Skin Keeps Time Independent of the Brain

Research By: Richard Lang, PhD

Post Date: October 17, 2019 | Publish Date: Oct. 10, 2019

The study is the first functional demonstration of opsin photoreceptors outside the eye directly controlling circadian rhythms in a mammal. The finding opens doors for using light to accelerate wound healing.

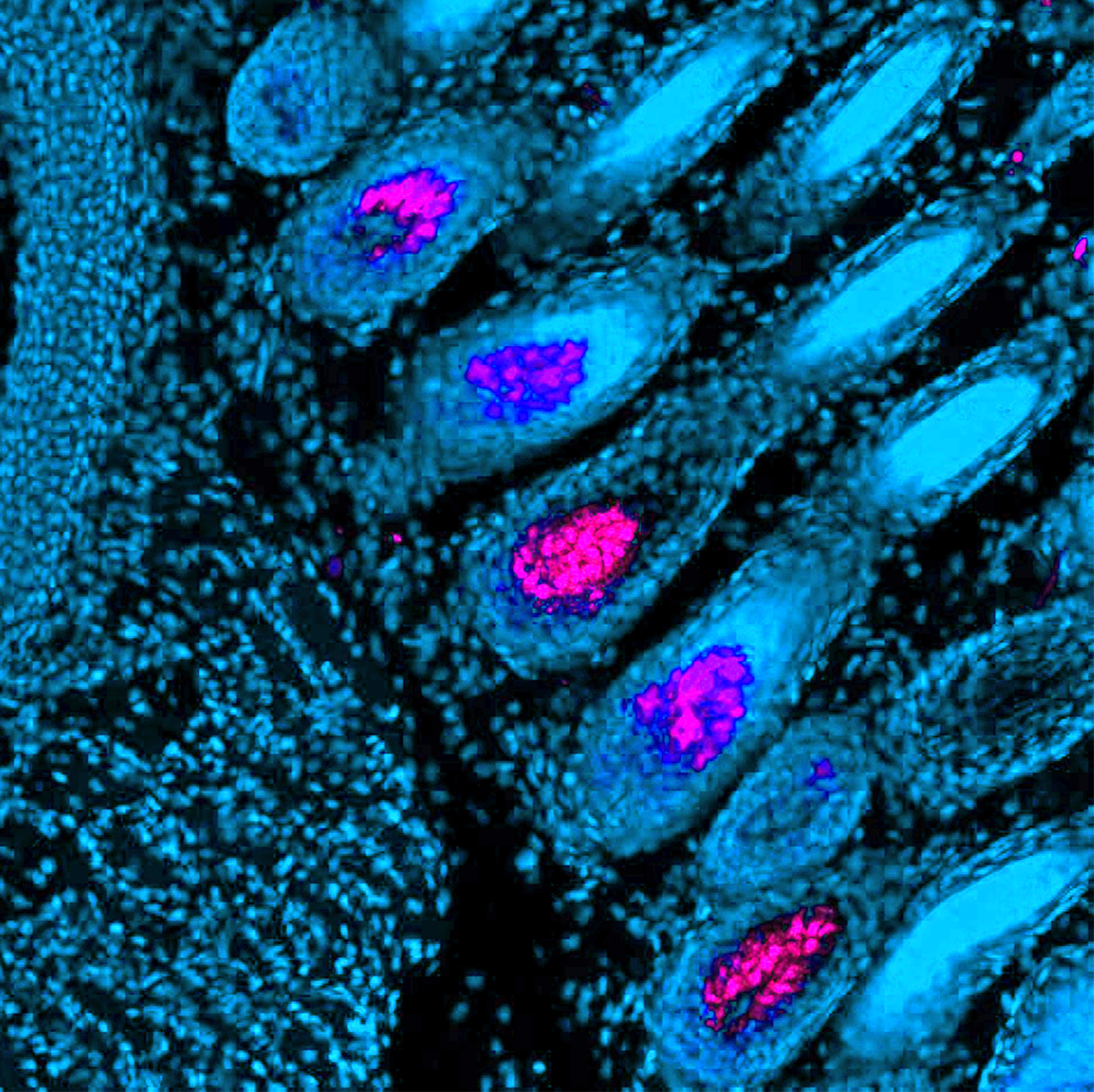

Skin expresses its own photoreceptors using a previously mysterious member of the opsin gene family, neuropsin.

