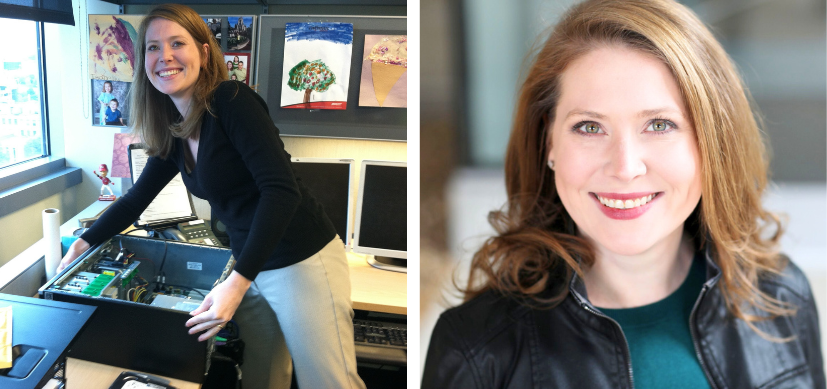

Road to Researcher: Leah Kottyan, PhD

Research By: Leah Kottyan, PhD

Post Date: August 28, 2025 | Publish Date:

What drives a scientist to unravel the mysteries of how our DNA influences disease? For Leah Kottyan, PhD—an immunologist, molecular biologist, leader and mentor at Cincinnati Children’s—it’s the thrill of transforming complex questions into life-changing insights.

Her research explores how subtle changes in our genome can shape our susceptibility to conditions like eosinophilic esophagitis, systemic lupus erythematosus, atopic dermatitis and multiple sclerosis—paving the way for new diagnostics, therapies, and hope for patients worldwide.

Today, as a professor in the Division of Allergy and Immunology, Kottyan leads innovative collaborations across the Center for Eosinophilic Disorders and the Center for Autoimmune Genomics and Etiology. With more than 140 publications, national recognition for her early-career research, and a deep commitment to mentoring the next generation of scientists, she exemplifies the spirit of curiosity and collaboration that drives discovery at Cincinnati Children’s.

Kottyan’s journey began here as a PhD student in 2005—and what started as a promising training opportunity evolved into a thriving career fueled by partnership, persistence and a passion for pushing the boundaries of science.

She recently shared more about her road-to-researcher journey.

What are some defining moments along your career path?

When I was a postdoc fellow, I realized someone in my division was doing research in a very different way and that if we worked together, we could achieve much more. I was doing genetic analysis in diseases of the immune system and Matthew Weirauch, PhD, a computational biologist, was studying DNA transcription factors and how they make certain processes happen. I remember wishing I could use all the computational approaches he used.

Together, we started studying how genetic variation changes disease risk and how transcription factors behave. This opened a huge area of research that was relatively uncharted at the time. (There are others working in the space now.) By hiring people together, writing grants and papers together, and bringing together multiple disciplines and ways of thinking, we have found that we can do things beyond what either of us could do individually.

We are very much partners. We bring people into our group with different expertise than us, such as physicists, developmental biologists, electrical engineers, immunologists, molecular biologists and chemists. When we come together to attack the same problem with different ways of thinking, we learn new things about life and discover new molecular mechanisms of disease and health.

Was there a mentor, project or experience early in your training that influenced your research direction or career decisions?

Marc Rothenberg, MD, PhD, was one of my PhD mentors. He discovered some of the early understandings about eosinophils, how they develop and what they do in disease. He was starting a medical service for children with these diseases. By the time I finished my PhD, gastroenterologists and allergists started appreciating that eosinophilic esophagitis was causing a lot of problems in children here and around the world.

I had the opportunity to collaborate with Marc to study the genetics of eosinophilic esophagitis. We published a paper in Nature Genetics, which became the platform from which I jumped into a faculty position and started my independent research.

