Experimental Neck Collar Inspired by Woodpeckers and Bighorn Sheep Shows Promising Results

Research By: Greg Myer, PhD

Post Date: June 29, 2019 | Publish Date: July 2016

“The results of the studies demonstrate a potential approach to protecting the brain from changes sustained within a competitive football and hockey season, as evidenced by brain imaging.”

—Greg Myer, PhD

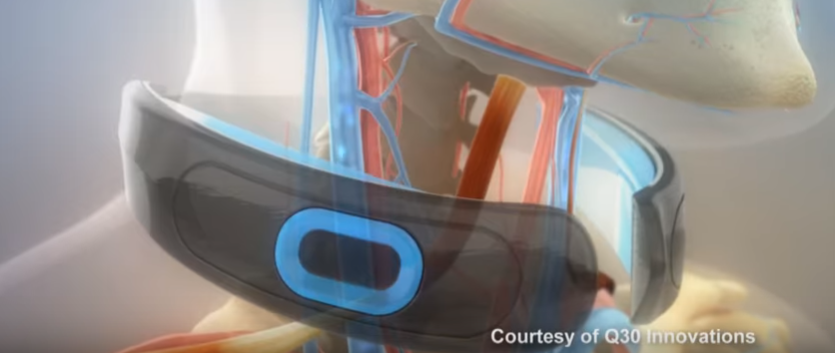

Two new studies involving high school football and hockey players indicate wearing a specifically designed compression collar may prevent or reduce the devastating effects of head collisions in sports. The neck device, called a Q-Collar, is designed to press gently on the jugular vein to slow blood outflow and increase the brain’s blood volume. The resulting effect helps the brain fit tighter within the skull cavity, reducing the energy absorbed by the brain during collisions.

