A New Look at Immunity in Newborn Infants

Research By: Sing Sing Way, MD, PhD

Post Date: June 26, 2019 | Publish Date: Nov. 6, 2013

No wonder babies cry.

These tiny, fragile people arrive abruptly – delivered from the dark and protective environment of their mother’s womb to a big, scary world of light and noise.

If this is not intimidating enough, newborns also face a long receiving line of microbes eagerly awaiting a new home. Of course, all of this happens while their developing immune systems are exceptionally vulnerable to various onslaughts from the outside world.

Infants’ vulnerability to infections has been well known for a long time. Now, research from Cincinnati Children’s reported in the journal Nature offers a new explanation for why, and an idea about how we might make babies more resilient to harmful infections.

The study comes from a team of scientists led by Sing Sing Way, MD, PhD, a pediatrician in the Division of Infectious Diseases and the Perinatal Institute. Way knows the territory well. He is often called in to help manage infectious complications among newborn infants at Cincinnati Children’s. He also spends considerable time in the laboratory looking for ways to improve immune function in this highly vulnerable population.

HOW ACTIVE SUPPRESSION HELPS COMMENSAL BACTERIA TAKE ROOT

Prior to this study, the prevailing view was that newborns are susceptible to infection during the first few weeks of life because the cells that make up their immune system are immature or underdeveloped. But Way and his colleagues found that cells programmed to allow helpful bacteria to colonize the intestines of newborns also suppress the baby’s immune system – making babies more vulnerable to infection.

“The first few days after birth represent a critical developmental period when a baby’s immune system must adapt and discriminate between friendly microbes and those that may cause more serious infection,” he says.

These include environmental “commensal” microbes that are not present in the womb, but that immediately colonize tissues such as the intestine and skin, Way explains. “Our findings fundamentally change how we look at why neonates are susceptible to infection. They suggest that susceptibility is caused by active immune suppression during this developmental period, as opposed to immaturity of immune cells.”

