Growth Hormone, Estrogen Exposure Combine to Trigger Early Puberty, Raise Risk of Breast Cancer

Research By: Frank Biro, MD

Post Date: September 1, 2020 | Publish Date: Sept. 1, 2020

Groundbreaking findings based on following 180+ girls for 14 years

When girls reach puberty at an unusually early age, they face a significantly higher risk of developing breast cancer later in life. Now, experts at Cincinnati Children’s and the University of Cincinnati offer a new, unified explanation for why that increased risk occurs.

Detailed findings were published online Sept. 1, 2020, in the Journal of Adolescent Health. The study was led by Frank Biro, MD, one of the nation’s leading experts on puberty and the environment and a team of colleagues.

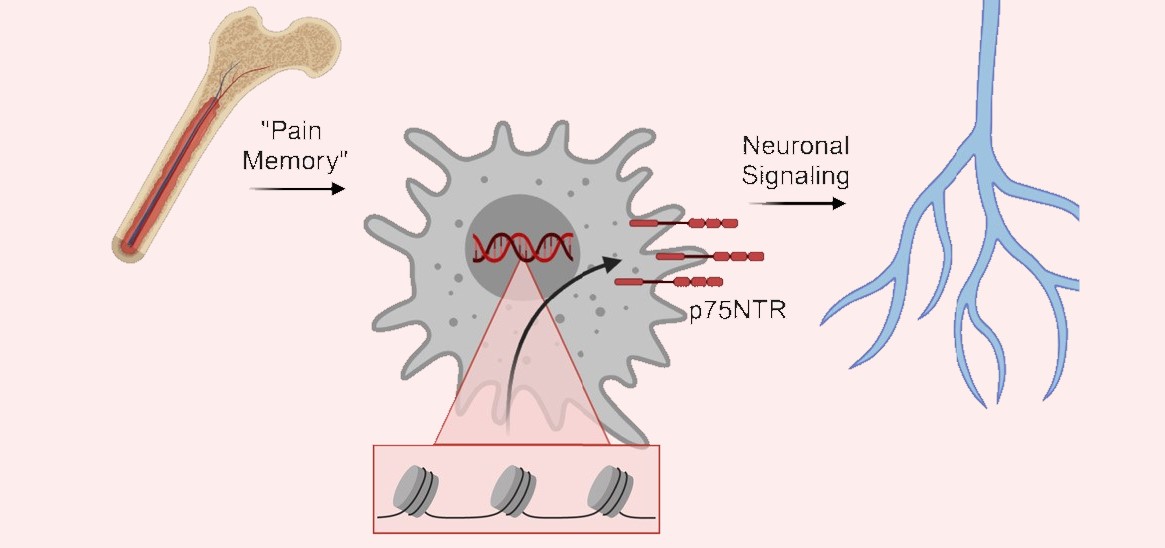

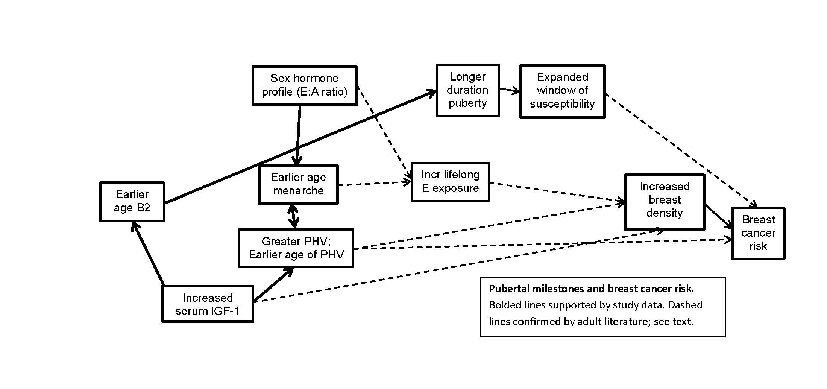

Essentially, girls who enter puberty early in life—as measured by early breast development and age of first menstrual period—have a longer window of susceptibility to breast cancer. This window stays propped open for too long because their bodies have higher concentrations of growth hormone and they experience a slower progression (“tempo”) during puberty. This in turn results in a longer exposure to environmental factors that could influence the developing breast tissue.

