5 Childhood Risk Factors Predict Risk of Adult Cardiovascular Events

Research By: Jessica Woo, MHSA, PhD | Elaine Urbina, MD, MS

Post Date: February 8, 2023 | Publish Date: May 19, 2022

Cardiologists, endocrinologists and others have suspected for years that soaring rates of childhood obesity, along with other unhealthy risk factors, posed bad news for the heart health of future adults. In fact, several studies led here at Cincinnati Children’s have documented alarming signs of arterial stiffness, cholesterol buildup and other metabolic and epigenetic changes occurring far too early in far too many children.

Now, a long-term, large-scale study conducted by the International Childhood Cardiovascular Consortium (i3C) has confirmed a clear link between five childhood risk factors and the likelihood of adult cardiovascular events. Importantly, children did not have to be extremely obese to face elevated risks later in their lives.

Details were presented April 4, 2022, at the American College of Cardiology annual meeting and simultaneously published in the New England Journal of Medicine. Jessica Woo, MHSA, PhD, Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, served as corresponding author. Elaine Urbina, MD, MS, director of Preventive Cardiology at the Heart Institute at Cincinnati Children’s, was a senior co-author.

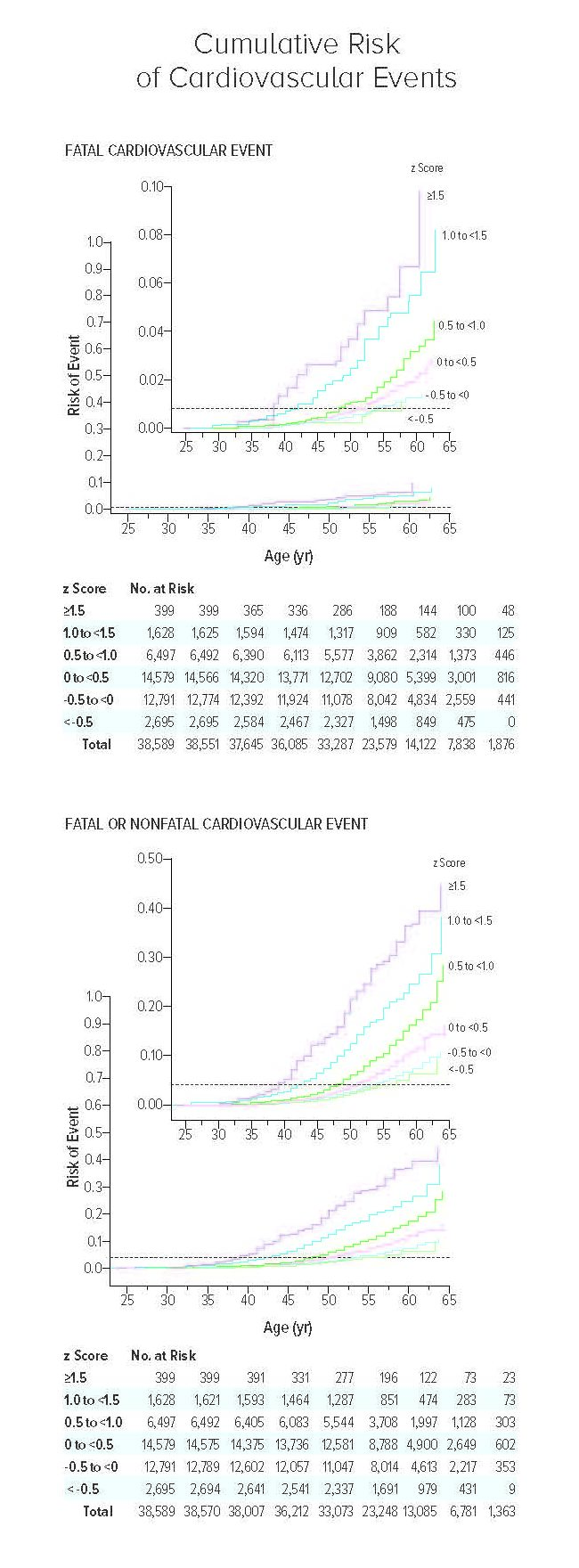

The study involved 38,589 participants from Australia, Finland, and the US, who were followed from age 3-19 years for a period of 35-50 years. The team found that five risk factors, individually or in combination, present in childhood were predictors of fatal and non-fatal cardiovascular events.

These risk factors were detected in over half the children studied—and for some, the risk was nine times higher than those with below-average risk factors. Especially concerning, 75% of the strokes and heart attacks occurring in the higher-risk study participants people occurred before age 53. While most survived their initial events, more than 300 died.

