The Joy of Witnessing Science Transform a Life

Post Date: November 15, 2024 | Publish Date:

Promising gene therapy appears to conquer the rare disease AADC deficiency

Sriansh Ojha was fully into his “terrible twos” on an April afternoon at Cincinnati Children’s as he squealed and chased his older sister around the sunlit lobby of the Schubert Research Clinic.

Urging the laughing little boy to slow down was a parenting task that his mother, Bhawana Dhakal, and father, Tirtha Raj Ojha, of Lexington, Ky., felt profoundly pleased to perform. That’s because in the first year of life, their son struggled to eat, could not lift his head off the bed, could not control his eye movements, and was not expected to ever be able to walk, much less run.

“Gene therapy is a blessing I must say. You can see my child, before and after, and see that it works. He’s a new person. He has a new life,” Bhawana says.

Sriansh was born with a rare genetic condition called AADC deficiency. In November 2022, at age 16 months, Sriansh became the youngest child in the world to receive a remarkably successful one-time gene therapy made by New Jersey-based PTC Therapeutics Inc. The treatment is now being marketed under the brand name KEBILIDI™.

Sriansh, now 3 years old, was part of a clinical trial that led the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to grant accelerated approval of the treatment on Nov. 13, 2024. The new treatment represents the first gene therapy approved in the United States that is directly administered to the brain. (Read the PTC media release)

The therapy was developed about 15 years ago in Taiwan. Since 2010, when the first patient was treated, the therapy was tested and then approved in 2023 for commercial use by the European Union, the United Kingdom, and Israel. So far, only about 30 children worldwide have received the treatment.

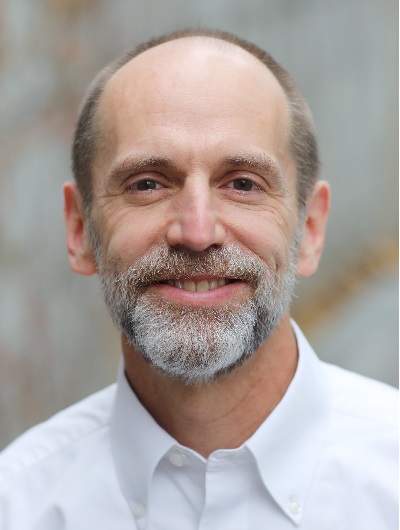

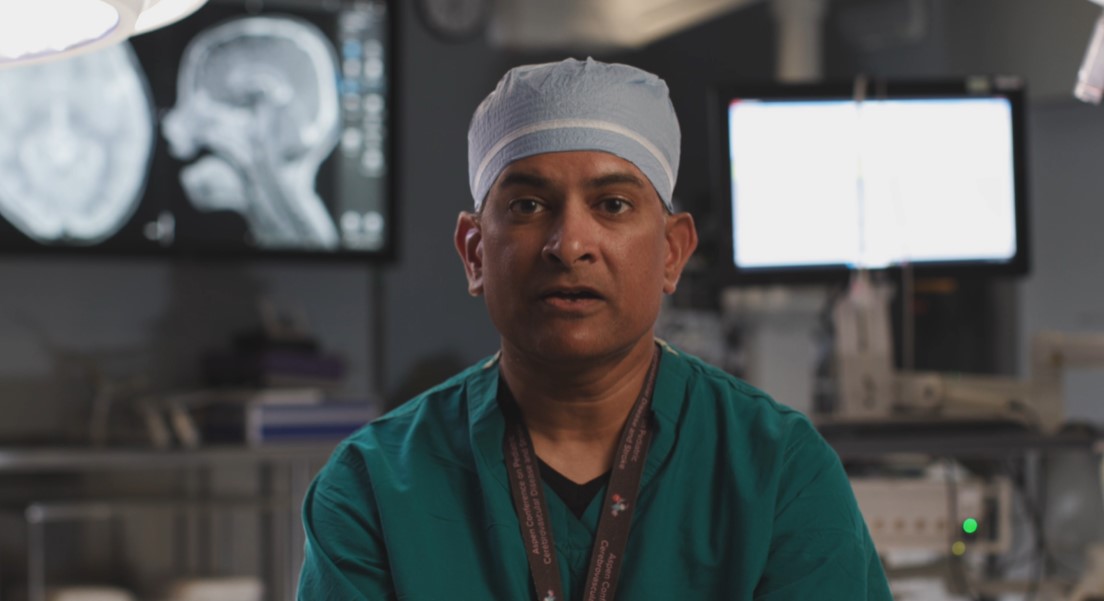

Donald Gilbert, MD, MS, a movement disorder expert with the Division of Neurology at Cincinnati Children’s, played a central role in treating Sriansh and enrolling him the clinical trial.

