Possible Treatment for Suppressed Immunity from Spine Injuries

Research By: Yutaka Yoshida, PhD,

Post Date: June 29, 2019 | Publish Date: April 18, 2016

Scientists report in Nature Neuroscience they have identified an underlying cause of dangerous immune suppression in people with high level spinal cord injuries and they propose a possible treatment.

In the journal’s April 18, 2016, online edition, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and Wexner Medical Center at The Ohio State University write that spinal cord injuries higher than thoracic level 5 (T5) cause autonomic nervous system circuitry to develop a highly adaptable state of plasticity. The autonomic nervous system controls bodily functions that are not consciously directed – like breathing, heartbeat, digestion and immune function.

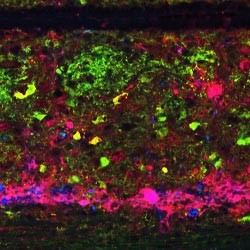

As the body rushes to react to spinal cord damage, new but abnormal nervous system circuitry starts to form, according to the authors. They show that in mouse models of spinal cord injury, this aberrant nervous system circuitry causes responses that extend beyond thoracic spinal segments, which in uninjured mice would normally feed nerves to secondary lymphoid tissues that help generate immune cells. Because of this, abnormal spinal interneurons are activated by the bladder and/or bowel. This results in formation of an exaggerated network of neural circuitry that activates an anti-inflammatory and immune suppressive reflex.

“Infection, a consequence of immune suppression, is the leading cause of death for people with spinal cord injuries,” said Yutaka Yoshida, PhD, co-lead author and a scientist in the Division of Developmental Biology at Cincinnati Children’s. “Patients and mouse models of spinal injury also are subject to autonomic dysreflexia, a potentially fatal clinical syndrome marked by episodes of high blood pressure.”

People with high-level spinal cord injury develop what is known as spinal cord injury-induced immune suppression syndrome (SCI-IDS). In the study, mouse models of high spinal cord injury have atrophied spleens (a secondary organ that produces white blood cells) and show signs of leukopenia (low white blood cell count).

Co-lead author Phillip Popovich, PhD, professor of Neuroscience and director of the Center for Brain and at Ohio State, said that “this abnormal spinal cord circuitry likely causes chronic immune suppression and increases the chance that people with spinal cord injuries will suffer from complications caused by common infections, such as pneumonia.”

In an effort to develop a possible treatment to stop immune suppression syndrome, the researchers tested chemogenetic agents in their laboratory mouse models. Chemogenetics involves manipulating receptors that are on the surface of cells and either activate or silence these cells. The use of chemogenetics creates the ability to exert very selective pharmacologic control over a variety of cell-signaling processes.

In the instance of mouse high spinal cord injury models, the researchers used chemogenetics to silence signaling transmissions from newly forming interneurons that trigger the immune suppression reflex. Because the newly forming nerves had specific genetic signatures, the scientists were able to control these neurons using a precisely targeted chemogenetic silencer (hM4Di-DREADD).

Chemogenetic silencing reversed the immune suppressive reflex in spinal injured mice. Atrophy in the animals’ spleens was reversed and white blood cell counts increased, the researchers report.

The researchers continue to test and refine the use of chemogenetic silencing to treat SCI-IDS. They caution that the experimental treatment method remains years away from testing in people with spinal cord injury.

Also collaborating on the study was first author Masaki Ueno, a member of Yoshida’s lab at Cincinnati Children’s and also the Japan Science and Technology Agency.

—By Nick Miller

Learn more about Developmental Biology research at Cincinnati Children’s

| Original title: | Silencing spinal interneurons inhibits immune suppressive autonomic reflexes caused by spinal cord injury |

| Published in: | Nature Neuroscience |

| Publish date: | April 18, 2016 |