“These findings are remarkable in demonstrating that children with only mildly elevated body mass index, blood pressure or lipids, and youth who start smoking, may be at higher risk for adult cardiovascular disease,” Woo says. “However, we also show that when these risk factors are lower in adulthood than in childhood, for example quitting smoking between childhood and adulthood, the risk of suffering from adult cardiovascular disease was lower. This highlights the importance of ensuring that all children develop and maintain healthy habits into adulthood.”

FIVE PREDICTIVE RISK FACTORS

The study whittled a host of possible risk factors down to a combined “z score” based on five risk factors with statistically significant importance. Overall, each 1-point increase in the z score measured during childhood was associated with a 2.71- to 3.54-fold higher likelihood of death from adult cardiovascular events:

- For total cholesterol: 1.30 (95% CI 1.14-1.47)

- For BMI: 1.44 (95% CI 1.33-1.57)

- For systolic blood pressure: 1.34

(95% CI 1.19-1.50) - For triglycerides: 1.50 (95% CI 1.33-1.70)

- For smoking: 1.61 (95% CI 1.21-2.13)

“Much evidence suggests that the seeds of cardiovascular disease are in childhood, but the specific evidence linking childhood measurements to clinical disease was absent until our study,” says co-first author David Jacobs, Jr., PhD, Division of Epidemiology and Community Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School. “This study is remarkable in that we now have that evidence and we found it by following participants from childhood to adulthood over many decades.”

In an editorial published alongside the study, NEJM deputy editor Julie Ingelfinger, MD, of the Mass General Hospital for Children in Boston, wrote that the findings mark a “coming of age” for robust clinical cohorts that finally provided once-elusive evidence connecting childhood risks to adult outcomes.

The cumulative risk of cardiovascular events is shown as the estimated probability according to the combined-risk z score and age (Kaplan–Meier method). The horizontal dashed line in each panel indicates the overall risk of the event. Top panel shows the hazard ratios for fatal cardiovascular events, and bottom panel shows the hazard ratios for fatal or nonfatal cardiovascular events. All participants were included in these analyses; there were 319 fatal events and a mean of 1,563 fatal or nonfatal events across imputations. In each panel, the inset shows the same data on an enlarged y-axis.

“If CV risk factors can be identified early in life, we as clinicians have opportunities to address health issues early and might uncouple risk from an inexorable march toward CVD and death,” Ingelfinger wrote. “We have been waiting for hard data showing that risk factors seen in childhood forecast future disease, and now we have a good start concerning CVD.”

“More than 126 million people worldwide are affected every year by cardiovascular disease. This is the leading cause of death in the United States and throughout the world,” Urbina says. “Unfortunately, few maintain the ideal cardiovascular health that nearly all children have at birth.”

NEXT STEPS: START PREVENTIVE MESSAGING EVEN EARLIER

Each of the five factors called out in the study can be enough by itself to drive cardiovascular risk, but frequently, these factors co-exist for individuals to build even higher combined, cumulative risk scores. This suggests that programs to reduce risk should not wait until adulthood begins, although many do.

Routine heart health testing may need to start at earlier ages than most families would expect, Urbina says. Also, the sheer frequency of children already coping with one or more heart health risk factors suggests a need for wide-ranging public health preventive strategies.

It may not be enough to encourage exercise and healthy eating on their own. It may not be effective to treat concerns about childhood smoking or vaping as a siloed issue.

“More research is needed to understand what preventive strategies can be scaled up enough to make an impact,” says Urbina.

Meanwhile, research continues to develop tools to more precisely identify children at highest risk. These children may need interventions previously reserved for adults, including medications, bariatric surgery, cognitive behavior therapy or other interventions.

For example, few cardiac medications have been studied for safety and efficacy in children. Long-term impacts of other treatments and interventions also remain under-studied.

“Our next step is to refine our risk score by adding genetic factors and social determinants of health,” says Woo.

Read the 2022 Research Annual Report

ABOUT THE STUDY

In addition to researchers from Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati, this study involved collaborators from the University of Minnesota, the University of Colorado, Children’s Hospital Colorado, the University of Turku and Turku University Hospital in Finland, Tampere University in Finland, the University of Tasmania in Australia, Tulane University, the University of Iowa, Wake Forest School of Medicine, Murdoch Children’s Research Institute in Australia, and the University of Oxford in the United Kingdom.

| Original title: | Childhood Cardiovascular Risk Factors and Adult Cardiovascular Events |

| Published in: | The New England Journal of Medicine |

| Publish date: | May 19, 2022 |

Research By

The overarching theme of the Woo Lab is to understand the causes and short- and long-term consequences of childhood obesity and metabolic dysregulation.

My area of expertise is non-invasive imaging of the heart and blood vessels in youth with risk factors for heart attack and stroke.