COVID-19 Vaccines Revisited: Uptake Status and Remaining Questions

Post Date: June 14, 2021 | Publish Date:

On June 9, 2021, Paul Spearman, MD, Director of the Cincinnati Children’s Division of Infectious Diseases, and Robert W. Frenck Jr., MD, Director of the Cincinnati Children’s Vaccine Research Center, wrapped up a seven-part Current Topics in COVID-19 Research Seminar Series and co-presented on some of the latest updates surrounding COVID-19 vaccines (click here to watch the recording).

During their presentation, Spearman discussed the rise of the new SARS-CoV-2 variants, domestic and global vaccine strategies, and second-generation vaccines being developed. Frenck provided an update on COVID-19 vaccine clinical trials currently underway, including moving vaccines into pediatric age groups.

WHY HAS THERE BEEN SO MUCH VARIATION FOR THE COVID-19 VIRUS?

Spearman first reviewed the basics of coronavirus variation.

Coronaviruses have an RNA-dependent RNA polymerase, which is the replication machinery for all RNA viruses. It sometimes makes errors, which contributes to variants arising, but coronaviruses also have an unusual proofreading enzyme that other RNA viruses don’t have.

So why has there been so much variation for the COVID-19 virus? Spearman described a couple of reasons.

“First of all, it’s not perfect,” he responded. “So even with the proofreading, there’s still some low rate of mutagenesis or substitutions that occur.”

Other potential sources of variation include the global scale of the COVID-19 pandemic, immunocompromised individuals who have prolonged infection where the virus can replicate, and extensive viral recombination.

WHAT ARE THE COVID-19 VARIANTS OF CONCERN?

Spearman defined the term variants of concern, which are variants that show evidence of increased transmissibility, more severe disease, significant reduction in neutralization by antibodies generated during previous infection or vaccination, reduced effectiveness of treatments or vaccines, or diagnostic detection failures.

He discussed each of the four SARS-CoV-2 variants, why they’re concerning, and identified which ones may escape vaccine-induced neutralization.

The U.K. variant (B.1.1.7) is the most common variant in the U.S. and is approximately 50% more transmissible than the Wuhan strain. Evidence suggests it is not associated with higher disease severity and has no effect on the efficacy of monoclonal antibodies.

“There’s a slight reduction of neutralization by convalescent sera from those who have had the infection, but the vaccines remain completely active against the U.K. variant,” Spearman said.

The South African variant (B.1.351) is a dangerous variant and has a particular mutation that is linked to immune escape.

“The evidence is pretty clear that it doesn’t really cause more severe disease, but it is harder to neutralize,” he said. “If you take vaccine sera from those who have gotten the current vaccines, they neutralize the virus, but much less well.”

The Brazil variant (P.1) has the same two mutations as the U.K. and South African variants, appears to be more transmissible, and has the characteristic of not being neutralized as well by vaccines.

“The Indian variant (B.1.617) doesn’t look quite so frightening, but everyone’s keeping an eye on it because it is more transmissible,” Spearman said.

It has a slight reduction in neutralization titers, but preliminary evidence demonstrates that the COVID-19 vaccines still provide very effective protection.

“Continued surveillance is going to be important,” he said. “Variants are going to continue to arise as long as we have a global pandemic and as long as there are pockets of people who are not immunized.”

Spearman reassured viewers that COVID-19 vaccines will still work against these variants and protect against severe disease.

“Major variants in the U.S. are still sensitive to all of our authorized vaccines,” he said. “There’s no reason to panic about any of this.”

HOW DO WE DEAL WITH THE COVID-19 VARIANTS?

Spearman offered some potential ways to deal with the COVID-19 variants from a vaccine standpoint and discussed second-generation vaccination strategies, including approaches under investigation.

“Booster vaccines are likely to be needed,” he noted. “How long will that durability of protection be? It will depend on the vaccine.”

Next-generation vaccines include new routes of delivery (e.g. intranasal, replicating vaccines), broadened immunity versions designed to stimulate cellular immunity, and pan-coronavirus vaccines that can protect broadly against pathogenic coronaviruses.

WHY DO WE NEED COVID-19 VACCINES IN CHILDREN?

Frenck’s presentation focused on pediatric COVID-19 vaccine trials and related updates.

He first reviewed the COVID-19 vaccine trials at Cincinnati Children’s for Pfizer, AstraZeneca, and Moderna, as well as future studies involving pregnant women, immunocompromised individuals, stability, and second-generation vaccines.

“To date, we’ve enrolled over 1,500 people in the combined studies,” he said. “One of the questions I ask get asked a lot is ‘why do we need COVID vaccines in children.”

First, there are direct effects upon children.

