Mental Health Crisis is Real. So Are the Opportunities

Post Date: July 1, 2022 | Publish Date:

Former NIMH Director Sixth Prominent Speaker to Participate in Cincinnati Children’s ‘Envisioning’ Series

Tom lnsel, MD, says it’s time to change what we mean by mental health and behavioral health care.

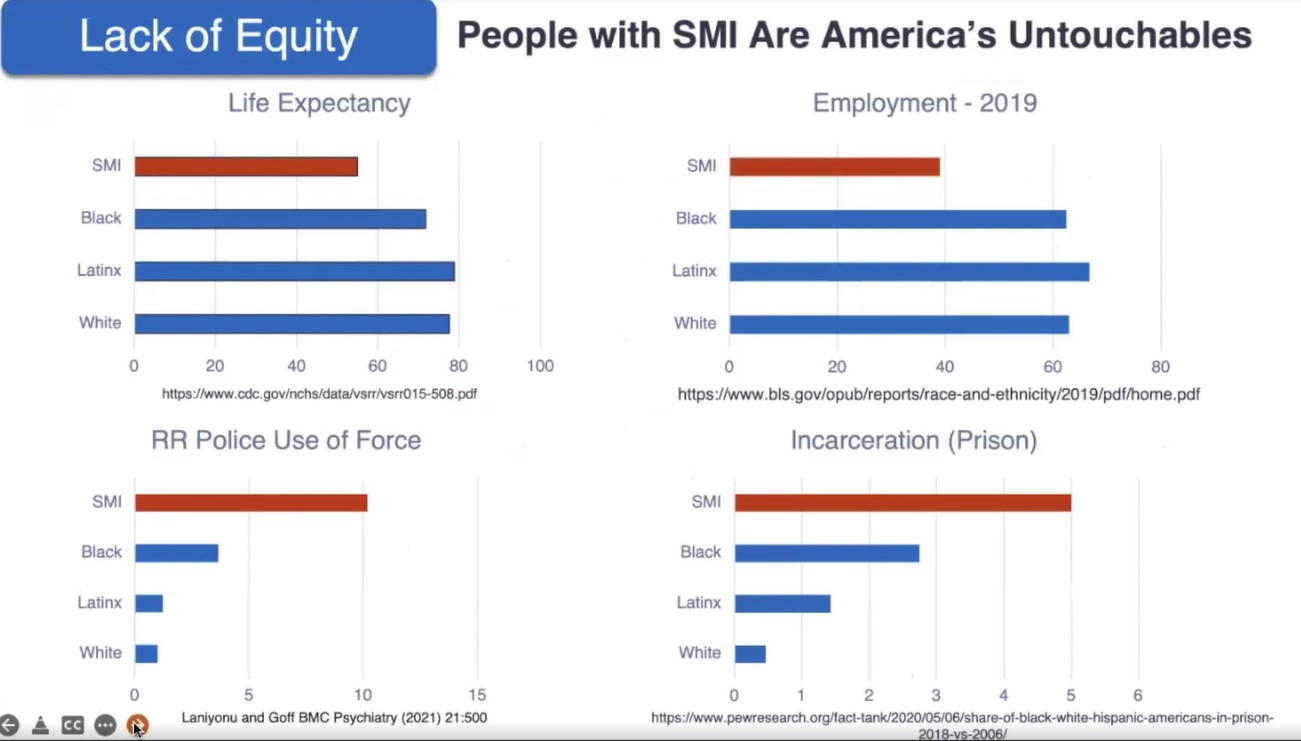

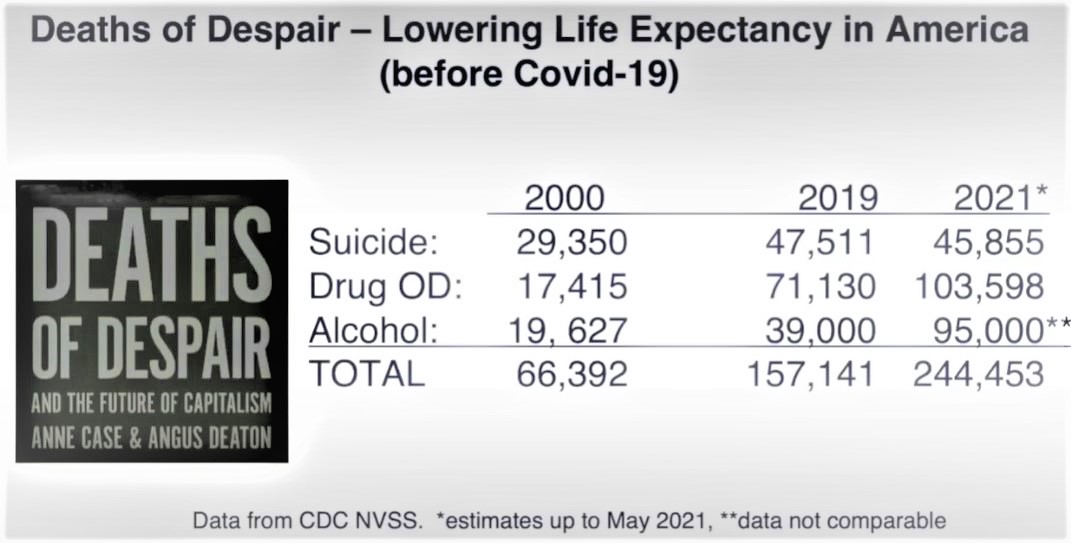

Despite significant advances in brain research and better-than-ever treatments reaching market, more people are dying from suicides and drug overdoses. And despite all efforts to reduce the stigma of mental illness, those suffering from schizophrenia, bipolar disorder and severe depression remain among America’s “untouchables.”

Be it incarceration, police use of force, employment opportunity, or limited life expectancy, people with serious mental health illnesses fare worse than virtually all other groups in key measures of health equity.

“You don’t have to be a person of color. Just having a serious mental illness puts you at higher risk of all these measures of inequity,” Insel says. “I think we have to begin to reckon that in our time, on our watch, the people with the most serious forms of mental illness have really been, in some ways, subject to the greatest injustices.”

