Teaming Up to Solve a Headache About Headaches

Post Date: July 3, 2019 | Publish Date: Spring 2019

“So now we’re going back to the bench and asking, ‘When we attempt a treatment, what parts of the brain are being affected?’ What mechanisms are involved? Why is the placebo effect so powerful?”

—Scott Powers, PhD

Clinicians describe chronic migraine as having at least 15 days per month of headache for more than three months with at least two aggravating symptoms. The pain tends to come with a pulsating quality. Sufferers often feel nausea, an aversion to light, or other discomfort severe enough to disrupt normal activity.

Nearly 2,000 children and teens visit the Headache Center at Cincinnati Children’s each year seeking help to relieve misery that often keeps them out of school, off the field and curled up in a dark room. Many families hope that doctors can simply prescribe a pill to make the pain stop. Many are surprised to find out that medications—especially by themselves—are not necessarily the right answer.

Experts in the field say a seismic shift is occurring in migraine pain management. While one surprisng study reports that two of the most frequently prescribed migraine medications show no better results than placebo, other studies suggest promising results from non-medication approaches such as cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT).

Now, a team of scientists at Cincinnati Children’s is working to learn more about why. They are combining expertise in brain imaging technology, neurology, behavioral therapy, and other fields to lay the foundation for a new set of best practices in migraine control.

Bringing varied skill sets to bear in the hunt for better solutions for migraine pain is no accident. Forging working partnerships from bench to bedside is a prime mission of the Mind Brain Behavior Collaborative, say co-leaders Lori Stark, PhD, Director of Behavioral Medicine and Clinical Psychology, and Tracy Glauser, MD, Associate Director of the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation.

“One of our strengths over the years has been our collaborative nature. But collaboration can either occur passively, or we can actively encourage and support collaboration by being a catalyst,” Glauser says. “The pain group is a perfect example of bringing medical providers, behavioral health providers, researchers, patients and families, all together in an active fashion to allow them to improve care and make discoveries.”

Moving Forward by Going Back to the Bench

A surprising study of teens with migraines, published in 2017 in The New England Journal of Medicine, helped spark a fundamental reexamination of pain treatment. The study, led by Cincinnati Children’s investigators Scott Powers, PhD, and Andrew Hershey, MD, PhD, reported finding no statistical difference between the two most-prescribed migraine medications—amitriptyline and topiramate—and placebo.

The study did not conclude that the medications offered no value. Instead, the co-authors reported that the expectation of benefit from taking any pill, including a placebo, was powerfully strong. The unexpected findings meant that scientists have much more work to do.

“So now we’re going back to the bench and asking, ‘When we attempt a treatment, what parts of the brain are being affected? What mechanisms are involved? Why is the placebo effect so powerful?” Powers says. “Then as we find those connections, we can design treatments that intentionally trigger those parts of the brain.”

Can Psychological Treatments for Pain be Imaged?

With the nation facing an epidemic of opioid abuse, safely and effectively managing pain has become a more complex challenge.