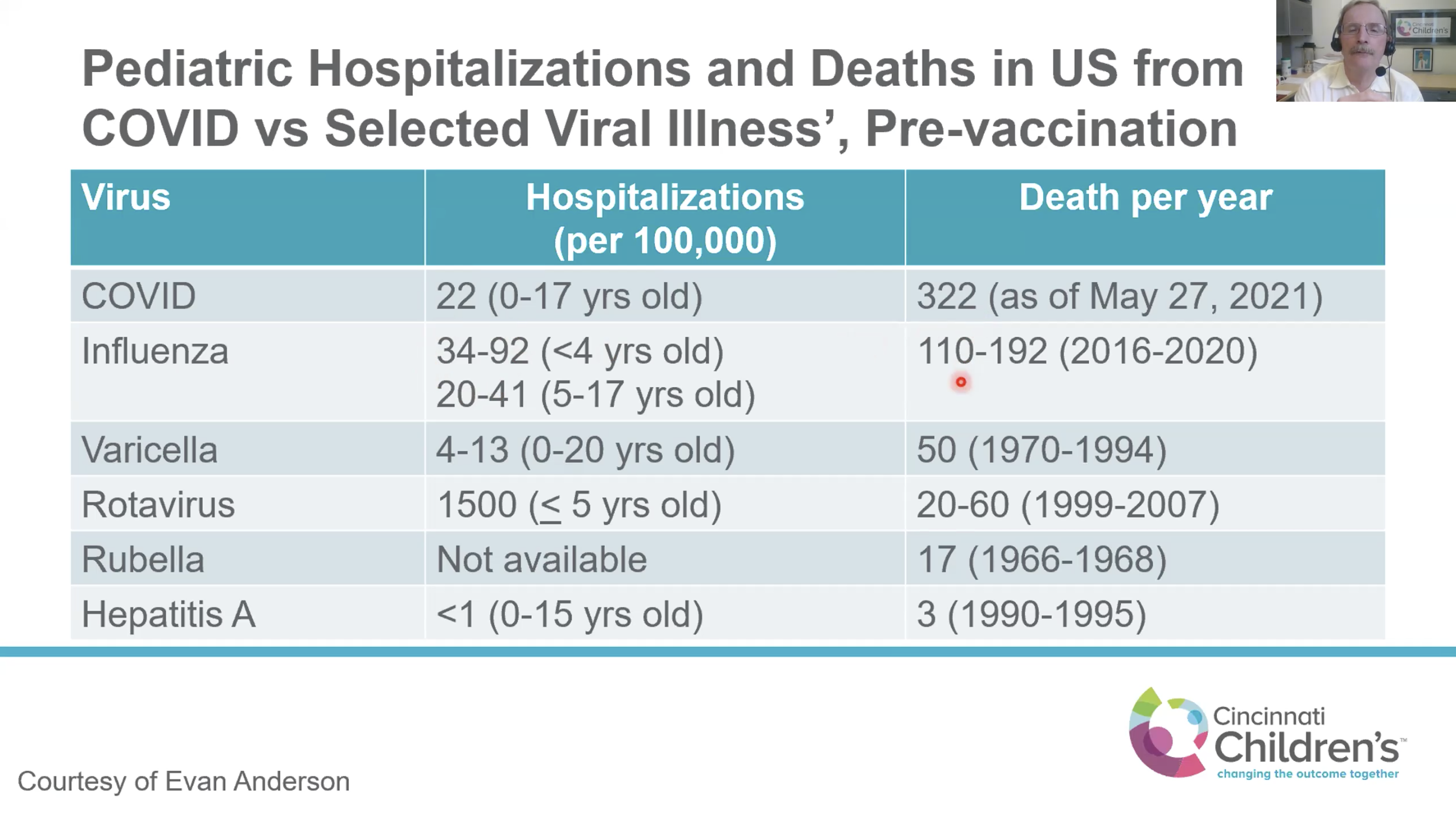

Of the nearly 4 million U.S. children who have tested positive for COVID-19 since the onset of the pandemic, 322 have died from the virus.

“These are perfectly normal, healthy kids,” he noted. “Beyond the deaths, the pandemic has also taken a significant toll on children’s mental and emotional health, social well-being, and educational experiences.”

Indirectly, vaccinating children can help others. For example, children are known to be good spreaders of other respiratory viruses, such as influenza.

“If you can block the infection in children, I really think that will block transmission to adults,” he said.

Frenck shared a chart comparing hospitalizations per 100,000 and deaths per year for select viral illnesses that can be controlled with vaccines, such as influenza, varicella, rotavirus, rubella, and hepatitis A. The chart showed that COVID is in the same range as influenza for hospitalizations, but the rate of death is nearly double or triple the rate for influenza in a typical year.

“The point here is that we’re vaccinating routinely against these viruses and others that cause much less morbidity and mortality than COVID,” he said.

WHAT DO THE COVID-19 PEDIATRIC AND ADOLESCENT CLINICAL TRIALS SHOW?

