Airborne Lead Exposure in Childhood Linked to Behavioral Problems in Adolescence

Research By: Erika Rasnick, MS | Cole Brokamp, PhD

Post Date: March 24, 2021 | Publish Date: April 2021

Since the removal of lead from gasoline, lead concentrations in the air around us have sharply declined. However, in most urban areas, lead is still detectable in ambient air. As children breathe in this air—at home, outside, along the bus route—could negative effects emerge later in life?

Using statistical methods, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s investigated how the timing of airborne lead exposure throughout childhood can impact behavioral health. Even at very low concentrations, the team associated this exposure with poor behavioral outcomes in adolescence, as published in the journal Environmental Epidemiology.

How Kids Can Be Affected

For decades, research has shown that elevated blood lead levels in childhood can lead to adverse neurobehavioral outcomes, even when these levels are below the reference value set by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). The negative effects are wide-ranging—from increased hyperactivity and decreased cognitive abilities in childhood, to increased rates of arrests for violent crimes and decreased gray matter volume in mood-regulating and decision-making regions of the brain in adulthood.

While most lead research focuses on blood levels, this is only one part of the picture. Blood levels are most representative of lead that is ingested, often from lead-based paint or contaminated water. Inhalation is still a concern—industrial emissions, transportation, and resuspended soil can cause airborne lead exposure.

“There is growing evidence that even very low levels of exposure can have neurotoxic effects, especially in children since their brains are actively developing,” says lead author Erika Rasnick, MS, of the Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology. “We were interested in ambient airborne lead because so much of the population is exposed to these low levels.”

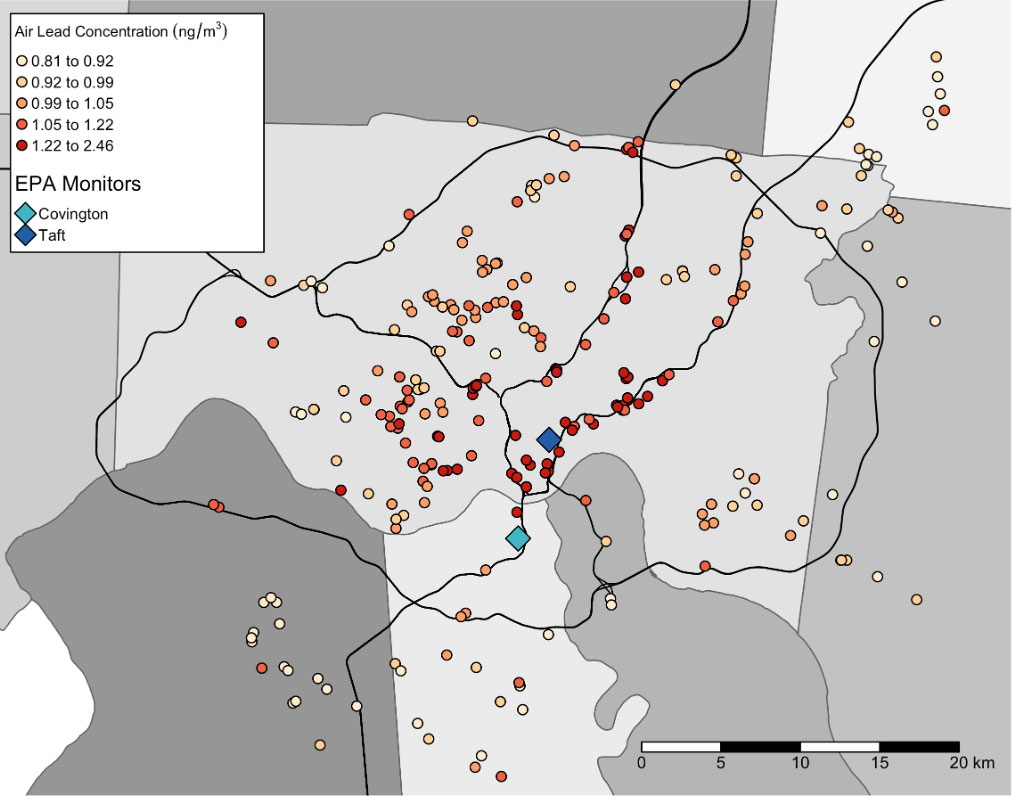

Researchers began by examining data from 263 children in the Cincinnati Childhood Allergy and Air Pollution Study. Using temporally scaled predictions from a validated land use model, the team estimated each child’s monthly air lead exposure. Parent-completed behavioral assessments offered insights on neurobehavioral outcomes at age 12. When the team combined this data with a distributed lag model, patterns began to emerge.

Why Timing Matters

Although the children in the study were never exposed to airborne lead levels above the United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) standard, resulting data revealed sensitive developmental windows when these low levels can have concerning effects on mental health.

When airborne lead exposure increased—even by small increments—behavioral problems were on the rise. The team found that lead exposure immediately following birth was associated with increased aggression and attention problems. When lead exposure occurred in mid- and late childhood, anxiety and atypicality scores increased.

As a child’s brain progresses through different stages of development, they are more vulnerable to the neurotoxic effects of lead exposure when compared to adults. By identifying these windows of vulnerability, researchers can better understand the relationship between ambient lead exposure and neurobehavioral problems.

The size of the population that is exposed to airborne lead makes the implications of this relationship far-reaching. Small increases in airborne lead concentrations could cause significant numbers of children to become at risk for neurobehavioral problems, leading to concerning trends in public health.

How Research Can Make a Difference

Among the first to examine associations between airborne lead exposure and child behavioral outcomes, this study highlights the need to reevaluate how we classify safe levels of ambient lead exposure. Data showed that when increases of exposure were associated with behavioral problems, levels were still low—ten times lower than the EPA standard.

“Most people aren’t concerned with their airborne lead exposure, since levels are so much lower than the standard,” says Rasnick. “However, our research may raise awareness that these low levels could be affecting children’s behavioral health, especially when exposed during certain time periods.”

While this study focused exclusively on children in the Greater Cincinnati region, the results could possibly apply to many areas of the United States with low levels of ambient lead.

“Lead in the air comes from many different sources, including local, regional, and national sources that are both mobile and stationary, which makes its concentration vary highly over space and time,” says Rasnick. “Given that there is no ‘safe’ level of lead, concerning levels of lead could be potentially occurring everywhere.”

Next, researchers plan to replicate this study with a larger cohort and wider array of participant data. Using statistical methods to study exposures over time, the team aims to further investigate underlying mechanisms.

More air pollution-related research

Air Pollution Linked to Mental Health Issues in Children

$5M Grant to Support Exploring Link Between Air Pollution and Mental Health

High Air Pollution Exposure Linked to Structural Brain Changes in Children

Air Pollution Linked to Spikes in Psychiatric Emergency Visits

About the Study

In addition to Rasnick, co-authors included researchers from Cincinnati Children’s Divisions of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, and General and Community Pediatrics.

Contributors also included researchers with Miami University, the University of Cincinnati, New York State Department of Health, University at Albany, and Simon Fraser University.

This work was supported by grants 5R01ES011170 and R01ES019890 from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences.

| Original title: | Identifying sensitive windows of airborne lead exposure associated with behavioral outcomes at age 12 |

| Published in: | Environmental Epidemiology |

| Publish date: | April 2021 |

Research By