Long-Term Study Documents Link Between Adult Crime and Brain Damage from Childhood Lead Exposure

Post Date: October 25, 2021 | Publish Date:

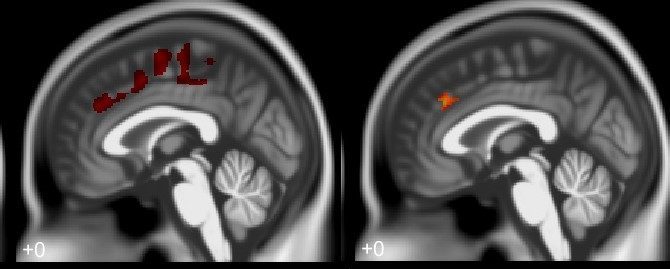

Imaging data links brain matter changes from childhood lead exposure to antisocial behaviors, delinquency, and criminality in adulthood

The October issue of the journal Environmental Research features a powerful study from experts at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati that makes the strongest conclusions to date about a long-suspected connection between toxic lead exposure during childhood and criminal arrests years later as adults.

The study is based on data from the long-running Cincinnati Lead Study cohort and advanced imaging techniques that provide unprecedented detail about adult brain structures that had been injured years before by exposure to lead paint dust and contaminated soils. The report states:

Our results revealed reduced regional gray matter volumes associated with measures of criminal arrests, and that some of these regions corresponded with frontal lobe volume loss associated with childhood blood lead concentrations. Childhood lead exposure harmed the developing brain, especially the regions that are responsible for cognition, decision making, impulse control, socially driven behaviors, emotional regulation, and risky behaviors. Though these results do not establish causality, they provided evidence suggesting that changes in the brain from lead absorption influences the structure of regions recognized for regulating cognition and social behaviors. Structural volume loss in these regions likely imparted functional deficits within these cognitive and behavioral circuits. Without these key regions and cortical networks functioning appropriately, the behavioral consequences could lead to criminal behaviors when individual and societal factors exert their influences on an individual.

Overall, about 78% of the children in the study who by today’s standard had elevated blood-lead levels were later arrested for alleged crimes. On average, each participant was arrested six times.

The toxicity of lead is no secret. Poisonous effects have been documented as far back as 2000 BC. In the 1970s, blood tests revealed widespread evidence of high blood-lead levels, which resulted in a federal ban against leaded gasoline. In recent years, scientists, legal experts and policymakers have debated the extent of the role the leaded gasoline ban played in a long decline in crime rates that began in the 1990s.

In this interview, corresponding author Kim Cecil, PhD, an imaging expert at Cincinnati Children’s Imaging Research Center, discusses the implications of the new findings.

What does this study add to the existing body of knowledge about lead pollution?

Our prior studies (Cecil, 2008; Brubaker, 2010) showed that adult brain volume loss was linked with historic childhood blood lead concentrations in key regions responsible for cognition, decision making abilities, and emotional regulation including impulse and self-control. Both of these studies featured members of the Cincinnati Lead Study cohort.

This work suggested the volume loss could be partially responsible for harmful behaviors previously connected with childhood lead exposure including antisocial behaviors, delinquency, and criminality.

However, we had not directly put together childhood blood lead histories, adult brain volume and criminal arrests into a combined model for analysis. This new study directly accomplishes that aim.

We both replicated and extended our prior studies by illustrating that both gray and white matter volume loss was associated with higher blood lead concentrations at 78 months. The key to this new study was our conjunction analysis, which established statistically significant relationships between the three factors we explored. Our imaging results of brain injury tracked with increasing lead concentrations. Our imaging data also tracked with arrest data.

When combined, the relationship emerged showing smaller volumes in frontal gray matter regions, including the anterior cingulate and supplemental motor areas with higher blood lead concentrations and adult arrest records.

How was the study accomplished?

The Cincinnati Lead Study (CLS) is a longitudinal investigation of children born between 1979 and 1984 to women who lived in the inner-city neighborhoods of Cincinnati, Ohio. These neighborhoods historically had higher levels of children with diagnosed lead poisoning.

The source of lead exposure for these children were their older homes with lead paint residues. Also, lead dust contributed to blood lead concentrations as their homes were located near major interstates where leaded gasoline emissions were deposited for decades before the leaded gasoline ban went into effect in the 1980’s.

The Cincinnati Lead Study created a unique biological repository with childhood blood lead assessments completed twice prenatally, every 3 months from birth until age 5 years and every 6 months until 7 ½ years for the participants.

For each participant, we combined

- Blood lead concentration at 78 months

- Total number of arrests from ages 18-33, specifically the period from 1998 to 2013

- High resolution anatomical imaging of CLS participants when they were between the ages 27-33

We chose the 78-month blood lead concentration as it has been shown to reflect body lead accumulation and relate well to neuropsychological and behavioral assessments. We selected arrests as convictions are subject to plea-bargains, diversion programs and other extra-legal variables.

We also recognized that other things influence brain volumes and criminal arrests, which prompted us to examine factors such as sex, race, gestational age at birth, maternal substance usage, participant substance usage, and childhood socioeconomic status. The CLS cohort is over 90% African-American, with 73% in the lowest socioeconomic levels. The average IQ scores of their mothers was 75 and just over 50% of their mothers had graduated high school at time of delivery.

Nearly all members of the cohort shared many of the factors, which effectively cancels them out, so we can more clearly see the impact of lead. The potential differentiating factors we included were age at time of imaging, age in 2013, birth weight, total intracranial volume, and sex.

