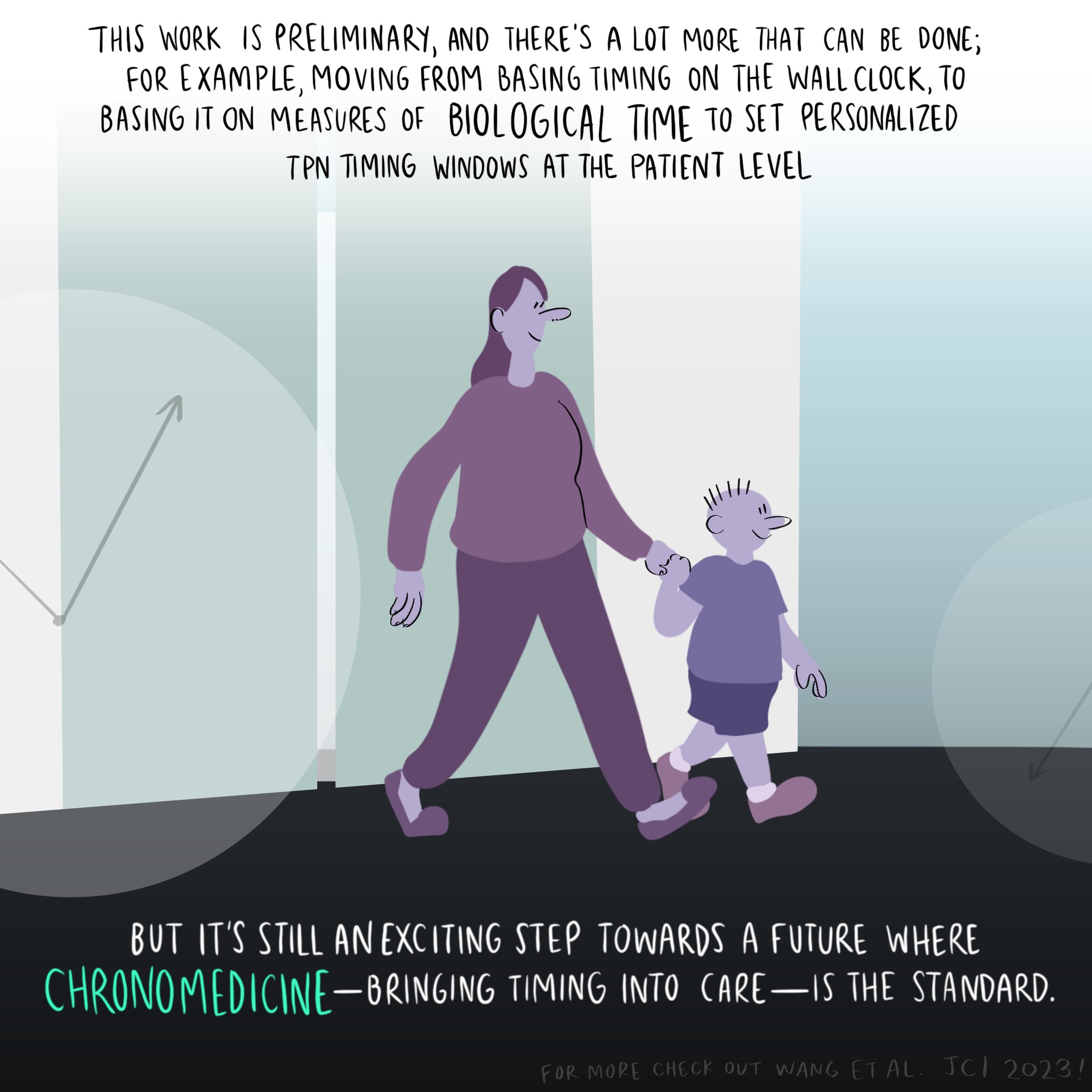

Wang and colleagues plan to open a larger study of daytime-only feeding for all conditions involving stem cell transplants at Cincinnati Children’s.

“If our findings are consistent in a larger group, we would then plan to develop a multi-site study in children and adults receiving stem cell transplants,” Wang says.

Meanwhile, senior co-author Christopher Dandoy, MD, MSc, and colleagues are continuing to evaluate hospital conditions that can prevent good sleep, which also appears to disrupt circadian rhythms and may slow recovery.

| Original title: | Daytime-restricted parenteral feeding is associated with earlier oral intake in children following stem cell transplant |

| Published in: | Journal of Clinical Investigation |

| Publish date: | Feb. 15, 2023 |

Research By

My two primary research areas of interest are in developing cellular therapies for hard-to-treat cancers and studying the role of the circadian rhythm in our transplant patients.

My research focuses on identifying, testing and implementing clinical strategies to help improve outcomes after stem cell transplantation for malignancy.

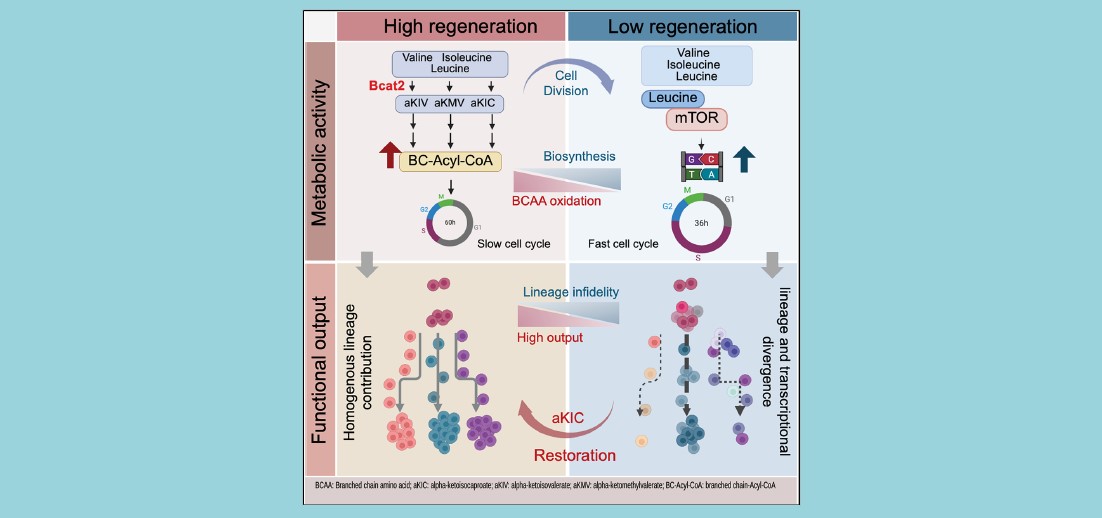

The Hogenesch lab studies transcriptional outputs of the clock in animal models and humans.