Insel is a national leader in mental health research, policy, and technology who served as Director of the National Institute of Mental Health (NIMH) from 2002-2015.

With journalist co-founders, he also recently launched MindSite News, a non-profit digital publication focused on mental health issues. His latest book, Healing: Our Path from Mental Illness to Mental Health, was released earlier this year.

Insel spoke June 30, 2022, as part of the “Envisioning Our Future For Children” speaker series hosted by the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation.

For Young People, Deaths From Despair Outweigh Deaths From COVID-19

While COVID-19 has claimed more than 7,400 lives among those under age 30, deaths from despair have resulted in more than 90,000 deaths among those under 34 during the pandemic years, Insel says.

“I think we are not coming to terms with this as a public health problem in the way that we need to. Part of why I wrote the book was to call these numbers out,” Insel says.

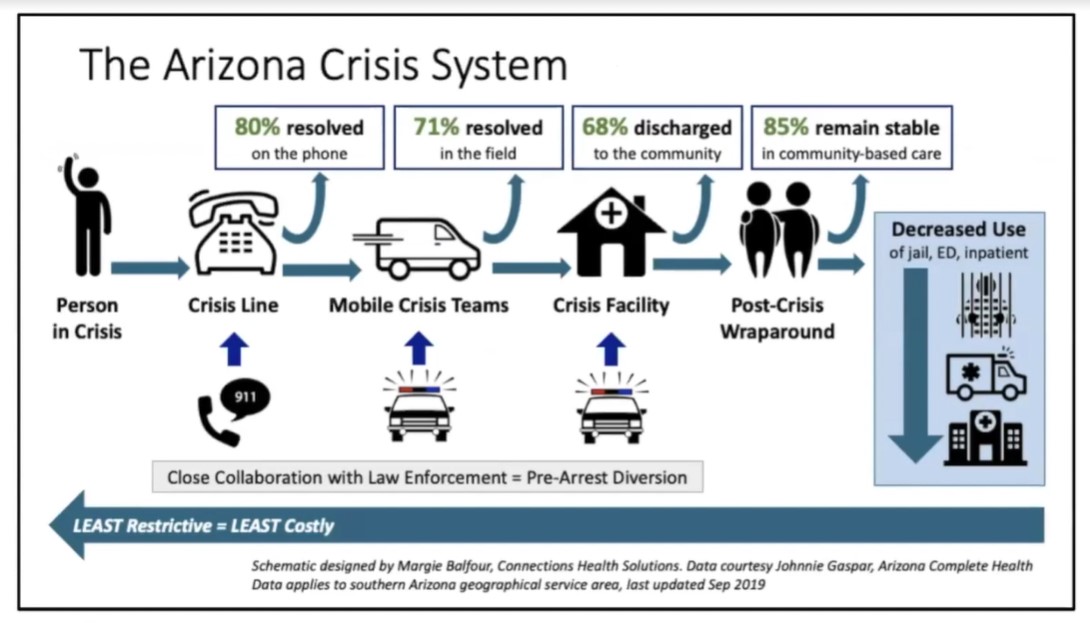

One of the first steps toward reducing the deep injustices in the mental health system is to begin reforming the nation’s crisis response approach. While statistics show that police-driven response to mental health situations often leads to tragedy, some places have shown success at not using police.

