Deeper Microchimerism Study Sheds New Light on a Mother’s Cellular Gift

Research By: Yanyan Peng, PhD | Sing Sing Way, MD, PhD

Post Date: September 30, 2025 | Publish Date: Sept. 9, 2025

Offspring carry maternal cells in many tissues, but only some have cross-generational influence upon the immune system. Others play still-unexplained roles

A series of studies in recent years reveals that mothers contribute even more than inherited DNA to their children—they also pass along fully formed cells that continue functioning for years within their offsprings’ bodies. It’s a phenomenon scientists call microchimerism.

Fetal microchimeric cells can be found in virtually all maternal tissues including the liver, blood, bone marrow, heart, lungs, and other tissue types after pregnancy. Previous research led by experts at Cincinnati Children’s has shown that these persistent cells are not accidental souvenirs of pregnancy, but play a surprising role in helping mothers “remember” previous pregnancies so that their immune systems better tolerate a fetus that expresses foreign traits derived from the father.

These findings are changing our understanding of how a mother’s immune system changes after pregnancy, which could lead to improved ways to protect against pregnancy complications such as prematurity, preeclampsia and stillbirth associated with premature fetal rejection.

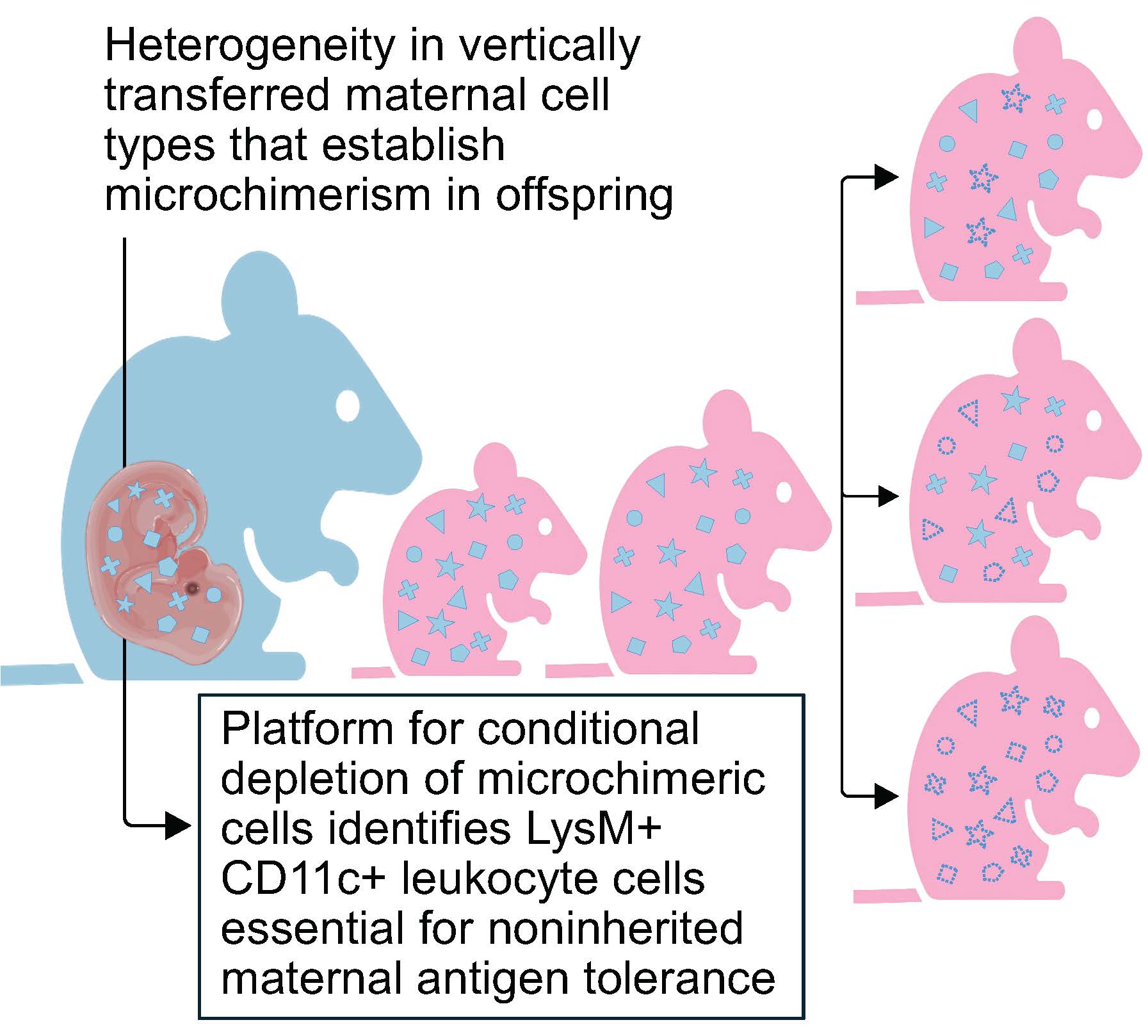

Meanwhile, scientists also have been finding that children are equally receptive to retained mothers cells, with approximately one in every million cells in our bodies being of maternal origin. Considering we are composed of nearly 30 trillion cells, this means we all contain millions of our mother cells. The heterogeneity of these exceptionally rare cells have made scientists struggle to identify what these do and how they work. Now, a new study led by Sing Sing Way, MD, PhD, and eight colleagues at the Center for Inflammation and Tolerance at Cincinnati Children’s reports two major findings:

- Only a specific very small proportion of maternal microchimeric cells — marked by the proteins LysM and CD11c — are involved in influencing how children immunologically tolerate their mothers or non-inherited maternal antigens. These cells and the proteins they produce are important for preventing pregnancy complications in the next generation.

- The team made these observations after developing new tools for experimentally manipulating only defined types of MMc in offspring.

Details were published Sept. 9 in the journal Immunity.

“This study highlights several exciting facets regarding maternal microchimeric cells” Way says. “While they can promote immune tolerance and replace missing proteins in the case of autosomal recessive disorders, eliminating only the cells that promote tolerance still does not eliminate the majority of these cells. The new tools we developed to study these cells will help scientists pinpoint exactly what these cells do and how they work in a variety of contexts including autoimmune disease, cancer and neurological disorders.”