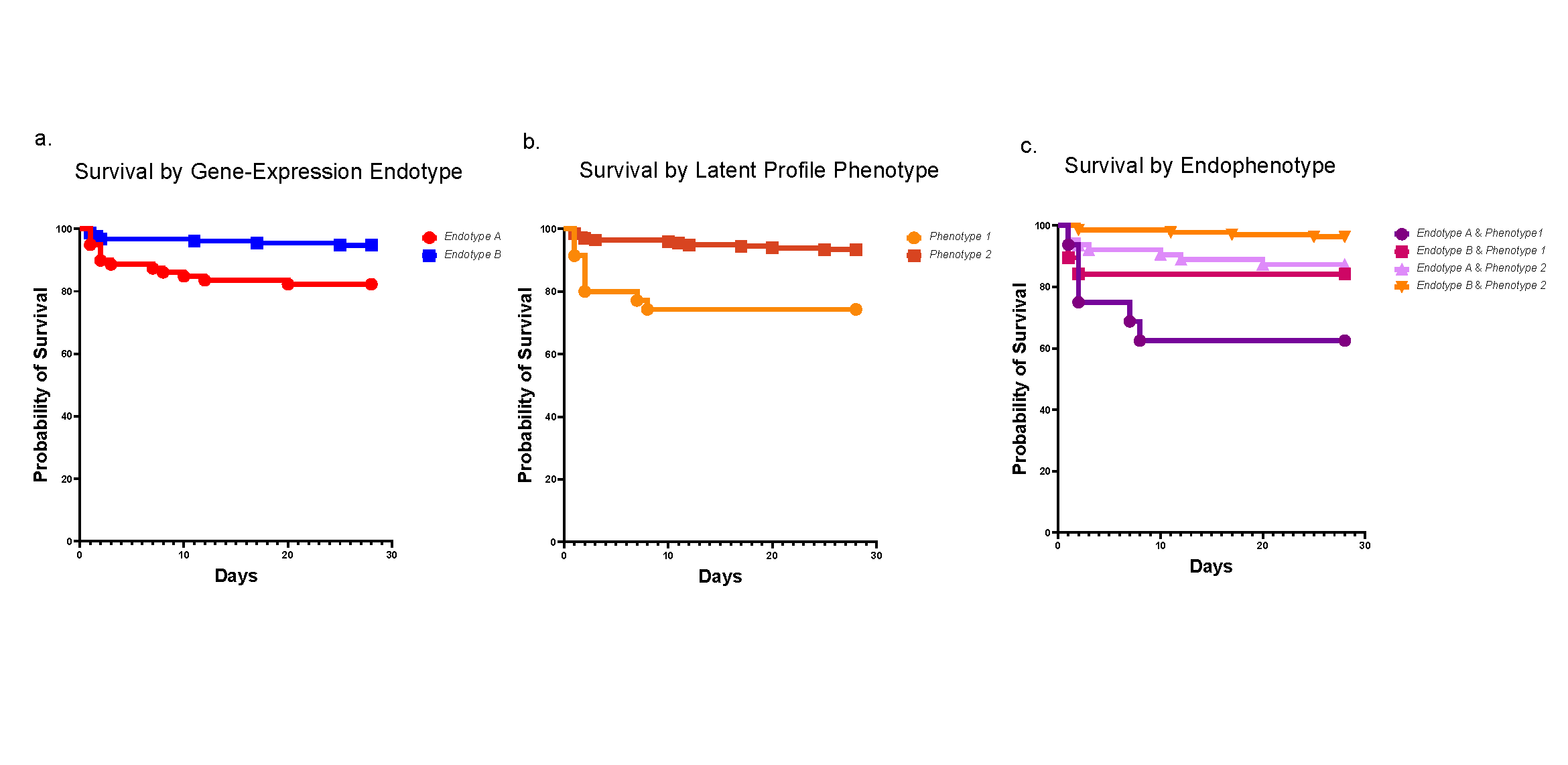

Analysis of neurophysiological and neuroanatomical data from the brain showed athletes in the non-collar wearing group had significant functional and structural changes to white matter regions of the brain but these changes were not evident in those who did wear the Q-Collar during play.

“White matter of the brain essentially connects all the pathways including structure and function. Neuro-radiologists at Cincinnati Children’s established a protocol for how the white matter in the brain is impacted after head collisions and what correlates to a brain injury,” said Greg Myer, PhD, director of sports medicine research at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center. Myer is the lead author of both studies.

In the preliminary study published in Frontiers in Neurology | Neurotrauma, 15 hockey players from St. Xavier High School took part. Half wore the collar for the hockey season and the other half did not. All helmets were outfitted with accelerometers to measure impacts. Results from the imaging and electrophysiological testing indicated that athletes in the non-collar wearing group experienced disruptions of brain microstructure and functional performance. Athletes wearing the collar did not show disruptions despite similar head impacts.

In a follow-up study published in the British Journal of Sports Medicine, 42 football players from two Greater Cincinnati high schools participated. Twenty-one athletes from St. Xavier High School wore the collar during a competitive season. They were tested before play to make sure the lightweight, c-shaped neck collar fit properly. The other half of athletes participating in the study were from Moeller High School. Those 21 players did not wear the collar.

All of the athletes’ helmets were outfitted with accelerometers to track hits sustained during the pre-and post-season. Researchers used advanced magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) techniques, including diffusion tensor imaging (DTI), to determine the efficacy of the collar to prevent structural changes to the brain. The results of this larger study showed similar protective effects.

“The results of the studies demonstrate a potential approach to protecting the brain from changes sustained within a competitive football and hockey season, as evidenced by brain imaging,” said Myer. “We still have more data analysis and investigation to do, but this device could be a real game-changer in helping athletes.”

This study follows previously published work by Myer regarding “brain slosh” and theories on how altitude influences concussions in football. Many football-related concussions are believed to occur because the brain doesn’t fit tightly in the skull. Cerebral blood flow rises at higher altitudes, causing the brain to fit tighter inside the skull, thus reducing the risk of a concussion. Historical approaches to protect the brain from outside the skull such as helmets have not been effective in reducing internal injury to the brain.

David Smith, PhD, co-author in the studies, researched bighorn (head-ramming) sheep and woodpeckers because both animals routinely tolerate high-speed cranium collisions with no adverse impact. A head-on collision between two rams can be 10 times greater than that of two football players; a woodpecker’s impact against a tree is 20 times greater.

The migration patterns of head-ramming sheep show they are hitting at high altitudes. With woodpeckers, they have a long tongue that wraps around the top of their head lassoing the jugular vein, which increases blood volume creating a natural bubble wrap to keep the brain from sloshing.

Q30 Innovations designed the neck collar and provided funding for the research. Performance Sports Group has licensed the technology from Q30 for use in sports worldwide and applied for FDA approval to market the device.

Smith has a financial interest in the results of the current research.

The study includes collaboration with the Pediatric Neuroimaging Research Consortium, and the Neurology Division, Radiology Division, and the Biostatistics and Epidemiology Department at Cincinnati Children’s.

—By Shannon Kettler

| Original title: | Analysis of head impact exposure and brain microstructure response in a season-long application of a jugular vein compression collar: a prospective, neuroimaging investigation in American football |

| Published in: | British Journal of Sports Medicine |

| Publish date: | July 2016 |

Research By