He saw, in full clinical detail, exactly how severe Sriansh’s condition was before the therapy. Then he saw Sriansh for a follow-up visit three months after a high-tech surgical procedure delivered the gene therapy to his brain.

“When I walked in and saw him, sitting up, completely on his own…” Gilbert pauses for a moment. “I will never forget that.”

“The way that a missing gene can be put in the brain in the place where it’s needed, in a single-day treatment, and then produce what is needed for the rest of a child’s life is amazing,” he says.

What is AADC deficiency?

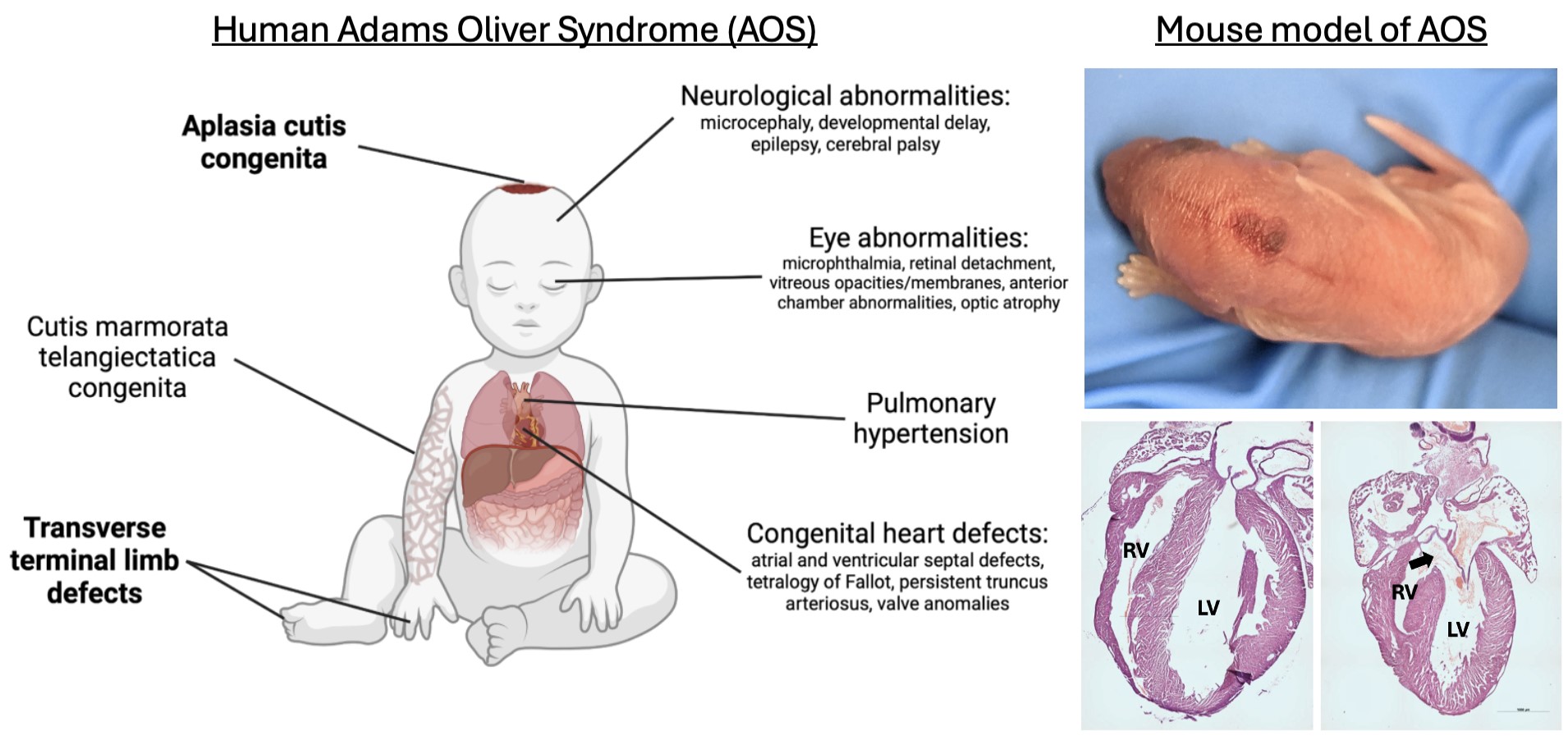

Aromatic l-amino acid decarboxylase (AADC) deficiency is a very rare inherited genetic disorder that disrupts how signals pass among nerve cells in the brain and beyond. Specifically, mutations in the gene DDC produce a damaged version of an enzyme called AADC, which is needed to produce dopamine and serotonin. Without adequate amounts of these neurotransmitters, the brain, spinal cord and peripheral nerves cannot properly function.

Unusual problems begin appearing within months of birth and get worse. Symptoms include muscle weakness, unusual eye rolling, involuntary writhing movements, stiffening, and irritability. Affected infants often feed poorly, sleep badly and startle easily.

In October 2021, when Sriansh was about three months old, his grandfather was the first to notice that Srinash was having difficulties.

“He had eye deviations, an arching back, and he used to sleep a lot. He was only awake like one or two hours and then would go back to sleep,” Bhawana says. “Later, his aunt and a neighbor also said there is something wrong with Sriansh because normally kids don’t twist their hand and arm the way he did.”

Chasing down the diagnosis

Bhawana emigrated from Nepal to Los Angeles in 2013 with her parents and brother. She and Tirtha were married in Nepal in 2014, then the family moved to Lexington in 2016.

Their first child was born healthy. So neither parent had any idea they were carrying rare variations in the same gene. Then they each passed along a copy of that gene variant to Sriansh, a variant that virtually no medical center looks for during prenatal testing for a condition that shows no signs during routine ultrasound exams.

