Not Just Individuals: Health System Hesitancies Also Increased COVID Risks

Research By: David Hartley, PhD, MPH | Andrew Beck, MD, MPH

Post Date: December 8, 2023 | Publish Date: Dec. 6, 2023

Experts at Cincinnati Children’s explore issues that need resolving before next public health crisis strikes

More than 1.2 million people have died in the United States during the COVID-19 pandemic to date, more documented deaths than any other nation on Earth.

While many have attributed the high death toll on widespread personal hesitancy to wear masks, avoid crowded places or receive vaccines once they were developed, there were several “system hesitancies” that contributed to the tragic outcomes that need addressing, according to an analysis published Dec. 6, 2023, in Health Affairs Forefront.

The analysis was written by first author David Hartley, PhD, MPH, and corresponding author Andrew Beck, MD, MPH, at Cincinnati Children’s. Co-authors included Peter Margolis, MD, PhD, and Robert Kahn, MD, MPH, from Cincinnati Children’s; Steve Miff, PhD, president and CEO at the Parkland Center for Clinical Innovation; Muhammad Zafar, MD, University of Cincinnati; Kate Schroder, president and CEO at Interact for Health in Cincinnati; Tiffany Mattingly, vice president, clinical strategies at The Health Collaborative in Cincinnati; and Pierre Barker, MD, MBChB, chief global partnerships and programs officer for the Institute for Healthcare Improvement in Boston.

“Such hesitancies continue to stand in our way, placing the public at risk for infection, hospitalization, and even death during times of uncertainty and danger. Moreover, disruptive effects of system hesitancies are not shared equally across populations, with disproportionate clinical and economic burdens for the elderly, communities of color, those living with poverty, and children who were forced to see a safe return to school politicized,” the co-authors state.

These systemic hesitancies included:

Hesitancy to comprehend and act on warnings

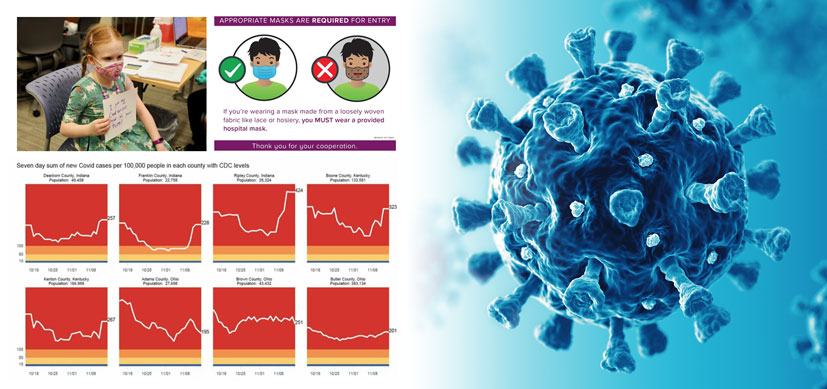

By February 2020, reports of COVID-19’s dire impacts on populations and health care systems around the world had circulated widely. But many politicians downplayed or contradicted calls to action from public health and medical professionals in ways that wasted precious time and limited the ability of health professionals to minimize morbidity and mortality.

Hesitancy to share, integrate, and learn from diverse data streams across sectors

Inflexible, outdated disease reporting systems resulted in chasms of disconnection in data sharing and collaboration from state to state and city to city across public health agencies, hospitals, nursing homes, group homes, jails, prisons, and other care centers. Often, privacy-related regulations and sensitivities made officials hesitant to share data, even when it was possible to do so.

Hesitancy to coordinate

Early in the pandemic, it took tremendous effort for organizations to work together to share limited supplies of personal protective equipment and to collaborate on how to manage patients who needed care. A lack of experience as collaborators, combined with competitive distrust, fears of negative media coverage, and other barriers magnified the impact of outbreaks occurring within single organizations.

Hesitancy to enable and empower local leadership

Early in the pandemic, the federal response emphasized political considerations that exacerbated partisan divisions, provoked confusion, and diminished trust in critical public health institutions. Later in the pandemic, some locales enacted legislation now limiting or preventing effective public health leadership.

Improvement remains possible

Newer technology has made near real-time disease surveillance possible on wide scales, but wider adoption is needed. Many lessons learned about coordinated response to natural disasters still can be translated to public health responses to disease outbreaks.

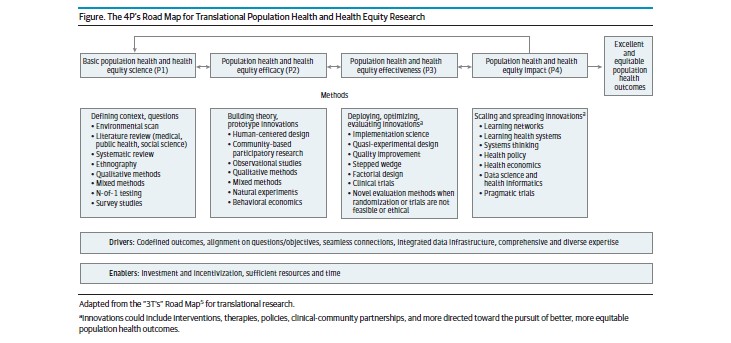

Looking forward, system improvements should not focus only on top-down command and control, but rather upon top-down and bottom-up organizational approaches that support flexible, adaptive, and timely responses, the co-authors say.

In previous research about COVID response, several of the co-authors on the Health Affairs Forefront article also co-authored a report in April 2021 in the Mayo Clinic Proceedings that described how a number of organizations collaborated in southwest Ohio to rapidly build a “regional learning health system” to respond to the pandemic.

In southwest Ohio, a history of routine meetings between otherwise disconnected and often competitive hospitals, health departments and other agencies helped cut red tape, speed data sharing, and smooth resource sharing when COVID struck. That experience may serve as a model for other communities, the co-authors suggest.

“We can design a resilient public health system resistant to hesitancies, a system capable of detecting dynamic public health emergencies, and responding nimbly and efficiently,” the co-authors say. “To do so, we need an integrated system that works across sectors, approaches leadership in a new way, and enables rapid learning from the top-down and bottom-up.”

| Original title: | Learning From COVID-19 To Overcome System Hesitancies In Public Health Preparedness And Response |

| Published in: | Health Affairs Forefront |

| Publish date: | Dec. 6, 2023 |

Research By

My research focuses on infectious disease epidemiology, public health surveillance, and mathematical and computer modeling.

I help lead Cincinnati Children’s community health initiative which seeks to equitably optimize child health outcomes.