Squids, octopuses, cuttlefish, amphibians, and chameleon lizards are among the animals that can change the color of their skin in a blink of an eye. They have photoreceptors in their skin that operate independently of their brain. The photoreceptors are part of a family of proteins known as opsins.

Mammals have opsins, too. They are the most abundant proteins in the retina. These light-sensing photopigments are responsible for color vision (cone opsins) and vision in dim light (rhodopsin). While previous studies have suggested that mammals might express opsin proteins outside the eye, there was little information on what functions they might influence.

A study from scientists at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Washington School of Medicine in published Oct. 10 in Current Biology now finds that a type of opsin known as neuropsin is expressed in the hair follicles of mice and synchronize the skin’s circadian clock to the light-dark cycle, independent of the eyes or brain.

“Although our research is still underway, we hypothesize that specific colors of light at certain times of day will influence how the skin heals,” said co-lead investigator Richard Lang, PhD, Division of Pediatric Ophthalmology at Cincinnati Children’s and Director of our Visual Systems Group. “The potential for using circadian rhythms to enhance medical practice is a growing field of study. Recent work has shown that the timing of medication administration at specific hours of the day or night can have a major influence on drug effectiveness. It is likely that this same observation applies to skin mediations.”

The study is the first functional demonstration of opsin photoreceptors outside the eye directly controlling circadian rhythms in a mammal, according to co-lead author Ethan Buhr, research assistant professor of ophthalmology at the University of Washington School of Medicine.

Buhr said it was assumed that, when mammals evolved, the brain took over informing all organs of the body if it was day or night. But, he said, this study found that the skin actually expresses its own photoreceptors using a previously mysterious member of the opsin gene family, neuroposin.

This means that skin can sense whether it is day or night even when it’s cultured by itself in a dish.

“If you simulate taking the cultured skin from Seattle to Japan (by simulating the light changes across time zones), the skin figures out that the time zone has changed and adapts to the new time zone within days because of neuropsin,” said co-author Russ Van Gelder, professor and chair of ophthalmology at the UW School of Medicine. .

The implications for medicine are still being investigated. Research from other laboratories has shown that important physiology in the skin is under control of the circadian clock. For example, work by Nobel Laureate Aziz Sancar’s group at University of North Carolina has shown that ultraviolet light given in the early morning had a five-fold higher effect in initiating skin cancer in mice, compared to the same light given in the late afternoon, because of circadian changes in the skin’s ability to repair DNA damage.

Researchers now want to see if skin heals better if it’s exposed to certain types of light.

In this study, the research team used mice with no retinal photoreceptors and a nonfunctional melanopsin gene. Normally, retinal photoreceptors combine with melanopsin to inform the brain’s circadian clock whether it is light or dark. Experimental mice were thus unable to synchronize their behavior to the light-dark cycle.

However, the circadian rhythms of these animals’ skin remained synchronized to the local light-dark cycle. Some mice were waking up at dawn, some at dusk. Mice normally run only at night, but some were starting to run on their wheels before it got dark. Regardless, the skin could use neuropsin to sense the light-dark cycle and keep time.

Read more about eye development research at Cincinnati Children’s

Learn about the Molecular and Developmental Biology graduate program at Cincinnati Children’s

| Original title: | Neuropsin (OPN5) Mediates Local Light-Dependent Induction of Circadian Clock Genes and Circadian Photoentrainment in Exposed Murine Skin |

| Published in: | Current Biology |

| Publish date: | Oct. 10, 2019 |

Research By