It’s not typical to stay at the same place where you get your PhD. It’s important to get a lot of different perspectives on how to do research and how to ask different questions. But I had babies when I was a PhD student, and their dad had a job in Cincinnati.

I don’t do many things the way you’re supposed to. You’re “supposed” to show you are independent and not work with past mentors. My strategy is to do the best science I can, with the best scientists I can find, and if that happens to be with my mentors, okay.

Is there a particular project, collaboration or discovery at Cincinnati Children’s that you’re especially proud of?

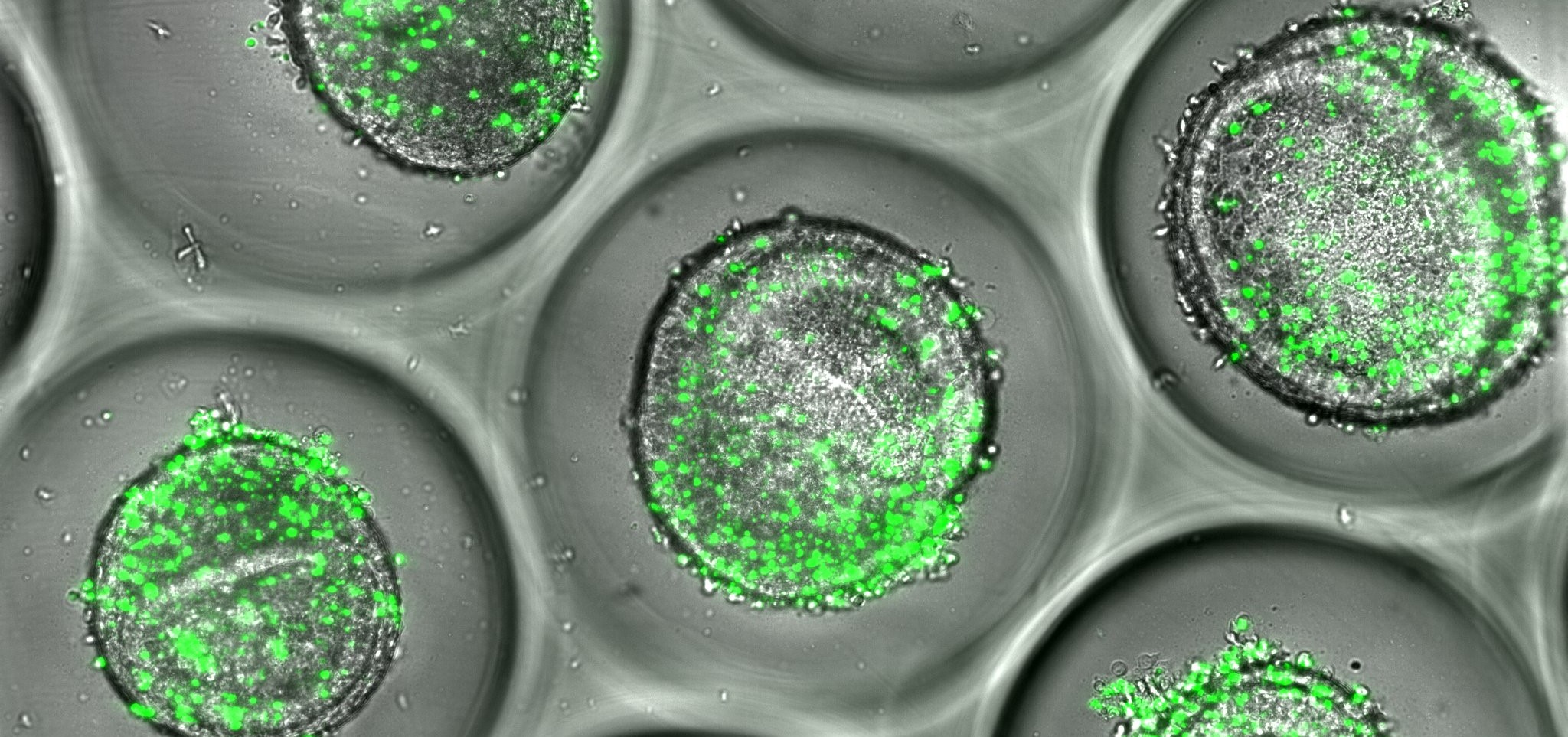

Matt [Weirauch] and I started exploring the genetics of autoimmune diseases. The DNA you’re born with can inform if you will get those diseases. But there’s also this huge environmental piece. There was increasing data about the role of viruses, and how early life viral exposures could influence what happens later in life. We were curious about how environmental and genetic pieces could come together. We started looking at the Epstein-Barr virus, which most people get. However, people with certain genetic variants unluckily develop chronic immune diseases after the initial infection.

We discovered that in this population, the Epstein-Barr virus enters a B cell and manipulates it. In some genetic contexts, the virus encodes proteins that rewires what the human genome is doing in a way that could lead to autoimmunity. The genetics are there. The environmental factors are there. And together they’re leading to this disease in a small number of people.

I like complicated systems and complex problems. Many people get the Epstein-Barr virus. Why do some of them go on to get lupus or multiple sclerosis? Figuring out what’s happening in that space is something that I think we have contributed to, and we’re going to keep studying. We’re looking at other viruses, too, because many physicians and researchers agree that some people get a virus and then later their health deteriorates in a chronic noninfectious way, but only after viral exposure. Trying to understand what’s happening is important.

What makes you stay? What keeps you motivated here?

The people I get to work with and who I have the privilege to train and learn from. It’s amazing how much you can learn from a learner. When somebody is in your group and they’re actively seeking information, oftentimes they’re asking questions in ways that you’ve never thought of, and you learn things by teaching them. Cincinnati Children’s is full of these cycles of academic generosity—where people are looking to support their colleagues, their trainees and all the groups around them.