At a nearly metaphysical level, the unexpectedly wide range of microchimeric cells passed between mothers and their children reveals that cells in our body not only express our own DNA, but also DNA exclusive to our mothers, or for mothers, DNA exclusive to their children. Understanding how these cells escape rejection and selectively tone down the immune system can pave the way to new therapies to protect against pregnancy complications, treat autoimmune diseases, and help people better tolerate organ transplants.

“Microchimerism is increasingly linked with so many health disorders. This study provides an adaptable platform for scientists to investigate whether these rare cells are the cause of disease, or alternatively, found in diseased tissue at increased levels as part of the natural healing process,” Way says.

Next steps

Discovering that non-inherited maternal antigen tolerance depends specifically on a very small proportion of maternal microchimeric cells that co-express LysM and CD11c lets us focus in on these specific rare among super rare cells to better understand how they promote classical immune tolerance.

Meanwhile, confirming that most maternal microchimeric cells can persist despite “erased” tolerance raises new questions about why these cells are not rejected, and the existence of alternative pathways allowing foreign cells to persistent indefinitely in individuals.

“Our approach allows us to deplete microchimerism across any cell type, which had not been possible previously,” Way says. “This will allow us and others to zero in on specific cell types that promote protective or detrimental phenotypes.”

About the study

Cincinnati Children’s researchers involved in this study included first author Yanyan Peng, PhD, Giang Pham, PhD, Jiahui Sun, PhD, Ujjwal Adhikari, MS, Sudeep Kumar, PhD, Tzu-Yu Shao, PhD, (now with Amgen), Jeremy Kinder, PhD, (now with Sound Biologics) and Lucien Turner, PhD.

Experiments conducted for this study included support from the NIH Tetramer Core Facility and the Cincinnati Children’s Research Flow Cytometry Facility and the divisions of Veterinary Services and Rheumatology.

Funding sources included grants from the NIAID (DP1AI131080, R01AI175431, R01AI184537, and T32AI165396); the HHMI Faculty Scholars Program, the Burroughs Wellcome Fund, and the March of Dimes Ohio Prematurity Research Collaborative.

Don’t Miss a Post:

- Subscribe to the Research Horizons Newsletter

- Follow Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation on Bluesky, X and LinkedIn

| Original title: | Tolerance to non-inherited maternal antigen is sustained by LysM+ CD11c+ maternal microchimeric cells |

| Published in: | Immunity |

| Publish date: | Sept. 9, 2025 |

Research By

My research interests include infectious diseases, reproductive biology, developmental biology and immunology.