Family-Led Fundraising Drives Discovery in Rare Mitochondrial Disease Research

Research By: Taosheng Huang, MD, PhD

Post Date: January 31, 2020 | Publish Date: Jan. 16, 2020

Five-year-old Hadley Jo Brindley has an extremely rare disease and an extremely determined set of parents and hometown supporters in Bowling Green, KY. And thanks to the funds they have raised, a scientist at Cincinnati Children’s is making significant progress in his quest for a cure.

In the span of just five years, a mitochondrial disorder known to affect only a few dozen people in the world has moved from discovery to early signs of success for a potential gene therapy. Details of the work, led by Taosheng Huang, MD, PhD, and colleagues were published Jan. 16, 2020, in the journal Human Molecular Genetics.

“We know it’s still too early to know if all of this will help Hadley, but I do believe God put us with Dr. Huang,” says Ashley Brindley, Hadley Jo’s mother. “We’re not only helping Hadley but other children and adults too that are suffering with this.”

“This” is a condition so uncommon it has more of a label than a name: hereditary motor and sensory neuropathy, type VIB—also called HMSN6B for short. In essence, a malfunction in Hadley’s mitochondria—the energy-processing component of all our cells—is gradually affecting her eyesight, limiting her ability to walk, and interfering with her brain development.

Just having the condition diagnosed was an enormous challenge for the family.

Twisting Road Leads to Cincinnati Children’s

Hadley Jo seemed healthy when she was born in May 2014. But during her first year, she started missing milestones. Her parents Ashley and Casey began to notice that she was having difficulties learning to walk and abnormalities in her eye movement.

When they brought Hadley in for an 18-month check-up, their pediatrician referred the family to an optometrist. Upon seeing Hadley Jo’s delayed motor skills, the optometrist referred the family to a pediatric ophthalmologist at Vanderbilt Children’s Hospital, about 70 miles south in Nashville, TN.

There, an MRI scan quickly detected abnormalities in Hadley Jo’s cerebellum—the “little brain” near the brain stem that controls most motor skills. This explained why she was having difficulty walking, but it took another year of testing to determine that Hadley Jo had a gene “error” that none of the experts at Vanderbilt had seen before, her mother Ashley says.

This was an alarming situation because Vanderbilt is nationally known as a high-quality medical center. Ashley was unsure what further steps could be taken, but she had no plans to stop taking steps.

“Me being the type of person that I am, I decided to see what I could find on the internet,” Ashley said.

The hunt required wading through dense scientific references like the information posted by the “Online Mendelian Inheritance in Man,” a genetics library created by Johns Hopkins University as a tool for genetic researchers and advanced medical students. But the work paid off.

“I saw that Dr. Huang was doing research on this. So, I reached out to their team, told them our story and asked if they’d be willing to meet with us. They said ‘yes’ pretty much immediately,” Ashley says.

After talking in December 2016, the family drove about 225 miles north to Cincinnati in February 2017 for Hadley’s first visit with Huang and his team.

Even Without a Cure, an Answer and a Call

Ashley had learned on her own that Huang was a noted authority on mitochondrial disorders. In fact, he was the co-corresponding author of a 2015 research paper that reported discovering a gene mutation that produced symptoms closely matching Hadley Jo’s experience. The other co-corresponding author was Stephan Zuchner, MD, PhD, at the University of Miami in Florida.

They described HMSN6B is as a progressive neurologic disorder that appears at first with symptoms of early-onset optic atrophy resulting in progressive visual loss. Those affected also experience a range of peripheral nerve malfunctions as well as cerebellar atrophy that can lead to various abnormal types of movement.

In one sense, Hadley Jo reaching age 5 means she’s among the more-fortunate cases. Experts say the most severely affected patients die in early infancy.

When the 2015 paper was published, the team had found only four families, including one in the United States, one in the United Kingdom, one in Italy, and one in the United State with Palestine origin. By the time Huang confirmed that Hadley Jo also had the condition, the known number of cases had grown to about 20.

The exact number of people with this gene abnormality remains unknown but is likely to grow as more children get tested, Huang says. That’s because some children living with the condition may have been diagnosed with other disorders. It also is very likely that some children with disease-causing mutations in the SLC25A46 gene have died without being tested and diagnosed.

Yet after enduring more than three years of not knowing Hadley’s condition, having a diagnosis was a relief.

“Just that alone was amazing,” Ashley says. “We wished she had something different, something easy to fix, but at least now we know what we’re up against.”

A New Battle Begins

It did not take long for the Brindley family to encounter a challenge well-known to many families of children coping with rare diseases—the scarcity of funding for research.

“I think it was back in January or February of 2019 when Dr. Huang and I were talking,” Ashley says. “We know that within research centers the money gets divvyed up to lots of different places, and if it’s a less well-known thing, the money gets smaller and smaller. But Dr. Huang told us about a family in California. Their child had a different disorder, but they launched a foundation several years ago that made a big difference.”

