Another Puzzle Piece Found for Diagnosing Rare Liver Disease in Infants

Research By: Alexander Miethke, MD | Chunyue Yin, PhD

Post Date: March 23, 2021 | Publish Date: March 23, 2021

Rare Disease Detectives at Cincinnati Children’s Use Whole-Exome Screening to Discover a Gene Variant that Disrupts Healthy Bile Duct Formation in the Liver

The medical mystery began with a sick little girl from the Middle East, now aged 9. She was one of four children with unexplained cases of liver disease who had been referred to Cincinnati Children’s in hopes of finding answers.

This child’s journey started with seizures and bruising at 6 months of age, which doctors quickly suspected were symptoms of a liver malfunction. By her first birthday, she was enduring severe bouts of itching (another telltale sign of liver disease), along with vitamin deficiency and an enlarged liver.

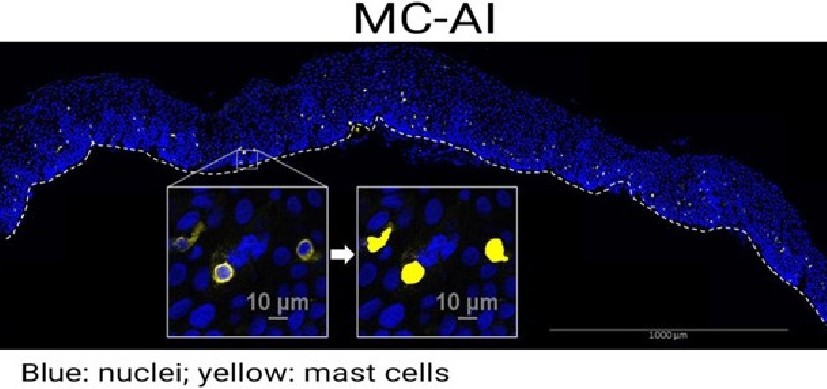

Further blood testing found highly elevated levels of bile acids and other indicators of an unhealthy liver. Then, a biopsy revealed that about half of her liver’s bile ducts did not form properly.

So far, doctors have managed the girl’s symptoms, including using three medications to reduce her itching and fortifying her diet to address malabsorption. At age 9, her liver was functioning well enough to not require a liver transplant.

The question facing the research team at Cincinnati Children’s was what could have caused this bile duct paucity? The answer was the discovery of a novel gene variant that appears to help explain at least a few more of the many unexplained cases of inherited liver disease affecting newborns.

Their findings were published online March 23, 2021, in the journal Gastroenterology.

One Organ. Multiple Disease Possibilities

The numbers of children born with liver disease are low, but for those children there’s a laundry list of a possible disorders to consider. Some of those conditions have been linked to specific genetic variants, such as progressive familial intrahepatic cholestasis (PFIC) type 1-4 or Alagille syndromes. Other cases remain unexplained.

