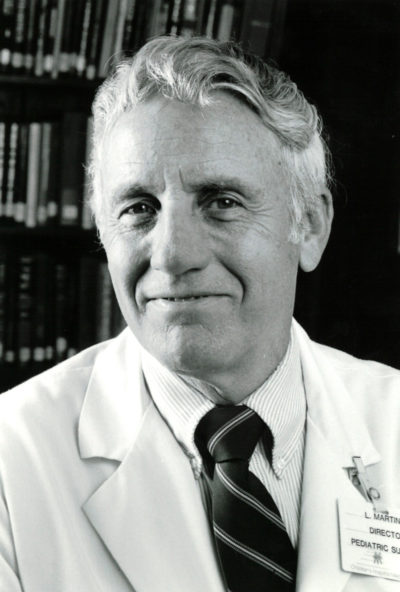

In Memoriam: Lester Martin, MD 1923-2020

Post Date: April 22, 2020 | Publish Date:

If we had a pantheon of heroes at Cincinnati Children’s, Lester Martin would surely be prominently inscribed, along with William Cooper Procter; A. Graeme Mitchell; Albert Sabin; Josef Warkany; Sam Kaplan; Fred Silverman; Bill Schubert, Katie Dodd and the like.

Lester Warren Martin, MD, passed away on March 13, after a battle with congestive heart failure. He was 96 years old.

Martin, a graduate of Harvard Medical School, trained at Boston Children’s Hospital under Robert Gross, MD, an outstanding surgeon, clinician and teacher who inspired him to become a surgeon. It seemed a lofty ambition for an Edwards, Missouri, farm boy who grew up during the Great Depression. In fact, he studied for two years to be a veterinarian, thinking medical school was beyond his means. But his education was interrupted by WWII. He served in the Army for three years, after which he used his GI benefits to pay for medical school. “It was a dream come true,” he said.

In those days, there was no formal pediatric surgical training or certification. General surgeons performed pediatric surgery mostly for free, believing no one could make a living at it. When Martin first arrived at Cincinnati Children’s in 1957, he was the first full-time pediatric surgeon on staff. He went on to establish one of the premiere pediatric surgical programs in the world, graduating at least 25 surgical fellows who have had a global impact.

Martin achieved a great deal in his 32 years here. He developed an innovative procedure for children with ulcerative colitis that eliminated the need for an ostomy bag. The procedure, called the Lester Martin Pull-Through Method, remains the world standard today. In addition, he performed the first liver and kidney transplants in Ohio.

He also drew on his early veterinarian training to help treat animals at the Cincinnati Zoo, e.g., repairing an umbilical hernia in a baboon and a cleft palate in a white tiger cub.

When asked about the most satisfying aspects of his career, Martin ranked training pediatric surgeons first, followed by having a part in building a children’s hospital and a department of surgery in which teaching, research and administration were all directed to improving the quality of care for children locally and internationally. Finally, he loved doing surgery itself, knowing that, in many cases, it was going to make a profound difference in the lives of his patients and their families.

Martin received numerous honors for his work, including the Drake Medal from the University of Cincinnati College of Medicine; the Ladd Medal from the Surgical Section of the American Academy of Pediatrics, and the Founder’s Award from the Cincinnati Pediatric Society.

He was preceded in death by his wife of over 65 years, Joan Belanger Martin, and his daughter, Sally Martin Stewart. He is survived by his daughters, Betsy Smith, Susan Weinert, Janet Bertolino and his son David Martin, 13 grandchildren and three great-grandchildren.

Lester Martin’s Colleagues Remember …

We were so very challenged by the complex neonatal surgical cases which we were just learning to manage in the early days of intensive care for newborns. Our concerns about caring for the infant—especially those of the family—were transformed into confidence and hope when Lester Martin came to the bedside and began to lead the team. His skills as a surgeon, physician, teacher and kind caregiver are remembered by all of us lucky enough to work alongside him and by the countless children and families he served for so many years at Cincinnati Children’s.

