3D Printed Hearts Helping Cincinnati Children’s Cardiologists Plan Complex Heart Surgeries

Post Date: June 27, 2019 | Publish Date: Feb. 20, 2015

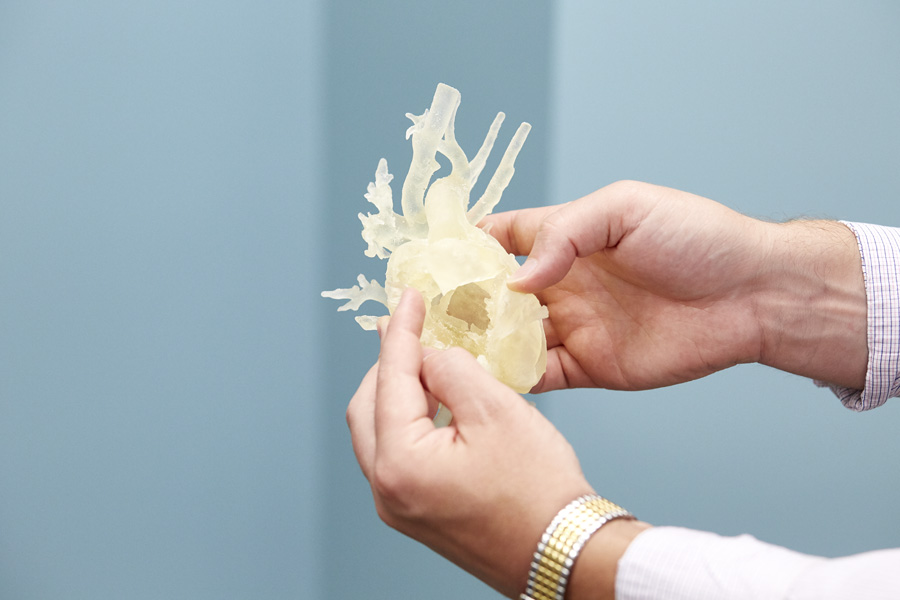

When Damon Mallott was born in 1984, it took innovative surgical techniques to correct his complex heart defects. Thirty-one years later, cardiothoracic surgeons at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center have again innovated to keep Damon alive, this time by first simulating an extraordinarily complex heart surgery on a 3D model of Damon’s heart.

After decades of living with his repaired heart, Damon began having heart rhythm abnormalities (arrhythmias) as well as blood clots that could have traveled to his lungs or caused a stroke. His doctors and surgeons recommended that he undergo a complicated procedure to avoid the potential for heart failure. But the old repairs were unusual, and the new repairs quite risky.

Because the scale model of Damon’s heart showed the full scope of his cardiac anatomy in three dimensions, the surgical team at Cincinnati Children’s was able to plan the complicated procedure by first performing surgery on the 3D model.

“Planning made a huge difference in Damon’s surgery,” says Gruschen Veldtman, MD, Damon’s cardiologist at Cincinnati Children’s. “His old-style surgery is relatively rare nowadays. Planning eliminated surprises and gave us reassurance that Damon would get the best care. It helped turn complexity to simplicity and removed mystery from the equation.”

3D printing is a process of making three dimensional solid objects from a digital file. The patient-specific models of heart disease are constructed from MRI and CT scans. The creation of a 3D printed object is achieved by laying down successive layers of material until the entire object is created. Each of these layers can be seen as a thinly sliced horizontal cross-section of the eventual object.

“To me, this is the future – the next major step in imaging and pre-operative assessment of unique anatomical structures,” adds David Morales, MD, director of cardiothoracic surgery at Cincinnati Children’s. “Our imaging capabilities are excellent, but it’s not the same as being able to hold an exact model of the patient’s heart in your hand. This has changed our ability to truly visualize complex congenital heart disease prior to surgery to optimize outcomes.”

The heart has an electrical system that coordinates muscular contraction of the heart. Damon’s heart was prone to tachycardia, a faster than normal heart rate. Using the 3D model, the electrophysiology team at Cincinnati Children’s, which helps manage heart rhythms in patients, worked with Morales to plan the surgery. They helped identify where in Damon’s heart to form a sort of patchwork quilt, in which lines between sections of the quilt prevent abnormal rhythms from traveling throughout Damon’s heart.

Cincinnati Children’s cardiologists and surgeons have used more than 20 models of patients’ hearts in the last year to plan surgeries. In one instance, seeing the 3D version of a heart prior to surgery helped cardiologists and surgeons realize that resecting the large tumor in that heart would be too risky. In this case, they elected to do a series of ablations (removal of tissue) instead to help stop the electrical interference that was causing his heart to beat erratically.

The models are part of a research collaboration between Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati. Cincinnati Children’s provided a portion of the capital for the College of Engineering and Applied Science (CEAS) to purchase two new 3D printers. The advanced imaging group at Cincinnati Children’s, led by Michael Taylor, MD, performs the complex task of transforming standard MRI and CT images into 3D digital models that are transferred to the Digital Fabrication Lab at CEAS to be printed. For Damon’s model, Ryan Moore, MD, a cardiology fellow, created the digital model.

“The collaboration with Cincinnati Children’s has provided a great opportunity for future engineers from CEAS to facilitate the exciting work of the Heart Institute while simultaneously creating 3D models that help to support CEAS research,” says Sam Antoline, manager of the CEAS Digital Fabrication Lab.

Together, the institutions hope to determine how models affect decision-making, patient care and outcomes, communication among team members, and costs. In the meantime, Veldtman already is a believer. “I think this has added a good number of years to Damon’s life before he may need another procedure,” he says. “He is free from blood clots, and his heart is working more efficiently. He should have a better quality of life and a longer life.”

Additional information about Damon and 3D hearts can be found in a blog post written by Veldtman at http://wp.me/pFThB-4Dg