How to Save Babies? Find Every Mother

Post Date: July 1, 2019 | Publish Date: Winter 2018

If the first step to solving a problem is admitting it exists, officials in Hamilton County, Ohio—where Cincinnati Children’s calls home—know they have one whopper of a wicked problem.

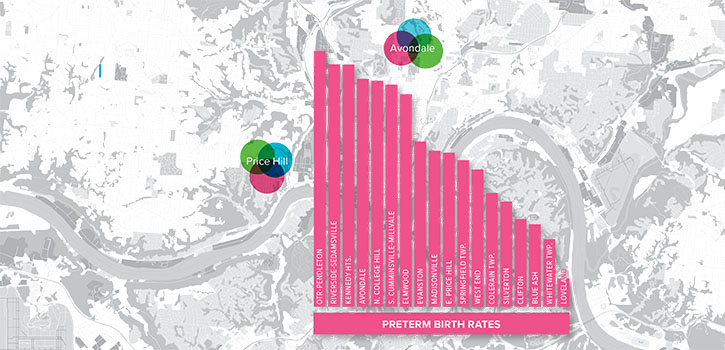

Infant mortality and preterm birth rates here are among the nation’s worst. Some neighborhoods, especially in Cincinnati’s inner city, have rates rivaling third-world countries. From the years 2007 to 2011, Hamilton County’s infant mortality was 10.8 per 1,000 live births. That ranks among the worst 10 percent of all counties nationwide.

Hidden within that overall statistic, an estimated 40 percent of premature infants born at 25 weeks gestation or earlier die within their first day.

“Many of these babies don’t even get out of the delivery room. The most modern and sophisticated interventions on the planet can’t help them,” says James Greenberg, MD, Co-Director of the Perinatal Institute, and a devoted disciple to saving as many babies as possible through collaborative human endeavor.

A ‘WICKED’ PROBLEM

“There is literature around something that is actually called a ‘wicked problem,’” Greenberg says. “Infant mortality is a wicked problem. It means the problems are complex, they have a lot of variables, some variables confound others, and they are hard to solve.”

In Hamilton County, debate continues over the possible reasons behind the high infant mortality rate and its related instigator, extreme preterm birth (defined as births at less than 28 weeks gestation). Solid answers remain elusive.

For example, statistics clearly show that mortality rates run much higher for black babies. Experts still debate the cause, which is not adequately explained by biomedical factors or economic disadvantage.

Experts also differ over how specific behaviors may influence infant mortality, such as smoking during pregnancy, following safe sleep practices for infants, spacing between pregnancies, and access to prenatal care. Only recently have suspected gene loci emerged from a large study of expectant mothers that may explain how the length of pregnancy and onset of labor are controlled.

Meanwhile, ongoing research pokes holes in other suspected causes.

Take pregnant teenagers, who have a higher risk of giving birth to a preterm baby. Teenage pregnancy once was thought to be an important driver of infant mortality, but Greenberg notes that teenage pregnancy rates have dropped in the last decade while infant mortality rates remain stubbornly high.

Another example is opioid addiction, which had been suspected as a contributing factor in infant mortality. Subsequent research shows maternal addiction does not on its own significantly impact infant mortality, although other health behaviors associated with opioid addiction (like smoking cigarettes) have strong links to infant mortality.

Both examples underscore the shifting layers of complexity that come with tackling wicked problems like infant mortality and premature birth.

CRADLE CINCINNATI TAKES ON PRETERM BIRTH CHALLENGE

When Greenberg and Cincinnati Children’s colleagues started the Perinatal Institute in 2009, a chief new objective was confronting infant mortality. This included Perinatal Institute co-founder and Co-Director Jeffrey Whitsett, MD, a pioneer in neonatal pulmonary research and care.

Data from previous years had made Hamilton County’s high infant mortality rates appallingly clear. The problem even plagued Cincinnati Children’s home turf, the socioeconomically challenged, mostly black neighborhood of Avondale.

Considered an anchor institution in the city and a global leader in child health, “the unique position of Cincinnati Children’s comes with responsibilities,” Greenberg says. Still, the hugeness of the challenge was obvious, as was the abundant realization that help was needed.

A new level of community involvement arrived in 2012 through a collaboration called Cradle Cincinnati. The organization was co-founded by Greenberg and Elizabeth Kelly, MD, Director of the Community Women’s Health Division at the University of Cincinnati’s Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology.

The collaboration is based at Cincinnati Children’s but has grown to include all the city’s hospital birthing centers, the Cincinnati Health Department, and other city and county officials. Several community health agencies including Every Child Succeeds and Healthy Moms and Babes participate as well.

Just a few years into the effort, Cradle Cincinnati began delivering results. During the years 2012 to 2016, Hamilton County’s infant mortality rate dropped to 8.96 per 1,000 births, down from 10.8 in 2007-2011. That lower figure remains one of the highest rates in Ohio and nationally, but represents clear progress.

Even so, the work remains far from complete, says Ryan Adcock, Cradle Cincinnati’s Executive Director, and an example in his own right of going against convention to find a path to success.

Adcock was not trained as a public health professional. He is a former chief of staff for a Cincinnati mayor, and previously worked as a songwriter. Yet he plays a vital role in Cradle Cincinnati’s success as a knowledgeable and enthusiastic convener of stakeholders, a catalyst, and a cheerleader for the community-wide effort.

“The message is, there is hope,” Adcock says. “People sometimes come to this issue with hopelessness or thinking it’s just too big. It is really hard and it takes a lot of intentionality. But we’ve shown when the right folks come together in the right way, it can make a difference.”

START STRONG SLASHES PRETERM BIRTHS IN AVONDALE

If the collective “who” of Cradle Cincinnati provides the strength, the “how” is the secret sauce to the collaborative’s success so far.