— Jeffrey Whitsett, MD

Lester Martin was a gentle man, a scholar and a superb surgeon. I liked and respected him since he first interviewed me for my radiology job back in 1979. Rest in peace.

— Alan Oestreich, MD

He was one of my teachers, and according to Bill Schubert, the best pediatrician in Cincinnati. And I thought Bill was.

As first-year residents, we had a brutal month of pediatric surgery (January 1977)—rounds at 0530, etc. But one day he said, “Manny, you want to do a splenectomy?” I had to say yes, but I was scared to death. As it turned out, his guiding and magical hands got the patient through it, and then he congratulated me! I have no idea today how that happened.

He was a true artist, genius and a great gentleman.

He had chronic congestive heart failure. At age 92, Lester asked his cardiologist if he would put him on the transplant list.

What a man.

— Manny Doyne, MD

So sad to hear this news. He was a legend when we were residents, and his productivity was astonishing.

— Jeff Loughead, MD

When I was a resident back in the 1960s, Dr. Martin consulted on a very sick infant. We reviewed the portable chest X-ray, after which he suggested we take it upstairs to review with Dr. Fred Silverman. (Remember, no ultrasound or CT back then.) Dr. Silverman viewed the film and said he thought it was a pleural effusion, saying that if you put the needle right here—pointing to the exact spot on the X-ray—you would get 15 ml of fluid. We returned to 1 East where Dr. Martin performed a needle aspiration. As the infant’s breathing improved, Lester smiled and said to me with a laugh, “Tell Dr. Silverman we only got 14 ml from the chest.” Later in the day I repeated this to Dr. Silverman who gave a wry grin and replied, “Tell Dr. Martin he didn’t put the needle in the right spot.”

— K. Kurt Bofinger, MD

Lester Martin was one of the truly influential clinicians at Cincinnati Children’s during the 1960s-90s. He, Clark West, Bill Schubert, Sam Kaplan, Jim McAdams and Bea Lampkin were the basis for the outstanding clinical environment that exists at the medical center today. Dr. Martin was a clinician’s clinician with an outstanding fund of knowledge and tremendous skills in application. He was a cutting-edge surgeon, a true innovator. He was a gentle, understanding physician whose style was valued by patients. He was an exceptional teacher and provided excellent hands-on teaching to medical students, residents, fellows and young faculty.

— Jim Heubi, MD

Lester Martin was quiet, very self-confident, dedicated—he exuded calmness. He routinely worked 18-hour days.

He did everything surgical—that included suturing all lacerations in the Emergency Department. He either did it or had his fellow do it—a form of moonlighting for him. Unfortunately, it often meant families had to wait until a surgeon was free. I came in 1974, fresh out of three years of general practice in the Navy. I had seen thousands of patients and repaired hundreds of lacerations.

My neighbor’s child fell and cut his scalp. They came to the ED—it was a simple three-suture wound in the scalp (we were not using staples at that time). They had to wait several hours for a surgeon. Finally, I sutured it. The next day, Bill Schubert called me to his office and simply said, “That is not the way we do things in Cincinnati.” That process did not really change until Rich Ruddy came as director of Emergency Medicine.

Another time, I was moonlighting in the ED one night. We did not have attendings there regularly. A teenage boy was brought in, a victim of domestic violence. He had been thrown through a glass door by his father. He was bleeding profusely from multiple scalp lacerations. The bleeding was extensive, and I was worried. We could not get it under control. Lester was walking through, saw us struggling, asked for a mosquito clamp and stopped the gushing in seconds.

When I finished my fellowship, I was interested in gastroesophageal reflux in infants—there was a theory that it was a cause of sudden infant death. Many infants around the country were having invasive fundoplications done based on minimal symptoms. (Ed. Note: Fundoplication is a last-resort surgery to correct gastroesophageal reflux disorder [GERD] or a hiatal hernia.) Lester thought that was wrong. He supported my efforts to begin studying the issue, and we published one of the first papers on the topics. Due to Lester’s interest, Cincinnati never jumped on the fundoplication bandwagon.

— Mike Farrell, MD