In fact, many neurological conditions can cause some of the symptoms Sriansh experienced. In general, clinicians look for the most common possible conditions before suspecting the extremely rare.

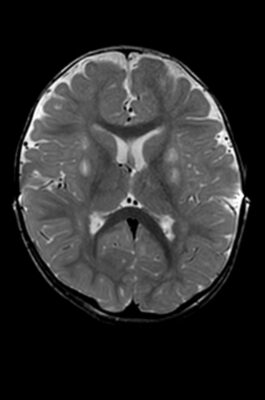

In Kentucky, several physicians worked to figure out what Sriansh had. The family took Sriansh to hospital admissions, EEG tests, MRI scans, and spinal taps to rule out seizure diseases and other possibilities. One doctor recommended travelling to a dystonia expert in New York.

Eventually a complete genome test was ordered. But the family was told that processing the results would take three months. While waiting, Tirtha and Bhawana dove into online research and received various recommendations from far-flung friends and relatives.

The searching suggested that Cincinnati Children’s, about 100 miles north of the family’s home, had considerable expertise treating dystonia and other rare neurological disorders. So, when Sriansh started showing even more severe symptoms, the family made the drive.

Sriansh was admitted for a stay that lasted nine days. During that admission, results came back from the genome test: Sriansh had the rare, severely disabling disease “Amino Acid Decarboxylase Deficiency.” The rest of Sriansh’s life was expected to involve treatment of his neurological symptoms, with at most limited benefit. The care team prepared the family for the implications of Sriansh facing a lifetime of 24/7 home care and countless more visits to medical offices and hospitals.

But in this case, there was another option, available in only four centers in the United States.

“I knew about a little bit about gene therapy. Back home I knew about a family that was raising money to get gene therapy for another rare disease,” Tirtha says. “So, when Dr. Gilbert suggested gene therapy for Sriansh, I said, ‘Of course, yes.’”

Science fiction becomes reality

For many years in medicine, gene therapy has been something that was coming someday. Under development. Just around the corner. For the Ojha family, the future arrived on Nov. 15, 2022.

