Neighborhood Poverty, Public Insurance Status Outweigh Race for Risk of Diabetes-Related Hospitalization

Research By: Andrea Maxwell, MD | Nana-Hawa Yayah Jones, MD |

Post Date: September 28, 2021 | Publish Date: Aug. 18, 2021

“Interventions that address neighborhood poverty and/or mitigate family-level risks associated with that poverty could have a large effect on reducing preventable DKA hospitalizations.”

—Andrea Maxwell, MD

For children with type 1 diabetes (T1D) and their caregivers, potential complications are an ever-present concern. When it comes to mitigating these risks, some actionable factors can help, such as regular blood glucose monitoring and insulin administration.

However, a new study suggests that socioeconomic factors could also play a major role in outcomes of T1D. In a study published August 18 in the Journal of Hospital Medicine, researchers at Cincinnati Children’s found that children living in high-poverty areas or on public insurance are significantly more likely to be admitted to the hospital for diabetic ketoacidosis (DKA).

DKA is a life-threatening condition that develops when the body can’t produce enough insulin and begins to break down fat as fuel. This process causes a buildup of acids in the bloodstream called ketones. Without prompt treatment, DKA can lead to loss of consciousness and eventually death.

While all children with T1D and their caregivers face the possibility of DKA, this study shows that the burden is not equally distributed. Understanding the risk factors associated with DKA and why these disparities emerge could help improve outcomes.

“Our research was inspired by Dr. Nana-Hawa Yayah Jones’ work with patients who have a diagnosis of T1D,” says Andrea Maxwell, MD, assistant professor at the Medical College of Wisconsin and recent graduate of the Academic Research Fellowship in Pediatric Critical Care at Cincinnati Children’s. “Those who identified as Black race and those of lower socioeconomic status had worse outcomes than those who identified as White and those of higher socioeconomic status. We wanted to examine these potential disparities in detail so that future interventions could be focused on narrowing—or eliminating—equity gaps.”

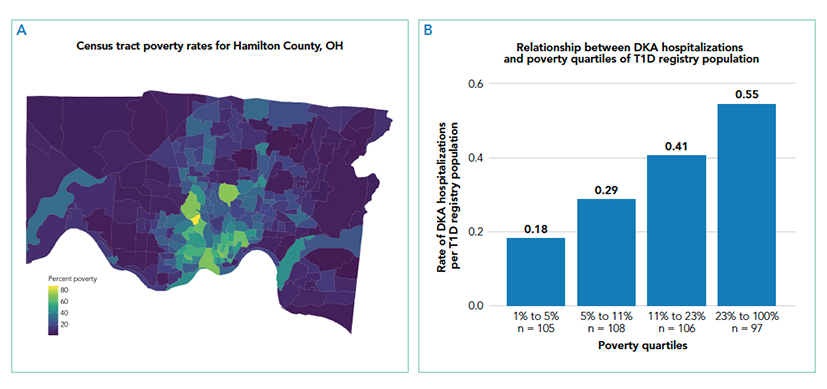

Researchers began with electronic medical record data for 439 T1D patients 18 years old and under at Cincinnati Children’s. The team studied outcomes such as admission for DKA, severity of presentation, and length of stay with exposures including the youth’s home census tract, parent-reported race, and insurance status.

Individually, living in high poverty areas, identifying as Black, and having public insurance were each associated with a higher likelihood of hospitalization for DKA. However, when researchers examined these exposures together in a multivariable model, they found that race was no longer significant. Every 10 percent increase in the census tract poverty rate increased the odds of DKA hospitalization by 22 percent, while public insurance was associated with 2.71-times higher odds of DKA hospitalization in the multivariable model.

“The increased likelihood of hospitalization initially seen for Black patients is likely to be primarily explained by differences in factors related to living in high poverty areas and factors linked to being on public insurance,” says Maxwell. “This shows the importance of addressing the complex interplay on health outcomes between the neighborhood context, healthcare systems, and racism. Interventions that address neighborhood poverty and/or mitigate family-level risks associated with that poverty could have a large effect on reducing preventable DKA hospitalizations.”

To understand and respond to these equity gaps, researchers in endocrinology at Cincinnati Children’s are working with patients, community members, case workers, social workers, and diabetes educators. Led by Nana-Hawa Yayah Jones, MD, the Endocrine team partners with other clinical groups to develop system-wide interventions that address equity gaps across conditions.

About this study

This research was supported by the Cincinnati Children’s Research Foundation’s Diversity and Health Disparity Research Award (31-45310-586000-32-143064).

Read more about a related finding:

Systemic Racism Explains Most Differences in Asthma Re-Admission Rates

View coverage on WVXU:

| Original title: | Socioeconomic and Racial Disparities in Diabetic Ketoacidosis Admissions in Youth With Type 1 Diabetes |

| Published in: | Journal of Hospital Medicine |

| Publish date: | Aug. 18, 2021 |

Research By