Worldwide, experts estimate that approximately 800 million children have blood lead concentrations that exceed the CDC action threshold of 5 micrograms per deciliter. Thus 1 in 3 children globally are adversely impacted by lead exposure.

What most surprised you about these findings?

I am not surprised by the findings. Researchers around the world have been building the case for decades that lead exposure harms the brain, especially the frontal lobe. The imaging studies are simply illustrating it with pictures. With that injury, the consequences in behavior are not unexpected. For the Cincinnati Lead Study, the average blood-lead concentration across the 23 blood lead assessments for the entire cohort was about 13 micrograms per deciliter, with a range among individuals from 4 to 37 micrograms per deciliter. That’s nearly three times higher than the current US Centers for Disease Control (CDC) action level of 5 micrograms per deciliter for blood lead concentration. (Visit CDC.gov for more detail about action levels)

Fortunately, as time has passed, fewer US children have blood lead concentrations as high as we found in the Cincinnati Lead Study. It appears that at least some of the US public health interventions to reduce lead exposure, such as removal of lead from paint and gasoline, have been successful.

However, these measures took too long to implement and do not address the existing lead sources present in older residences, particularly in low income and minority communities. There remains a significant amount of deteriorating housing stock with leaded paint that poses a threat to children. Additional measures to either encapsulate or remove lead in homes and schools have not been fully implemented in many disadvantaged communities.

For example, the recent spike in elevated blood-levels among children in Flint, Michigan, is a reminder that many cities still have not replaced lead in pipes, fixtures and solder connections.

What should be the next steps for tackling lead-exposure risks?

In Western societies, many assume the problem of lead poisoning is a thing of the past. However, recent headlines reveal this is not the case. Today, there remain many sources of lead exposure for children and adults.

In the United States, the primary sources arise from unsafe housing environments, including lead from dust from deteriorating paint in homes built before 1978 or lead in water from compromised water service lines constructed with lead pipes, fixtures and solder.

The US approach involves individual testing of children. However, this does not address the real problem of lead contaminated housing stock, whether that is dust from paint or water from the pipes. While progress is being made slowly, the extent of lead contamination throughout our man-made environment is so extensive it will likely take generations to eradicate as it took generations to produce it. While lead contamination remains in select housing stock, the risks remain for harming children living in those residences.

The CDC advises families to have routine assessments of nutritional and developmental milestones for their children with a pediatrician. Most children get lead exposure from their homes, so it is important to identify lead hazards.

If you live in a house built before 1978, you are likely to have leaded paint. As old paint cracks and peels, it creates lead dust. It is important to clean around windows, play areas, and floors. Also, it is important to wash children’s hands and toys with soap and water, especially before eating and sleeping, to minimize ingestion of leaded dust. Finally, eating healthy foods with calcium, iron, and vitamin C help the body as lead takes the place of essential elements in the cells to cause harm.

In developing regions around the world, there are now more automobiles with lead acid batteries among the population. Improper discarding and informal recycling of lead acid batteries has now resulted in more children exposed to levels of lead exceeding 5 micrograms per deciliter.

Estimates in 2020 report approximately 800 million children exceed this threshold, thus 1 in 3 children globally are adversely impacted by lead exposure. Lead exposure is also significant around the world in lead contaminated soils where food is grown, pottery used in food service, and from cultural practices.

Once a child is injured by lead exposure, what kinds of help can be provided to reduce the risk of criminal behavior as an adult?

Blood lead testing is needed to know if a child is being exposed to lead. The identification and removal of lead sources from the child is essential. For elevated blood lead concentrations, neurodevelopmental assessments can identify cognitive and behavioral deficits. While not specific for lead, academic and behavioral interventions in children can help lessen the impact from lead exposure.

Upon recognizing elevated blood lead concentrations, identifying the neurological deficits are important. Does the child have problem with attention? Does the child exhibit poor self-control? Is the child aggressive? Working with pediatricians, school counselors and other specialists can help target the problem behaviors.

We know the frontal lobe, especially the anterior cingulate, is the portion of the brain involved in making decisions, assessing risks, and anticipating consequences. It also helps regulate impulsivity and emotions. Impairments in these abilities produces adverse consequences.

We also know the families in the study faced multiple disadvantages, as the average CLS participant had experienced an average of six arrests in the period from 1998 up to 2013. It is not clear how these all combine to result in a person committing crimes.

However, our study indicates that lead-induced brain injury is one more thing that can contribute to someone going in that direction. Supportive family and learning environments to enhance educational and occupational opportunities can help reduce the risk of individuals engaging in criminal behavior.

While the Cincinnati Lead Study reports have shown the linkage of high childhood blood lead concentrations and criminal arrests along with smaller frontal lobe volumes, it is important to recognize that not all participants in the Cincinnati Lead Study commit criminal activity. In a new companion study, in Neurotoxicology and Teratology, my colleagues and I found that 22% of CLS participants had never been arrested.

What are your team’s next steps for this research?

The work with the CLS participants is harder now because they are busy and have moved on in their lives. We are now interested in the very low lead concentration (<1 micrograms per deciliter) effects, which is more relevant for contemporary US children. We also are focusing on mixtures of known and potential environmental neurotoxicants (flame retardants, air pollutants, pesticides, etc.).

From ongoing research exploring other conditions, such as ADHD, and man-made environmental chemicals, we find that even lead levels below the cause-for-action value of 5 micrograms per deciliter still impact our studies. Our analyses require us to put blood lead concentrations into our models.

We plan to continue our neuroimaging analyses of structural and functional network connectivity to hopefully tease apart the contributions from low level lead and other man-made environmental chemicals.