Delivering this gene therapy required advanced technologies and a team of experts in neurosurgery and anesthesia.

Since 2007, Paul Wuh-Liang Hwu, MD, PhD, and colleagues at National Taiwan University Hospital worked to develop the treatment. The current approach involves attaching a healthy version of the DDC gene to a modified virus called AAV9. The procedure calls for injecting more than 1 billion of these engineered viral vectors directly into the brain—specifically into the putamen, a small round structure deep in the brain that plays a vital role in motor control, speech articulation, cognitive function and more.

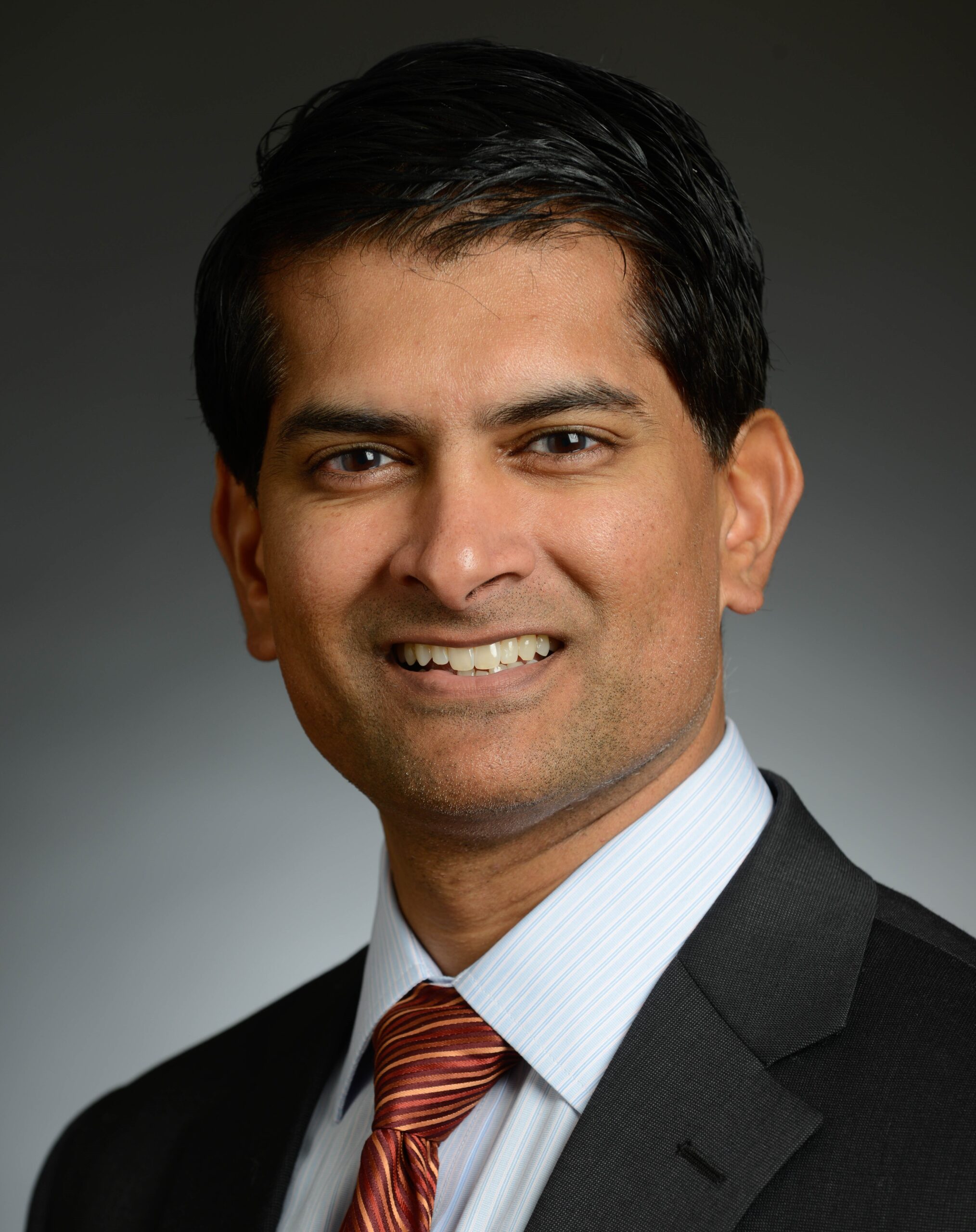

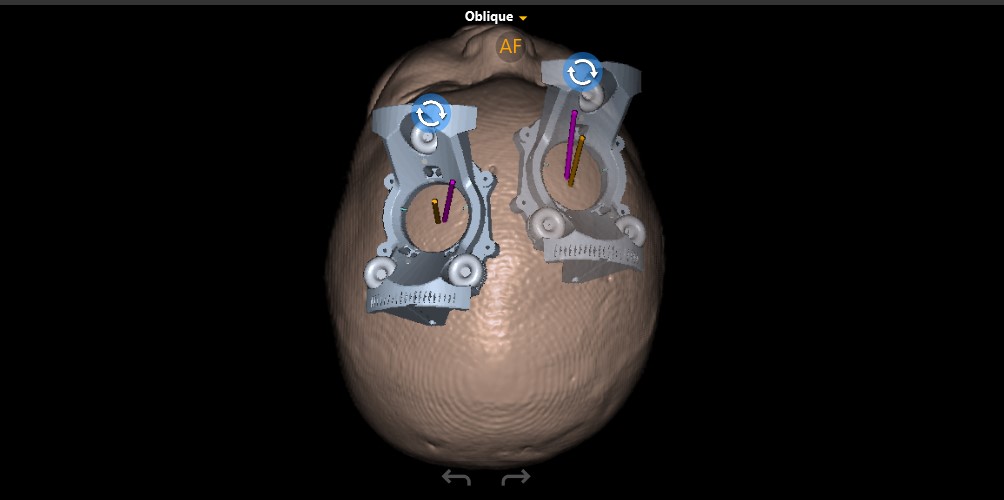

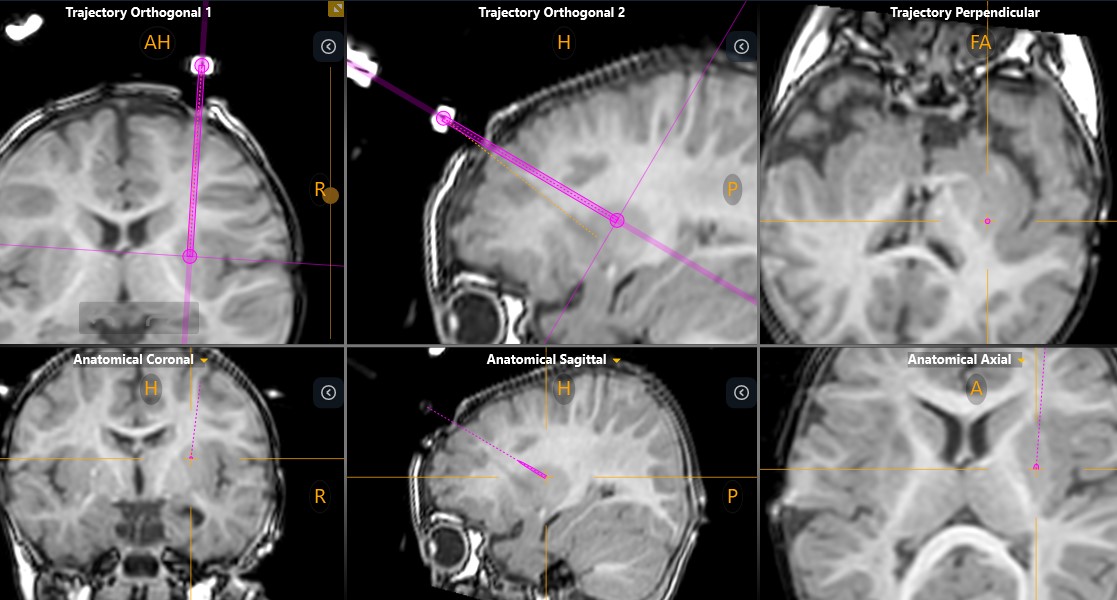

Doing this for a child as young and small as Sriansh required changing that procedure, a task that required the expertise of Sudhakar Vadivelu, DO, director of the Cerebrovascular Disease and Stroke Center at Cincinnati Children’s. Vadivelu and his team performed the advanced “stereotactic” brain surgery procedure using the ClearPointR Neuro Navigation System, which helped the surgeons guide probes to precise locations in Sriansh’s brain.