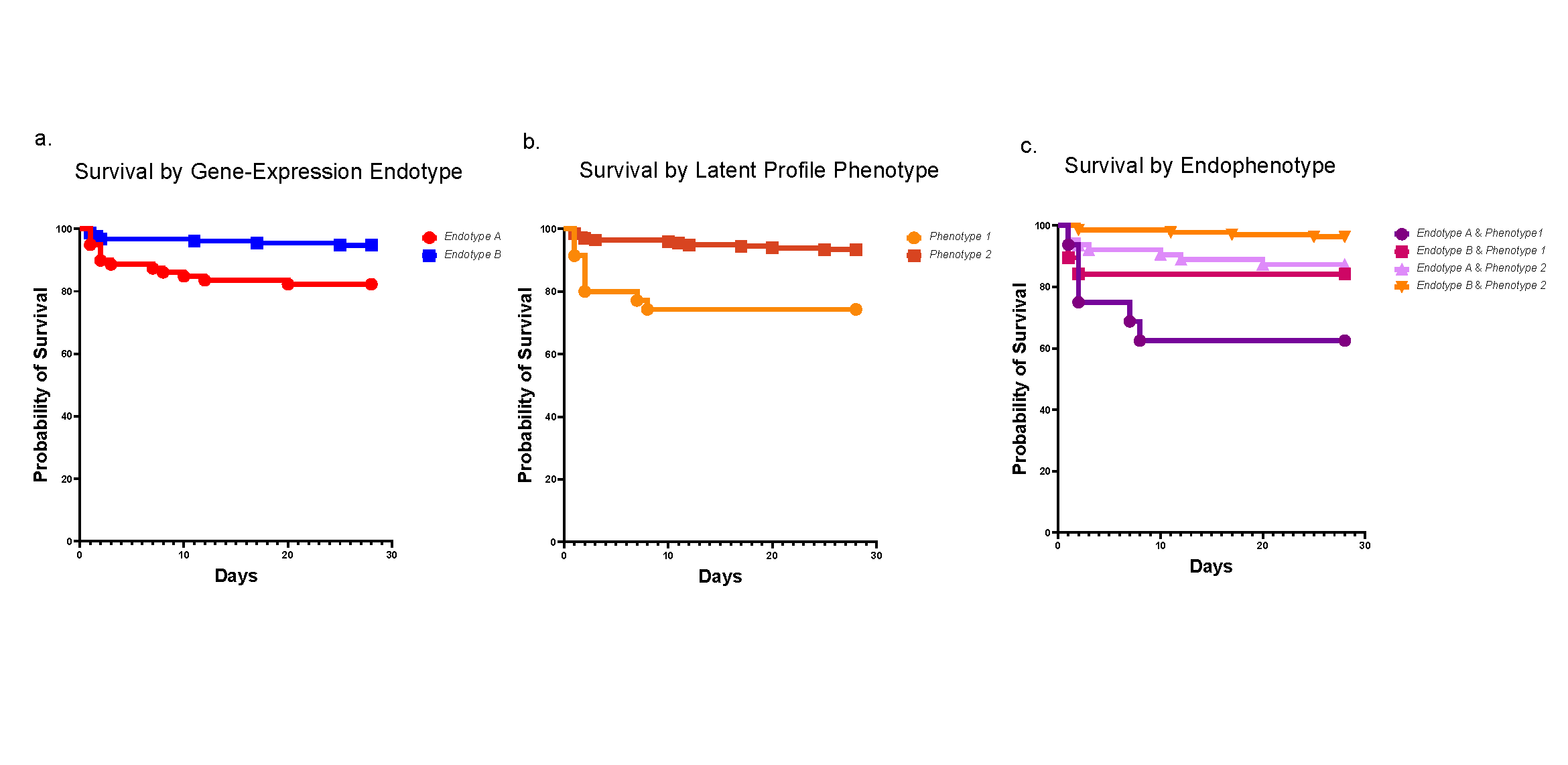

To find out more, the research team headed by Alexander Miethke, MD, and Chunyue Yin, PhD, conducted whole-exome screens on the first four patients. Three were found to have gene signatures that fit other conditions (PFIC 2 and 4), but the young girl appeared to have a unique gene variant that did not match any other known genetic cause of liver disease.

Her variant involved the gene ABCC12, which produces a protein called MRP9. In her case, her liver was not producing enough of this protein. It appeared that the gene variant might be responsible for the paucity of her bile ducts, but confirming the theory would require a deep dive into the basics of liver function.

From zebrafish to mice to humans

The research team initially used zebrafish to confirm that knocking out the ABCC12 gene shuts down MRP9 protein production and disrupts bile duct function in the fish. Then another long set of experiments confirmed the same genetic pathway to liver disease occurs in mice.

But does the same mechanism occur in humans?

To find out, the team collected samples from another 89 children who had previously been found to have unexplained liver disease with similar characteristics as the “index case” detected in the young girl. Using more-targeted methods than whole-exome screening, the team found five more children who also had rare variants in the ABCC12 gene.

“We show that loss of the gene in the index patient, and in mouse and zebrafish model organisms, was associated with a lower number of bile ducts—all of which occur inside the liver,” Miethke says. “We have found no evidence so far that this variant has an effect on the large bile duct outside the liver.”

Longer Term Implications

This is the first finding to show that ABCC12 has a role in controlling cholangiocyte health—the cells that form bile ducts, Miethke says.

This finding is important for children with liver disease and jaundice because the genetic basis of their liver and biliary tract abnormalities remain unknown in up to 50% of patients. It remains unclear exactly how many more children might have this novel genetic cause, but by adding this gene to existing screening panels, it eventually will be easier for doctors to establish a diagnosis for more children.

“In inherited liver disease, there is often a journey from center to center to make the diagnosis. This may help some patients reach a diagnosis earlier in that journey,” Miethke says. “But we are just in the beginning to exploring the role of ABCC12 for human health. It is possible that ABCC12 is a therapeutic target in children and adults who suffer from bile duct loss not for genetic reasons, but because of drug-induced liver injury, graft-versus-host disease, or primary sclerosing cholangitis.”

Having a more precise diagnosis suggests the possibility of more precise treatment. But much more study is required to determine the safest ways to intervene. In some cases, a child’s condition might be linked to deficiencies in the gene’s activity; more work is needed to find ways to compensate for the loss in function of MRP9. In other cases, such as a rare form of liver cancer called cholangiocarcinoma, it might be beneficial to inactivate the gene to induce cell death.

Looking ahead, the study further demonstrates the value of another useful tool for research.

“The zebrafish is a great animal model for drug screening,” says Yin. “With this finding, it is possible to perform drug screens on MRP9-deficient zebrafish to look for therapeutics for patients with defects in this protein.”

About this study

Authors from Cincinnati Children’s included co-first authors Duc-Hung Pham, PhD, and Ramesh Kudira, PhD, from the Division of Gastroenterology, Hepatology and Nutrition; and co-authors, Jillian Ellis, MS, Tiffany Shi, MS, Immaculeta Osuji, MS, Nelson Matuschek, MS, Liva Pfuhler, Student, Mary Mullen, PhD, and Sujit Mohanty, PhD.

Contributors included researchers from Shengjing Hospital of China Medical University, Aperiomics, Inc., Sterling, Va.; the Department of Pathology and Huntsman Cancer Institute, University of Utah; the Liver Center Laboratory at the University of California San Francisco; Mount Sinai Genomics, New York; and the Prince Sultan Military Medical City, Riyadh, Saudi Arabia.

Funding sources for this work included a pilot grant from the Center for Pediatric Genomics at Cincinnati Children’s, the National Institutes of Health (U01 DK62497, R01 DK095001, R01 DK117266-01A1, R01 CA222570, R01 DK094828); the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (P30 DK078392); The NIDDK’s Childhood Liver Disease Research Network; the American Gastroenterological Association; and the Center for Autoimmune Liver Disease at Cincinnati Children’s.

| Original title: | Deleterious variants in ABCC12 are detected in idiopathic chronic cholestasis and cause progressive cholangiocyte loss in model organisms |

| Published in: | Gastroenterology |

| Publish date: | March 23, 2021 |

Research By