BLUNTED IMMUNITY IS PART OF THE PLAN

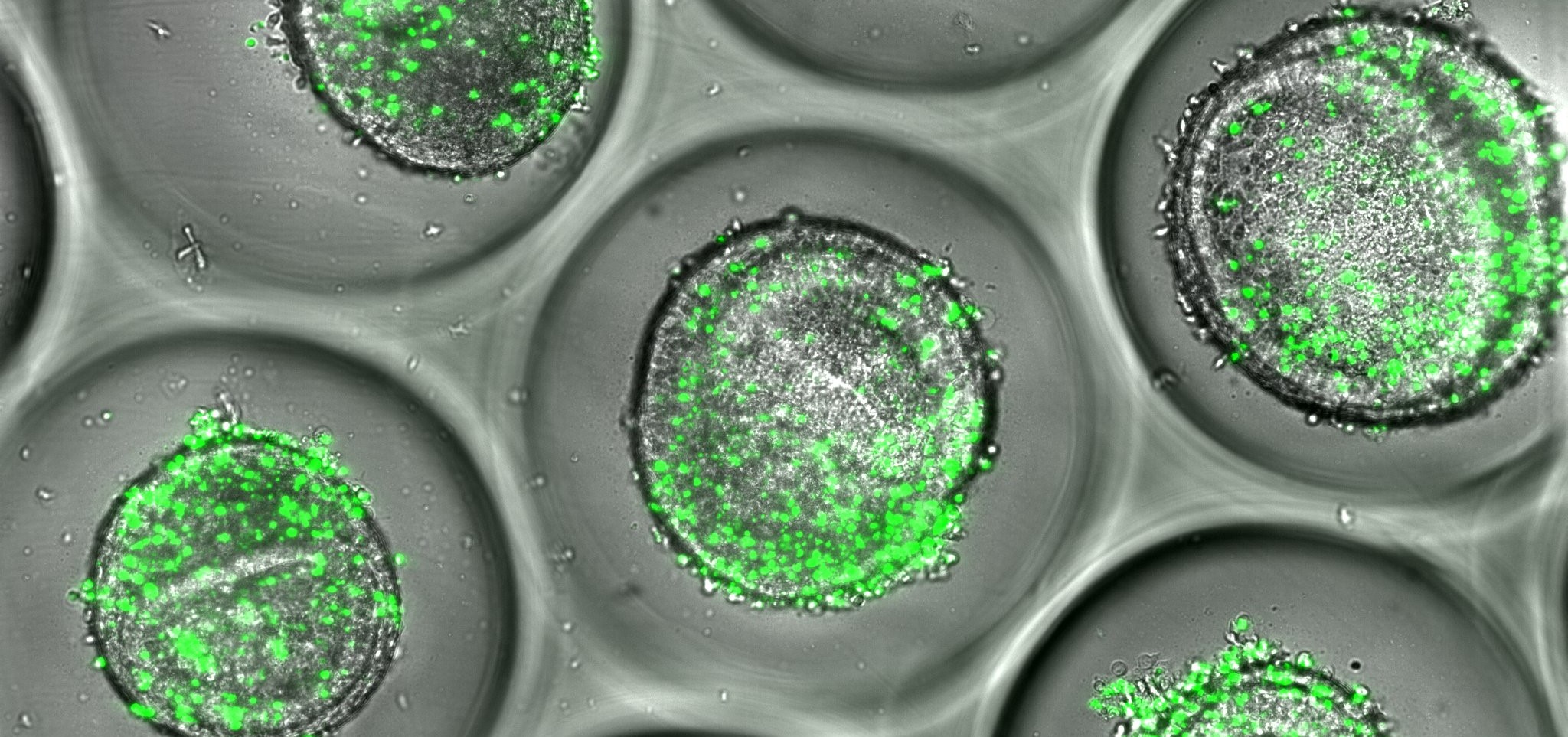

Way says the finding could prompt a major shift in how pediatricians and scientists deal with the threat of neonatal infections – and in particular how researchers go about looking for ways to control or stop it. The study points to cells that suppress immune responsiveness in newborn infants. The suppressive cells in this case are CD71+ erythroid cells, precursors of mature red blood cells.

The researchers found that the cells are highly enriched in newborn mice and humans to prevent an over-reactive immune response as infants adapt to their new, microbe-filled world. Neonatal CD71+ cells express an enzyme called arginase-2, essential for its immune suppressive properties. This plays a vital role in infants’ developing intestines by preventing an onslaught of inflammation in response to colonizing bacteria that help digestion and absorption of nutrients.

His research team used a series of laboratory tests in human neonatal cord blood cells and complementary infection studies in newborn mice to show that temporary immune suppression in neonates extends beyond the intestines into other parts of the body. Way and his colleagues started their study because earlier laboratory research showed the degree of compromised immunity in infant mice varies significantly depending on specific experimental conditions. This prompted the authors to hypothesize that there must be another reason for compromised immunity in neonates, other than just immature immune cells.

CELL SWAPPING PROVES THEORY

The scientists transferred immune system cells in bulk from adult mice into newborn mice. They wanted to see if this would boost neonatal immunity when exposed to infection. Instead of enhancing immunity, researchers say the production of protective immune system cytokines among adult cells remained blunted in newborn mice. Similar results were observed when adult immune cells were mixed with neonatal cells in laboratory cultures.

In a complementary experiment, researchers transferred neonatal immune system cells into adult mice exposed to infection. The neonatal cells produced the protective cytokine TNF-alpha, which helps ramp up the immune system’s protective response against infection.

BENEFITS OF IMMUNE SUPPRESSION OUTWEIGH RISKS

Way says the benefits of immune suppression by neonatal CD71+ cells are more uniformly advantageous by quenching undesired inflammation with commensal microbial colonization. On a population level, this probably outweighs the threat of infection among individual infants. He also stresses the importance of follow up studies to develop ways to protect newborns from systemic invasive infections, while still allowing CD71+ cells to do their job preventing inflammation in the developing intestine.

The goal, he explains, is to find a way to help nature achieve and maintain the right balance of immune stimulation required for optimal protection against infection and immune suppression to prevent immune cell mediated damage.

“Having identified the importance of immune suppression and the unique cells and molecules whereby this is achieved in neonates, our goals now are to try and dissociate the harmful impacts of immune suppression that cause infection susceptibility from their more universal beneficial roles to avert overwhelming inflammation during the transition from the womb into a more hostile external environment.

Learn more about the research happening at our Perinatal Institute

—By Nick Miller

(This article originally appeared in the Winter 2014 issue of Research Horizons)

| Original title: | Immunosuppressive CD71+ erythroid cells compromise neonatal host defence against infection |

| Published in: | Nature |

| Publish date: | Nov. 6, 2013 |

Research By