Prior to the procedure, the team performed multiple pre-surgical scans to map Sriansh’s brain. On the day of surgery, they attached several nickel-sized “fiducial” markers to Sriansh’s scalp to help position his head to line up with the digital map.

Using live MRI scanning to stay on-course, Vadivelu guided a minimally invasive catheter deep into Sriansh’s brain tissue to inject the engineered viruses into four tiny spots in the putamen. Precise delivery was crucial. Even a few millimeters off-target could make a significant difference in the outcome.

Modified procedure for the youngest patients

“People hear about gene therapy, but they don’t really understand how it’s delivered. In this case, we are talking about surgery on top of giving a gene therapy,” Vadivelu says. “Accessing that location of the brain required changes to their surgical protocol, which we developed here. That’s why we were able to treat the youngest patient.”

The modifications included changing the apparatus used during the procedure, moving the location and size of the burr hole used to expose the brain, and adjusting the anesthesia protocol. Vadivelu presented details about these modifications in November at a medical conference in Brazil.

“It’s one thing to say you have a 14-year-old or an 8-year-old. It’s another thing to say you have an 8-month-old or a 16-month-old,” Vadivelu says. “Adapting the procedure for the youngest children was important because the youngest patient has had one of the best outcomes. It’s a clear early difference right off the bat.”

For Sriansh, the procedure was a complete success.

After insertion, the engineered virus containing the missing DDC gene takes over. The virus invades targeted cells and sets up a tiny circular “factory” call an episome. This episome does not mingle with the brain cell’s DNA. But it produces the DDC protein endlessly so the pathway to make dopamine is restored.

Gilbert says being the youngest to receive the treatment helps explain why Sriansh has fared so well so far.

“When they were working out how to do it in Taiwan, how much virus to give, and so on, all the children were older. Sriansh got it around 16 months of age. There also has been a little girl in Boston who got the surgery at around 20 months. She’s also running around like he is,” Gilbert says.

For the Ojha family, being part of a clinical trial was intense, time-consuming and awe-inspiring all at the same time. So far, the outcome has been more than they dared to hope for Sriansh.

“I think it’s a miracle. It was a rough time, but it was worth it. I knew that no matter what I was going to try to save my child,” Bhawana says. “This sounds funny but deep down I knew my child would be OK.”

Next steps

Now that the therapy is approved, Gilbert says early diagnosis and early treatment will be crucial for maximizing treatment success for children with AADC deficiency. During initial clinical studies, several of the treated children were much older than Sriansh; some were nine years old and beyond. Not all of these children have regained their ability to walk, and some still show cognitive impairments, according to previously published data.

“However, it is now possible to diagnose this in a blood spot test, the same way we already diagnose PKU and other genetic conditions in a baby,” Gilbert says. “I don’t know whether the US or individual states will decide to include AADC testing in their newborn screens, but the reason they test for those things is that they are all things that you can treat early and help the child survive and have a better outcome. AADC is in the same group now.”

For other children with other genetic brain disorders, this success demonstrates that gene therapy might be possible for them as well someday. “This is the first time there has been a therapy where you put a missing gene directly into the brain,” Gilbert says.

Like the others receiving this new treatment, Sriansh will be followed for many years to track how he meets developmental milestones, both for motor and cognitive functions. In April, Sriansh had just completed another round of developmental exams.

“He did great. Oh my God, he was phenomenal,” a member of the therapy team told the family. “The physical therapist was especially impressed with all the new things he can do.”

At 32 months, Sriansh was performing tasks at about the level of an 18-to-24-month-old, which to Gilbert’s eyes meant that Sriansh had gained several months of progress in a matter of several weeks. How much further the progress will go, only time will tell.

Bhawana is focused on how Sriansh does with talking.

“He says Mama, Baba, Dada and he calls his sister DeeDee. But his words are not clear,” she says. “He also tries to copy words we say. I think that is very promising. At least he’s trying and that’s why I’m really happy.”