In Tucson, AZ, Insel says a crisis response team approach has made improvements by having phones answered by telehealth providers versus police dispatchers, by sending care professionals out as responders, and when needed, taking people to mental health facilities rather than jails.

More cities and other states are beginning to explore similar types of crisis response programs. Insel says these responses will require much work to ramp up across the country starting July 16. That’s when the new 988 emergency number for mental health calls takes effect nationwide.

Learn More About the New 988 Number

Unfortunately, even though the phone numbers might go live, many places across the country are not yet staffed and prepared to respond to calls like Tucson does, Insel says.

Time to Shift the Model

Insel says the medical treatments for mental illness are vastly improved compared to decades ago. But the crisis in mental health is less about good medicines and far more about failing to reach the people in need–and worse–failing to stick with them.

“We have unprecedented progress in neuroscience, behavioral science and technology. We have effective interventions for virtually every mental illness. We can honestly say we have good stuff to offer. They’re not perfect but they are pretty effective,” Insel says.

“We are seeing more patients than ever, and we are doing better with those patients than ever before. At the individual level, the story is very positive. People are getting better. Yet at a population level, the outcomes are worse.”

The oft-shared statistic that 60 percent of those who need mental health treatment do not receive it does not paint the full picture, Insel says. He uses a “40-40-33 rule” instead. Of the 40% receiving care, only 40% of those people are receiving evidence-based minimum standard care. And of those, only about one-third actually become well.

That means slightly more than 5% of those treated have experienced fully successful outcomes in our current system, Insel says.

Now, Insel supports pushing the system toward a longer-term recovery model.

“The problem is medical but solutions are much broader,” Insel says. “They are social, environmental, and even political.”

A recovery model goes beyond acute care to focus on people, making sure they have a place to turn and helping them find the purpose they need not just to be treated, but to thrive, Insel says.