Could the Brindleys do something similar?

“Casey and I, we thought about it, prayed about it, and decided that’s what we wanted to do,” Ashley says. “So, we set it up and we got it approved by the state of Kentucky on March 22 as a non-profit so we could start raising funds.”

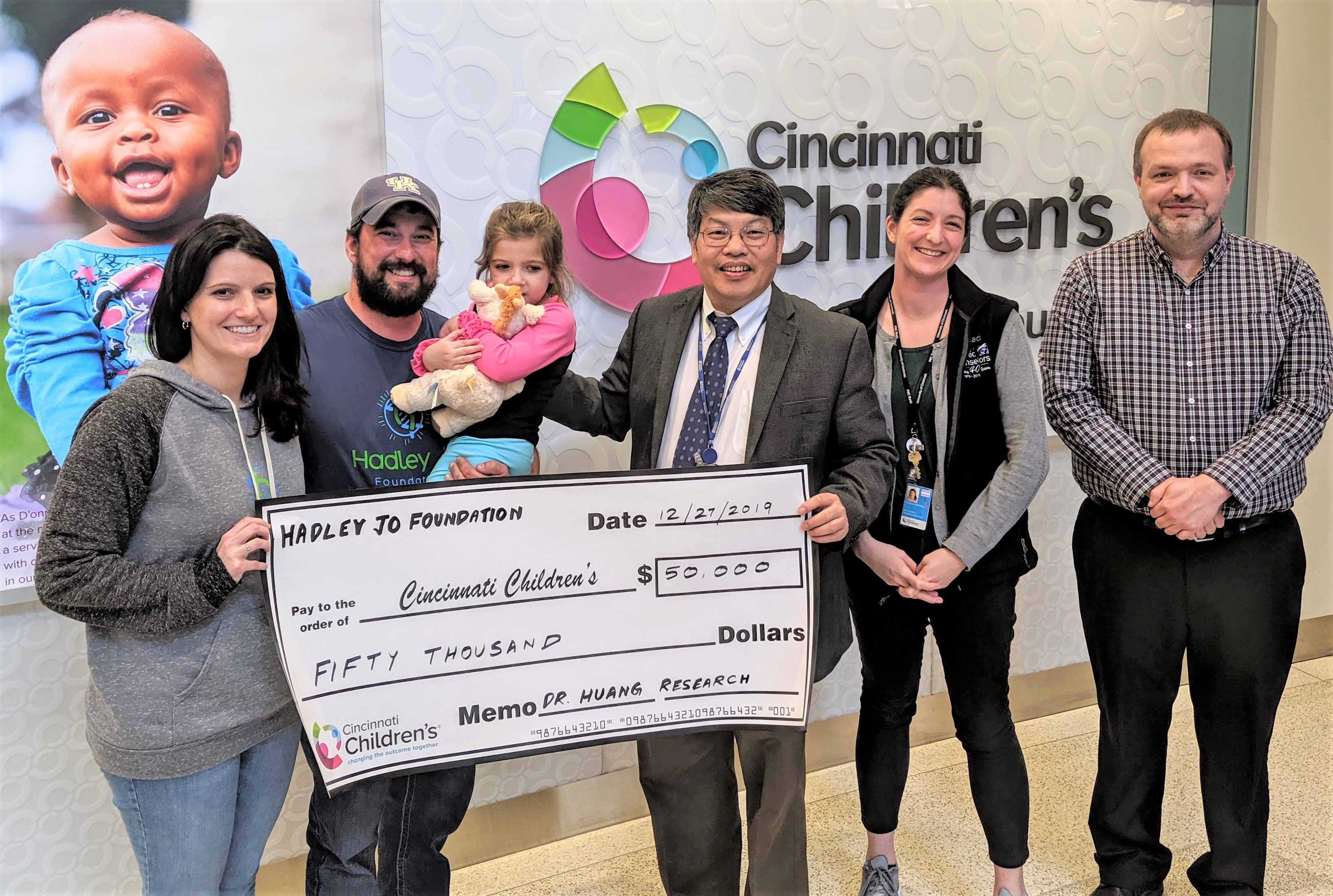

The new Hadley Jo Foundation got to work, raising funds in various ways including a summer barbecue and a November dinner. In July, the family returned to Cincinnati Children’s to present a $30,000 donation, then another $50,000 in late December—fuel for more research.

“It was great to have Dr. Huang and his team come down to Bowling Green. They did a presentation to explain the condition and the research they had done so far,” Ashley says. “Hadley’s condition is so rare, just getting people to understand what it is was so helpful.”