Defanging the wickedness of the infant mortality problem requires changing the rules of engagement, leaders say. That involves adherence to gathering good data, listening to the people most affected by the problem, and acting on the insights to get better at what we do every day, according to Robert Kahn, MD, MPH, a co-founder of the Start Strong initiative.

It was formed to apply these strategies to the problem of infant mortality. Launched in 2013 with $5.2 million from donors, including $3.2 million from the Bethesda Foundation, Start Strong serves as a learning network that informs the larger Cradle Cincinnati effort.

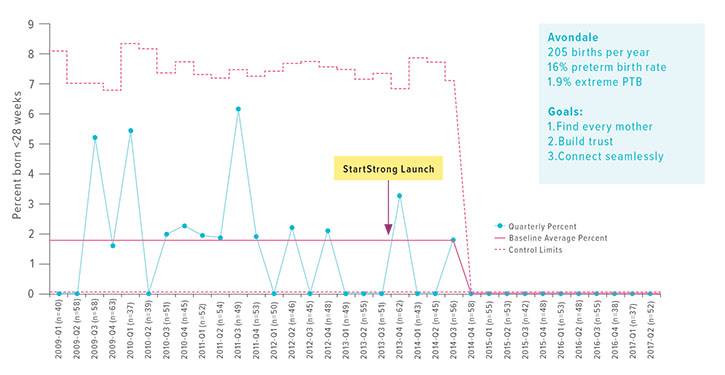

The new initiative’s primary goal: decrease the high number of extreme preterm births occurring in Avondale.

When the initiative started, Avondale’s infant mortality rate was 22.1 per 1,000 births—far higher than the U.S. average of 5 per 1,000. By 2016, the rate had plummeted to about three infant deaths per 1,000—including zero extremely premature births.

“Something special is happening in Avondale,” Kahn says.

Kahn is Associate Chair for Community Health at Cincinnati Children’s. He has a long track record of community health leadership including efforts to tackle substandard housing, childhood asthma, and other entrenched inner-city health challenges.

He credits the Start Strong success to an effort that placed emphasis on redesigning prenatal care to focus on mothers and their needs. This includes providing in-home support to every expectant mother in the neighborhood, and building trust by solving critical problems for women living in poverty.

The work started with an ethnography, a deep-dive listening exercise to understand the challenges facing expectant neighborhood moms. This increased insight and empathy between mothers and care providers, Kahn says. The Start Strong team held community dinners to meet people, hear their insights, share ideas, and get a sense of what does and does not work.

Caregivers learned many of the moms faced significant economic, social and environmental challenges to having a healthy pregnancy, Kahn says. Such challenges can produce toxic levels of stress, which experts theorize could be harming their yet-to-be-born babies.

Data from the listening exercise fed ideas that led to new approaches to supporting mothers. These were used to link and activate all the community providers serving women from Avondale.

Community providers working with the neighborhood then learned from each other and customized their own approaches to meet the needs of expecting moms. According to Kahn, this created an engaged community outreach network of people who could talk, share information and help identify the women.

One goal of the program was to help participating obstetric clinics, home health visitors and community agencies to work together to reduce some of the barriers a mom might face in providing a healthy environment for her baby. These include streamlining access to prenatal care, enhancing referrals to community providers, or offering legal advocacy to address unstable housing or domestic violence.

“We centered the work around what moms need and want as opposed to technically perfect medical care,” Kahn says. “It’s about them, not our busy clinical schedule.”

But the first and primary barrier was finding every pregnant woman living in Avondale. Pregnant moms cannot be helped if no one knows who they are, Kahn says. It was finding moms that made other interventions possible.

REDESIGN IN ACTION

One example of how these new approaches impacted the basic mechanics of health care delivery occurred at two clinics serving Avondale moms, one run by UC and another by Good Samaritan Hospital. The clinics transformed their clinical model of engagement, says Dawn Denno, Cincinnati Children’s Senior Director of Community and Population Health.

Depending on the clinic, a doctor or a nurse case manager was assigned to each expectant mom to serve as her central point of contact and problem solver. Previously, a mom might see any number of different staff members during prenatal visits.

The new model called for building trust through forming more reliable relationships. Staff members have responded with enthusiasm to the change.

Denno recalls how staff at the Good Samaritan clinic reacted during a meeting when a pregnant mother with severe diabetes arrived after missing several previous appointments.

“One of the people in the room jumped up and said, ‘Ms. So and So just entered the building. I have to go where she is.’ It was like a surveillance system,” Denno says. “Moms come in, and they swarm them.”

WORK CONTINUES TO REDUCE INFANT MORTALITY

In January, Cradle Cincinnati officials announced the rate of fatal birth defects for Hamilton County, a leading cause of infant mortality. The report shows that from 2012 to 2016, when 486 infants died, 88 of those (18.7 percent) died from a fatal birth defect. According to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, one in 33 babies is born with a birth defect, but only a small percentage are fatal.

The announcement came with an urgent message from the community coalition that is Cradle Cincinnati to families in the Hamilton County-Cincinnati area. While not all birth defects can be prevented, families can take the steps to lower their risk of fatal birth defects.

These steps include:

- Controlling diabetes during pregnancy, because poor diabetes control during pregnancy increases the chance for birth defects and other problems,

- Take prenatal vitamins with folic acid, which can help prevent major birth defects of the developing brain and spine,

- Maintain a healthy weight, and

- Get a rubella vaccine, which can protect women against infections that can cause birth defects.

And very importantly, in the interest of finding every mother, officials urged women to see their health care provider as soon as they find out they are pregnant.

—By Nick Miller

(This article originally appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of Research Horizons)