Frenck reviewed information from the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 adolescent clinical trials, including the trial process, efficacy rates, and adverse event reporting.

“The adverse event profile of the 12-to-15-year old’s is basically superimposable on the 16-to-25-year old’s, with the most common things being fatigue, headache, and chills,” he said.

Both vaccine trials demonstrated 100% efficacy in these adolescent age groups.

AstraZeneca, Janssen, and Novavax also are evaluating adolescent and pediatric expansions for their COVID-19 vaccine trials.

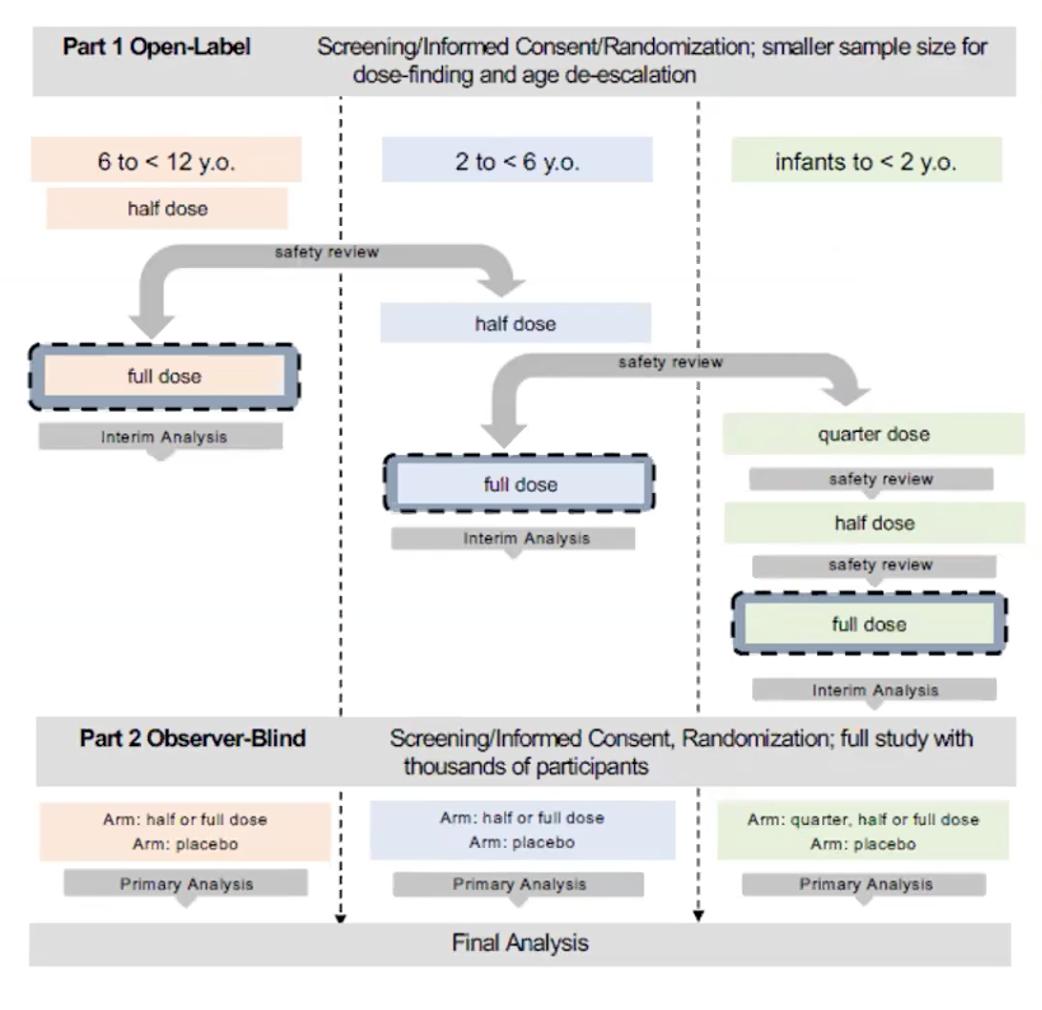

Frenck continued by reviewing information from the Pfizer and Moderna pediatric clinical trials for children under 12 years of age.

He shared a shell protocol that he and Spearman proposed to pharmaceutical manufacturers and was adopted for their current clinical trials.

During the seminar’s question-and-answer segment, Spearman reassured viewers that even though the protocol extends the length of the trial due to age de-escalation and dose finding, it ultimately won’t take any longer to fully vaccinate children, once the vaccine is approved or authorized.

More options for children are coming. Pfizer’s COVID-19 vaccine is now available for children 12 years and older. On June 10, Moderna filed for Emergency Use Authorization for its adolescent vaccine. Frenck predicted that vaccines for children younger than age 12 may be available by the end of 2021 or early 2022.