Understanding COVID-19 Transmission

Post Date: February 15, 2021 | Publish Date:

“Household contacts are six times as likely to lead to a transmission event as other kinds of contacts.”

—Justin Lessler, Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health.

On Feb. 10, 2021, Justin Lessler described how to merge evidence from COVID-19 contact tracing studies and population level trends to gain a full picture of viral transmission.

Lessler presented “Understanding COVID-19 transmission: from households to populations” during the third installment of the Current Topics in COVID-19 Research Seminar Series (click here to watch the recording). Hosted by the Cincinnati Children’s Divisions of Infectious Diseases and Biostatistics & Epidemiology, these free virtual seminars feature discussions with cross-disciplinary research professionals on the latest COVID-19 information and science.

Lessler is an associate professor of epidemiology at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and a member of the Johns Hopkins Infectious Disease Dynamics Group. The main focus of his research is to better understand and control infectious diseases through the development and use of statistics, dynamic models, and novel study designs.

Measuring Transmission

Lessler reviewed the various ways to measure viral transmission, including:

- Risk-ratio of infection: The relative risk of infection in certain exposure classes.

- Household Secondary Attack Rate: The number of secondary infections after a pathogen is introduced into a household.

- Reproductive Number (R): The number of cases we expect a single infectious individual to infect, given the current conditions. This gives us a sense of the scale of the epidemic, the thresholds of herd immunity, how it will grow, and what we have to do to control the disease.

- Basic Reproductive Number (R0): The reproductive number at the start of an epidemic.

He shared evidence from recent COVID-19 contact tracing studies that found that people will most likely be infected by a known individual rather than those they may run into in the community.

“Household contacts are six times as likely to lead to a transmission event as other kinds of contacts,” he said.

When describing some of the advantages and shortcomings of contact tracing studies, he revealed that they can be valuable early in an epidemic to quickly identify individuals at risk and prevent transmission. However, they generally focus on symptomatic cases, and a high proportion of COVID-19 cases are asymptomatic.

Lessler confirmed that household serologic surveys, conducted late in an epidemic wave, are an especially useful study design for understanding transmission and capturing asymptomatic transmission.

“In most cases, it gives more complete data on total attack rates than virologic or symptomatic information because you’ll catch those asymptomatic people,” Lessler noted. “You won’t have necessarily the same response bias because you can do it as a population survey.”

However, there are potential problems with these types of studies—the immunologic response may be heterogenous and there won’t be temporal information.

“Since you’re doing the study in the future, you may have problems with recall bias,” he revealed.

Using chain binomial models, Lessler and his research colleagues analyzed data collected from serosurveys that were conducted in Geneva, Switzerland after the first wave of infection. They found that the overall probability of being infected outside of the household was about 5% over the course of the entire wave. However, people who were exposed to an infected member of their household had a 17% chance of being infected.

Overall, Lessler and his colleagues were able to show that those reporting symptoms were approximately three times more likely to infect another household member compared to those who did not report having symptoms.

Risks Associated with Reopening Schools

Lessler shared research demonstrating that young children are less susceptible to contracting COVID-19 than adolescents and adults. However, he reminded viewers that understanding the risks for reopening schools involves more than just transmission within the classroom.

“When schools are open, it’s not just the kids getting infected in the schools that we worry about,” he said. “It’s the fact that schools connect communities.”

It is necessary to consider the effects on transmission for the entire network that is reopened, such as bus transportation, extracurricular activities, changes to parents’ schedules, and more.

He confirmed that, in general, schools have not been associated with huge outbreaks overall and have had multiple intervention measures in place, such as student and teacher masking, reduced class size, restricted entry, daily symptom screenings, desk shields, extra space, and more.

“These are a suite of interventions,” he noted. “You’re rarely seeing one of these interventions alone.”

Lessler posed a question to the viewers: “We can say that school closure is associated with reduced transmission, but is that causation or association?” he asked.

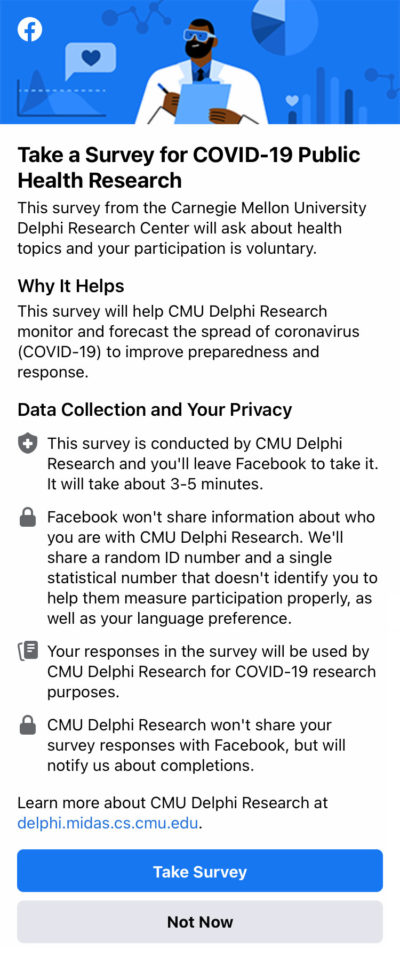

To answer this, he and his colleagues used data collected from the Carnegie Mellon Facebook COVID-19 Survey—a voluntary survey that asks about health topics, COVID-19 symptoms, and schooling experience of any children in the household. Each week, it draws approximately 500,000 survey responses from U.S. adults aged 18 and older.

To date, more than 650,000 respondents have reported a school aged child. Data from this survey found that individuals with school-aged children attending in-person schools were experiencing more COVID-19 outcomes than individuals without children.

“It’s a helpful suggestion that in-person schools do pose a risk,” he said. “But, mitigation to households with school-aged children attending in-person schools can be reduced. That doesn’t mean I think that opening schools can’t have other effects because of how they connect up through communities.”

His view of the evidence he shared is that opening schools with inadequate intervention measures has a high factor for risk.

“You have to have measures in place to safely open schools,” he said. “Once you have a sensible number of intervention measures in place, you can rapidly bring things under control and make schools safe.”

Watch a recording of the entire seminar.

WHAT’S NEXT?

Next up in the Current Topics in COVID-19 Research Seminar Series: Denise J. Jamieson, MD, MPH, James Robert McCord Professor and Chair of Emory University’s Department of Gynecology & Obstetrics.

Jamieson will present “Pregnancy in the time of COVID-19” and provide updates on what is known about COVID-19 in pregnancy, including clinical course and severity, birth outcomes, and risks of perinatal and breastfeeding transmission. Her presentation will also highlight the latest developments on COVID-19 vaccinations for pregnant and lactating women.

Join this free virtual seminar at 2 pm (ET) March 10, 2021, via Zoom.