Air Pollution, Racial Disparities and COVID-19 Mortality

Research By: Eric Brandt, PhD | Andrew Beck, MD, MPH | Tesfaye Mersha, PhD

Post Date: May 8, 2020 | Publish Date: May 7, 2020

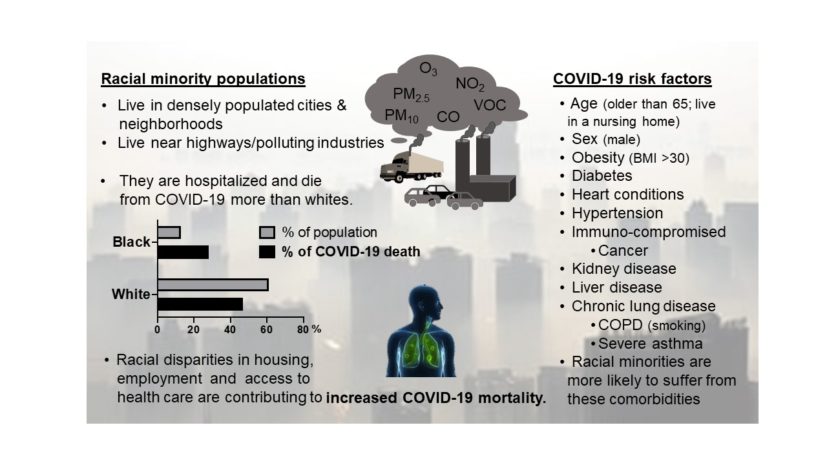

Because of long-standing structural racism and disparate experience with a range of socioeconomic and environmental factors, African Americans are at higher risk of dying from COVID-19 and many other health conditions, all worsened by chronic exposure to air pollution.

As scientists worldwide race to gather data about the novel coronavirus, one of the more surprising findings has been detecting the virus attached to fine particles of air pollution. This discovery has significant implications for often-marginalized populations living in high-density, high-smog conditions, according to experts at Cincinnati Children’s.

In a publication appearing online May 7, 2020, in the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, co-authors Eric Brandt, PhD, Andrew Beck, MD, MPH, and Tesfaye Mersha, PhD, explore a potential reason why African-Americans and other minorities have been suffering from COVID-19 at disproportionate rates.

Years of research have proven that ultrafine air pollution particles (PM 2.5) can cross into the blood stream and accumulate in tissues over a lifetime, the co-authors say. A recent study, published as a non-peer-reviewed pre-print, has even reported detecting SARS-CoV-2 virus attached to particles of air pollution.

This exposure, combined with cumulative lung damage caused by years of breathing polluted air, and prevalence of underlying comorbid illnesses, may explain why observers have reported associations between air pollution exposure and increased mortality from COVID-19 in China, Italy, and now the U.S.

In the U.S., African American patients have been hospitalized and have been dying of COVID-19 at disproportionately high rates. Researchers at Cincinnati Children’s write that this outcome reflects long-standing health disparities driven by race-based structural differences in living conditions, socioeconomic opportunity, and more.

According to the recently created COVID-19–Associated Hospitalization Surveillance Network (COVID-NET), compared with white Americans, black Americans on average have a three-fold higher infection rate and a six-fold higher death rate from COVID-19.

- Early data from Michigan suggest that 33% of COVID-19 cases and 40% of deaths were experienced by African Americans even though they represent just 14% of the state population.

- In Chicago, more than 50% of COVID-19 cases and nearly 70% of COVID-19 deaths involve black individuals, although blacks make up only 30% of the population.

- In Louisiana, 71% of deaths have occurred among black persons, who represent 32% of the state’s population.

- In Ohio, 20% confirmed cases are blacks, who represent 12% of the state’s population.

- In New York City, blacks and Hispanics accounted for 28% and 34% of deaths with population representation of 22% and 29%, respectively.

Within New York City, the number of patients with COVID-19 who were hospitalized and deaths per 100 000 population were highest in the Bronx and lowest in Manhattan.

“Further research is required to delineate the specific mechanistic link between severe outcomes from SARS-CoV-2 infection and low-income communities who are exposed to disproportionally polluted environments may contribute to and exacerbate disparities in COVID-19-related outcomes,” the co-authors state. “The ongoing strategies for mitigating the COVID-19 pandemic should focus on minimizing disparities in our healthcare system without forgetting the importance of mitigating air pollution in densely populated urban centers where more susceptible populations reside.”

| Original title: | Air pollution, racial disparities and COVID-19 mortality |

| Published in: | Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology |

| Publish date: | May 7, 2020 |

Research By