Narcolepsy’s Secret Trigger?

Research By: Narong Simakajornboon, MD

Post Date: June 26, 2019 | Publish Date: March 2013

The neurotransmitter hypocretin holds clues to solving this sleep disorder

Daytime wakefulness blinks into dream sleep lasting for several seconds or minutes, and sometimes much longer. It works in reverse as well, with frequent night-sleep interruptions.In children with narcolepsy, the body’s light switch regulating sleep has faulty wiring somewhere behind the wall.

Narcolepsy is unrelenting. But so is Narong Simakajornboon, MD, a sleep specialist and Director of the Sleep Center at Cincinnati Children’s. He is a leading researcher in the field of narcolepsy who also heads the pediatric working group of the Sleep Research Network.

“There appears to be several factors, but there is an autoimmune component that affects the development of narcolepsy,” he says. “The goal is to better understand those potential triggers.”

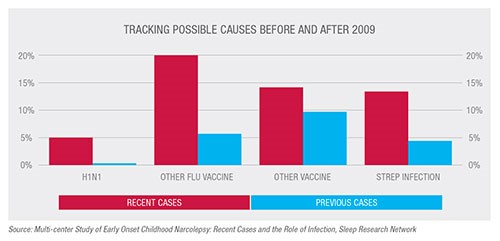

Worldwide, narcolepsy affects about 30 per 100,000 people. Five years ago, rapid increases in childhood narcolepsy in Europe were linked to a single manufacturer of a vaccine for the H1N1 influenza virus. The vaccine connection was surprising, but it could not explain a corresponding rise in Northern China, where the virus itself was a suspected environmental trigger. Nor could the vaccine link explain narcolepsy cases rising in the U.S., where H1N1 vaccination rates were low and the European vaccine was never made available.

Something more complicated is going on, Simakajornboon contends.

In a case report published March 15, 2013, in the Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine, a team of researchers led by Simakajornboon reported a case following streptococcus infection.

Researchers at Stanford theorized that the body’s response to streptococcal infection could trigger narcolepsy in children who have a genetic predisposition to the disorder. The Stanford team noted that the risk of narcolepsy was 5.4 times higher in patients with a physician-diagnosed strep infection.

Also, prior to onset of narcolepsy, there was a higher rate of strep infection in children who had yet to go through puberty than those who had.

“There is an increase in cases that are pre-puberty,” Simakajornboon says. “From five to 10 percent to about 30 percent, and these cases have a pretty rapid onset.”

The body’s autoimmune response to infection might play a key role in what ultimately could be a simple case of mistaken identity.

Studies have shown a strong genetic association between narcolepsy-cataplexy (an abrupt loss of muscle control) and processes in the brain involving leukocyte antigen (HLA) and a T-cell receptor that responds to antigens.

Simakajornboon says there could be “cross-reactivity” between those antibodies and the neurotransmitter hypocretin, which controls alertness. Hypocretin is secreted by the approximately 70,000 neurons in the hypothalamus. Children with narcolepsy have significantly decreased levels of hypocretin.

Simakajornboon and other investigators speculate that the Group A Strep and viral antigen may have or share some epitopes that are similar to the antigen in hypocretin neurons. Epitopes are the parts of an antigen that allow an antibody to attach.

“Therefore,” he says, “after strep or viral infection, the antibody to strep may mistakenly recognize the antigen of hypocretin neurons and attack the neurons.”

Those same neurons also regulate appetite and feeding behavior, which could explain why narcolepsy patients have higher-than-average rates of obesity and weight fluctuation.

“I think that this database will be an important first step in multicenter collaborations for clinical trials in pediatric narcolepsy.”

—Narong Simakajornboon, MD

Simakajornboon and many other researchers believe that both genetic and environmental factors are at work. Some cases are clearly inherited, but others are not.

In the U.S., however, longitudinal data on narcolepsy are limited. Because it is both rare and non-communicable, narcolepsy does not require reporting to the national Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the National Center for Health Statistics.

Simakajornboon is helping to change that through the Sleep Research Network, which has grown to 22 institutions from 14 since he took a leadership role in its pediatric working group in 2010. Before his involvement, the network had no database on pediatric narcolepsy. Now the group has data on 357 cases, with a goal of reaching 700.

“I think that this database will be an important first step in multicenter collaborations for clinical trials in pediatric narcolepsy,” Simakajornboon says. “Also, identifying early cases may lead to more effective early intervention such as immunotherapy.”

Simakajornboon spoke on behalf of the network in June in Seattle at SLEEP 2015, the annual meeting of the Associated Professional Sleep Societies. He noted that symptoms in cases since 2009 differ from previous cases. More recent cases share higher rates of cataplexy and higher likelihood of anxiety, excessive weight gain, abnormal movement and behavior change.

Unlocking the causes of those changing trends could be critical to solving the mystery of the sharp rise in childhood narcolepsy diagnosis. In addition to excessive daytime sleepiness, other symptoms could include sleep paralysis and hypnagogic hallucinations that are unusually vivid and at times very frightening to children.

For now, narcolepsy is treated with medications that minimize excessive daytime sleepiness and other symptoms. Behavioral changes such as avoiding caffeine and adhering to a set schedule for sleep and napping also help.

Finding better treatments is important because sleep is as important to the human body as food and air, Simakajornboon says. “We always see sleep as a normal physiological thing that happens, but people tend to underestimate how sleep impacts your overall life.

Learn more about sleep disorder research at Cincinnati Children’s.

—By Tom O’Neill

(This article originally appeared in the Fall 2015 issue of Research Horizons. Go to the PDF archive to download the magazine.)

| Original title: | Narcolepsy-Cataplexy: Is Streptococcal Infection a Trigger? |

| Published in: | Journal of Clinical Sleep Medicine |

| Publish date: | March 2013 |