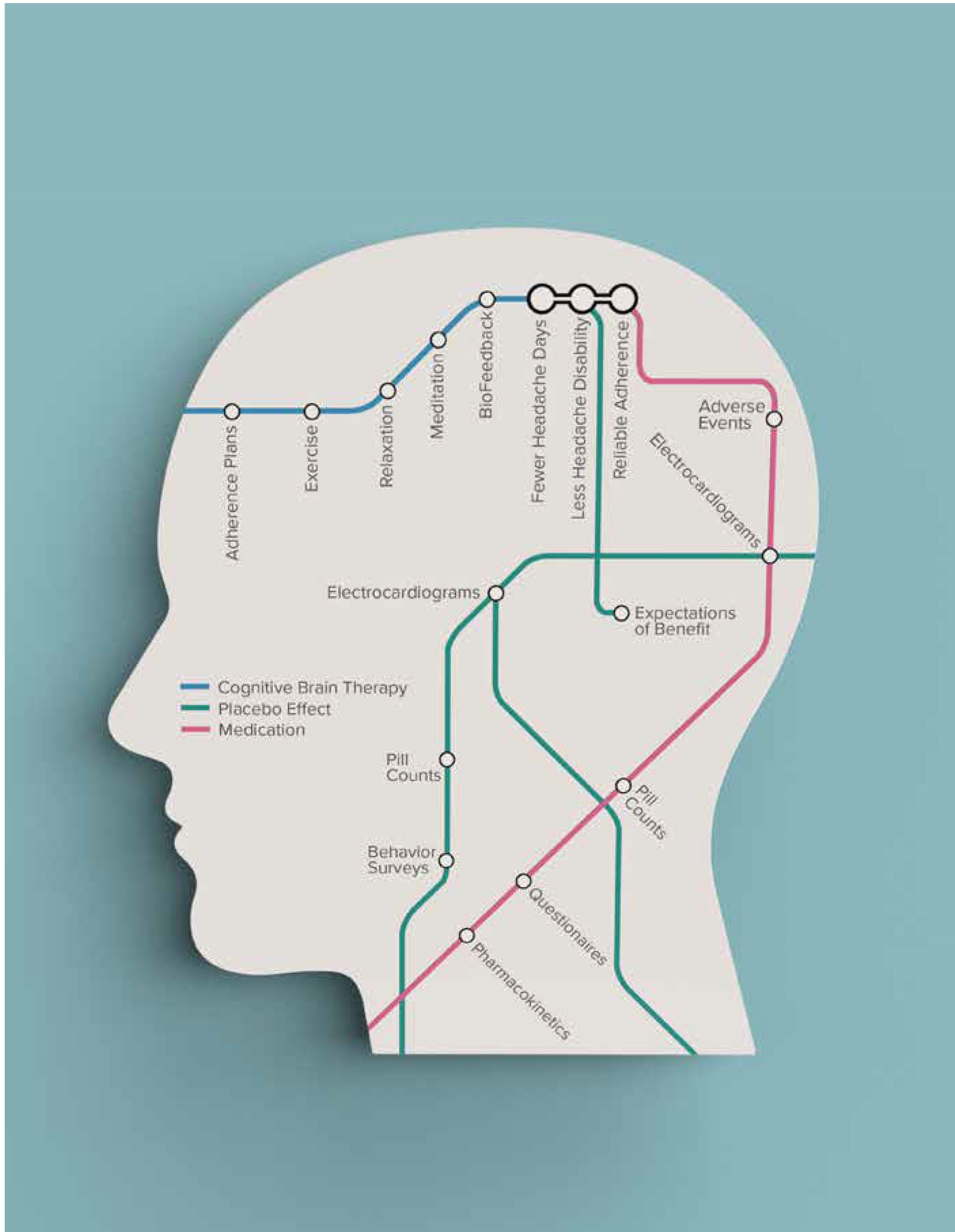

In previous research, Powers and colleagues have reported significant success in controlling migraine pain through cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT). Instead of medication, CBT components focus on cognitive modification and distraction, and behavioral change strategies such as relaxation training, biofeedback, activity pacing, and adherence plans.

Clinical trial data reported as far back as 2013 shows that CBT helps reduce headache frequency and disability. And yet, many physicians remain reluctant to trust CBT over medication. To some providers, if pain can be controlled without a pill, then maybe the pain isn’t real. With many young patients already facing doubts and questions about exaggerating their suffering, some tell doctors that having a prescription medication provides validation.

But what if CBT produces detectable, measurable changes in brain function? Robert Coghill, PhD, an expert in using brain imaging to study pain, has teamed up with Powers to use functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to determine how CBT influences brain activity and connectivity.

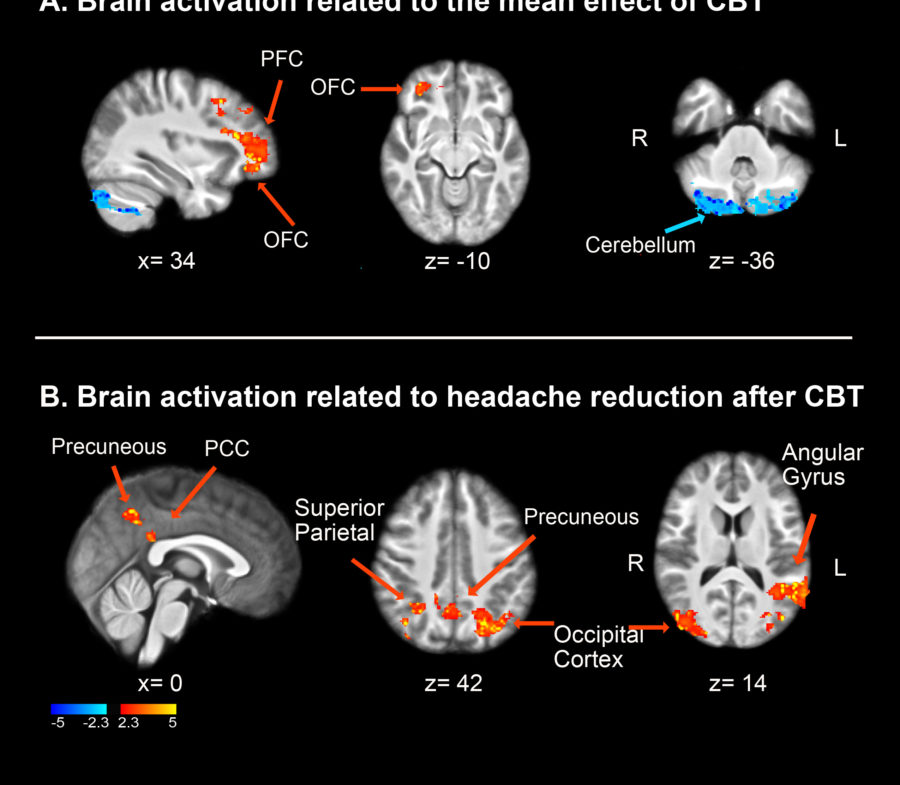

Coghill and Power’s pilot study is demonstrating real brain changes from CBT.

“Our preliminary data tell us kids who get more than eight migraine days a month see this reduced by 33 percent after they get cognitive behavioral therapy to teach them coping skills,” Coghill says. “Amazingly, fMRI data shows changes in the function of several regions of the brain in children who receive behavioral therapy.”

Regions including the prefrontal cortex, the posterior cingulate cortex and the precuneus showed the most significant increases in activation after CBT.

To study changes in brain connectivity, Coghill and Powers focused on the amygdala, a brain region thought to be the lynchpin for controlling the emotional-affective dimension of pain. So far, the study suggests that CBT helps control pain by changing interactions between the amygdala, the insular cortex and other regions that are important in the processing of pain.

Based on these early findings, Powers and Coghill have embarked on a full-scale study to directly compare brain changes produced by CBT with those produced by drug treatment in youth with migraine.

Stark sees enormous potential in the visual power of fMRI imagery to convince patients and families that treatments are making a difference.

“This technology can help in a number of ways,” Stark says. “It can help convince people that the pain a child feels is real. It also can show that a treatment that does not involve medication can affect the parts of the brain that can inhibit headaches just as much as a chemical can. Obtaining that kind of result is only possible through collaboration across disciplines.”

—By Tim Bonfield