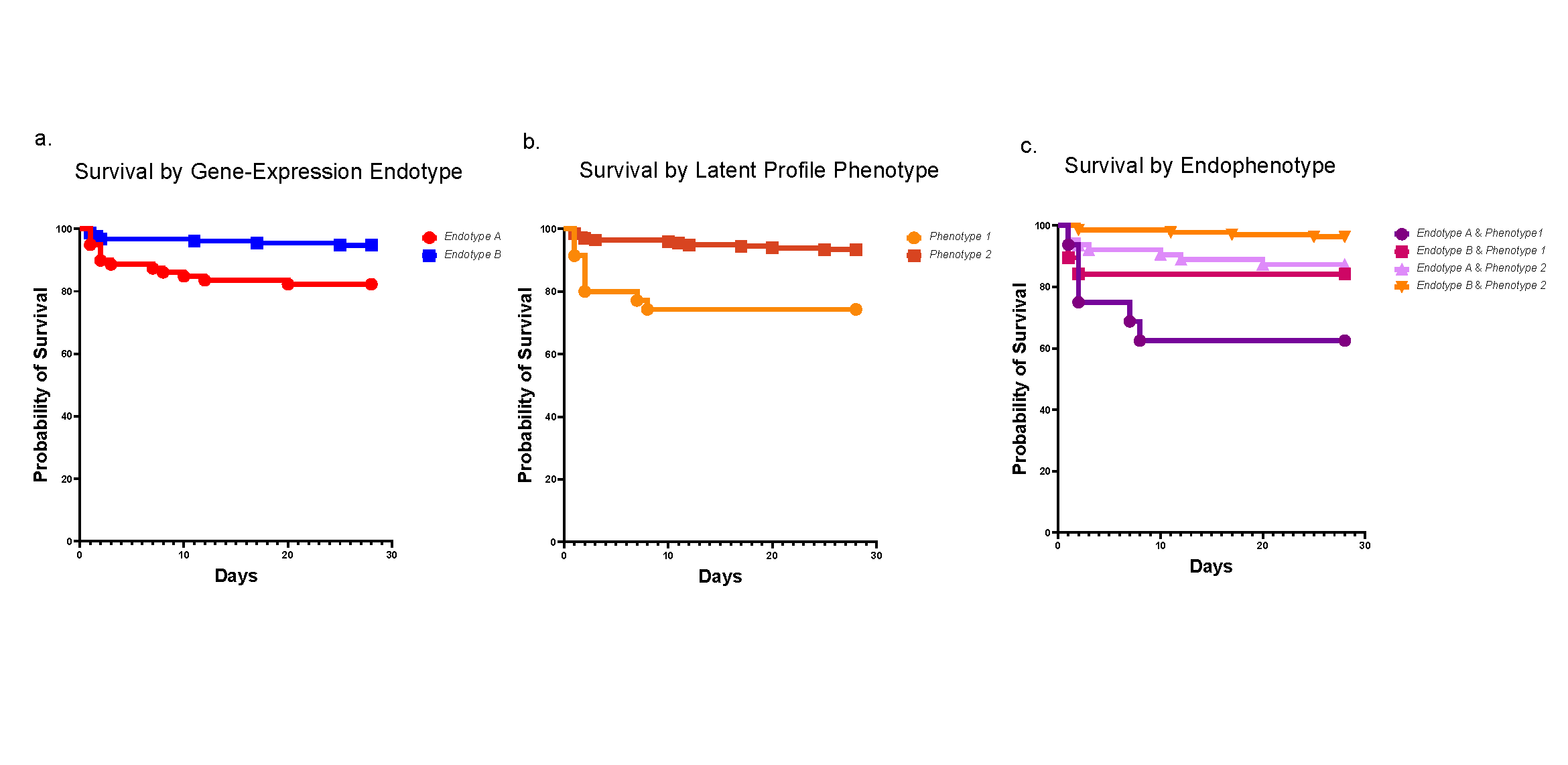

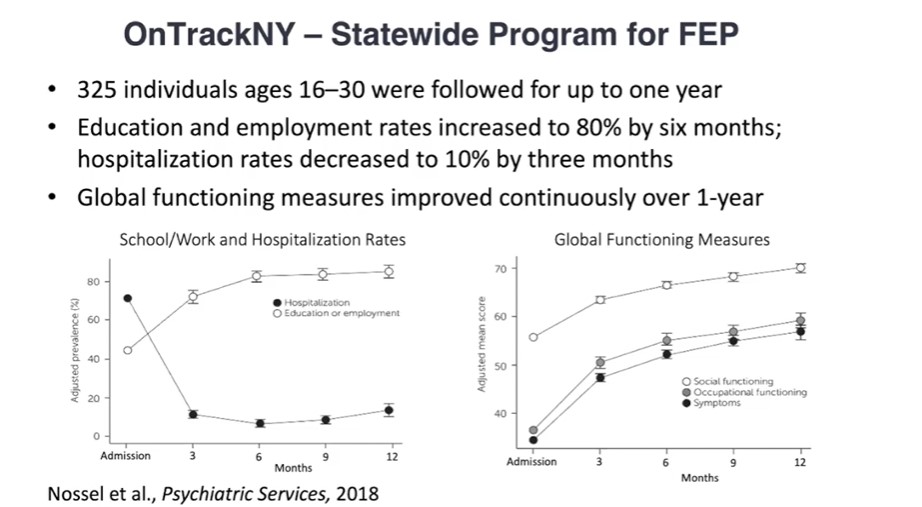

He points to “coordinated specialty care” programs in New York that are finding success at preventing second episodes of psychosis with a suite of follow-up services and support programs that help with employment and education in addition to medications and counseling.

Opportunities ahead

Insel says real money is starting to flow into improving mental health care, from billions being invested by venture capitalists in telehealth and related digital health technologies, to more than $9 billion in federal funds heading toward Certified Community Behavioral Health Centers in the wake of the mass shooting in Uvalde, TX.

He notes that California has committed $4.4 billion over five years to build its Child and Youth Behavioral Health Initiative. In addition to expanding increasingly popular telehealth services, this effort also focuses on child-parent dyads–a vital way to reduce adverse childhood events (ACEs) that can have life-long health impacts, Insel says.

“These are enormously exciting developments,” Insel says. “There are more changes and opportunities happening in the mental health space than I’ve seen at any time in my nearly 50 year career.”

Much work ahead

Tina Cheng, MD, MPH, Director of the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation, Chair of Pediatrics at the University of Cincinnati and Chief Medical Officer at Cincinnati Children’s, thanked Insel for his comments. She notes that most mental health conditions begin early in the life course, which means pediatric medical centers play a crucial role in addressing the entire mental health crisis in America.

“We are committed to addressing the mental health crisis we are seeing. We are the children’s hospital with the largest number of psychiatric beds. (100 acute care and 30 longer-term residential) We also have the largest psychology department working on prevention,” Cheng says. “But despite all that, our house is still on fire. The demand is huge.”

Get information about upcoming speakers Diana Bianchi, MD, and Robert Langer, ScD.

Learn More

Find the book: Healing: Our Path From Mental Illness to Mental Health

Follow Insel on Twitter: @thomasinselmd