I’ve stayed even when I had opportunities to leave because of the culture here. It’s an amazing place where we look out for each other and believe that when my neighbor scientist does well, we all do well.

If you could go back and tell your younger self one thing, what would it be?

It’s okay to break the rules in terms of what you’re supposed to do in your career. I had family members who told me PhD scientists didn’t make enough money to support their family. I’ve had colleagues say I would never get a faculty position if I stayed at the same institution for my postdoc as my PhD. I’ve had people tell me I would never get a grant if I continued to work with my old advisors. I’ve had people tell me that if I do too much institutional service, I’ll stop being able to publish and get grants. Every single one of those people was well-meaning, and they were wrong. It turns out that sticking to my core values and doing what I knew was right for me worked well. I doubted myself many times, but that is the advice I give others: Stick to your core values. There’s rarely one path to career success.

What’s something you have learned that has helped you navigate the challenges of a research career?

I took part in a year-long values-based leadership program through Cincinnati Children’s in 2015-2016. The goal of the program was to develop the core values important to you and learn to be a leader in the context of your values. When you make decisions for your career, as a leader or just in life, you don’t always have all the facts and can’t always make an analytical decision. You must go out on a limb and say, “I guess this is the right thing to do.” If you make decisions at these times by leaning on your values, you can be true to your most integral self and decide what’s right. Often, you can use those same values to determine what’s right for the institution and your group.

Now, as a leader, I’m able to share with my team what our group’s core values are. We can discuss those together. And we talk about how we make decisions when we don’t have all the information.

Outside of the lab, what helps you recharge?

My husband, four children, and Jack Russell Terriers are my joy. I also garden and write a gardening column for my neighborhood. I have a flower garden and a vegetable garden—I’m especially proud of my dahlias. I’m also the Lay Leader at my church. I enjoy giving back to the community.

Don’t Miss a Post:

- Subscribe to the Research Horizons Newsletter

- Follow Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation on Bluesky, X and LinkedIn

Research By

My laboratory studies the genetic etiology of diseases that have an immunological component.