A Long Road Ahead

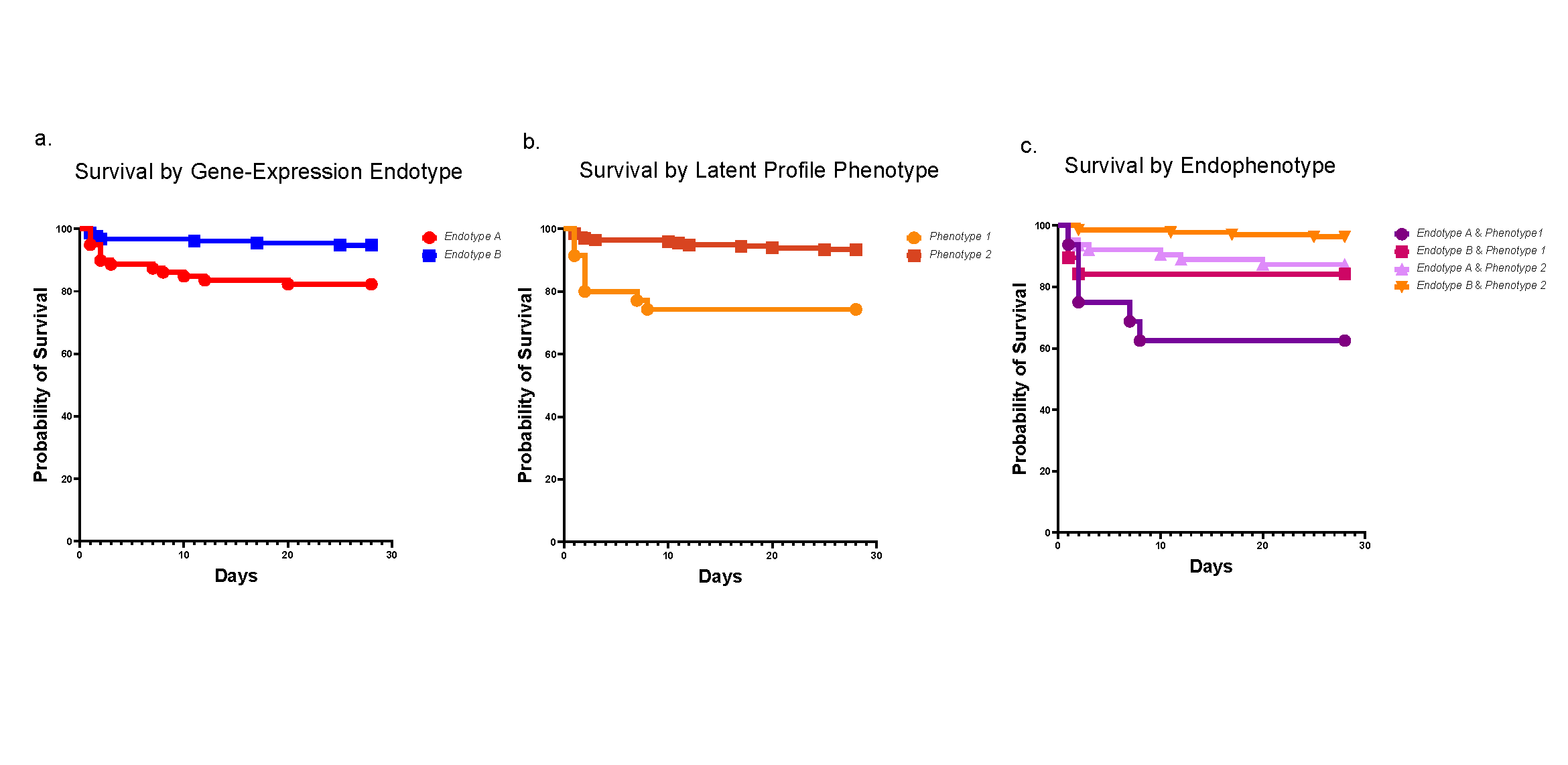

Huang and the Brindleys are excited about the new findings published in Human Molecular Genetics. The scientists report that gene therapy—using a modified virus to deliver a healthy version of the defective gene SLC25A46a–appeared to be effective at treating the disorder. The treatment prevented premature death, improved nerve function and mobility, and restored mitochondrial activity in many cells.

But for now, these successes are limited to mice. Much more work must be completed before attempting the treatment in humans. The next steps, Huang says, include building a registry of other people with this condition. The more people the team can find, the quicker the work will go to begin a clinical trial.

In the meantime, Huang and other doctors and therapists at Cincinnati Children’s and in Bowling Green, are working to manage Hadley Jo’s symptoms. Some medications already exist to support mitochondrial function, Huang says. Physical therapy and other support services also help.

As Ashley writes on the foundation website, the work continues.

“Our journey has been a long and bumpy one, but the good that we’ve seen come from this in our communities is astonishing,” she writes. “The love and support we have received for this foundation has been nothing short of incredible. On behalf of the entire Brindley family, we are beyond grateful for the contributions and sacrifices we’ve seen so many people make for our daughter.”

| Original title: | Systemic administration of AAV-Slc25a46 mitigates mitochondrial neuropathy in Slc25a46−/− mice |

| Published in: | Human Molecular Genetics |

| Publish date: | Jan. 16, 2020 |

Research By