“We have been concerned for many years about girls entering puberty at steadily younger ages. A number of studies have established a link between early puberty and breast cancer risk,” Biro says. “Our study is one of the very few to gather many years of data to comprehensively track the changes young women experience.”

Previous studies have linked earlier age of menarche (the first menstrual period), greater pubertal growth velocity, and earlier age of the pubertal growth spurt as being related to breast cancer risk. These three pubertal factors are also related to each other.

Previous studies also have found that breast development has been occurring at younger ages, with some girls showing signs as early as age 7. Typically, menstrual periods begin two to three years afterwards. For most girls, their periods begin around ages 12 or 13, Biro says.

The age of breast development has been dropping much faster than the age of menarche. The new study is part of a long-running project to find out why.

“We found important, dynamic relationships between the concentration of human growth factor and of other hormones at critical stages in growth that were not evident in short-term studies and cross-sectional studies. This gives us a more accurate understanding of why early puberty poses a breast cancer risk—and suggests ways for families to help their daughters reduce that risk.”

When a growth window stays open too long

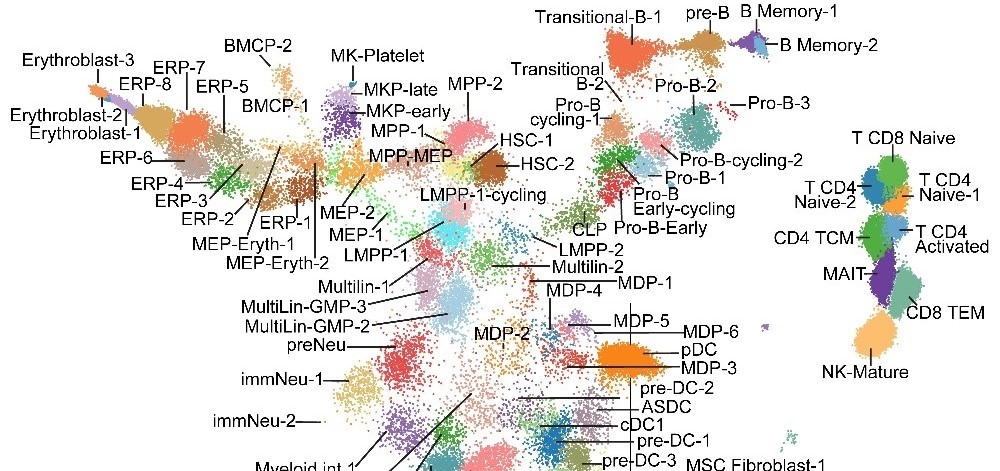

Of several biochemical changes happening as young girls grow, the new study reports that hormonal factors found in adult women that have been associated with elevated breast cancer risk also are associated with early puberty. These include higher concentrations of the growth factor IGF-1, and the ratio between the hormones estrone and androstenedione (E:A). IGF-1 is a potent growth stimulant that is associated with breast density and with breast cancer in adult women. A greater ratio of estrone to androstenedione leads to greater overall exposure to estrogen, another risk factor for breast cancer.

What does this mean for young women who start puberty early?

These findings suggest that girls experiencing early puberty can take steps throughout their lives to reduce their breast cancer risk. These include:

- Healthy exercise and eating habits to avoid obesity, a known risk factor for breast cancer.

- Specifically increasing consumption of fruits, vegetables, soy and other foods that contain plant-based weak estrogens called phytoestrogens. Previous work from the Breast Cancer and the Environment group has found that increased levels of phytoestrogens in the body can replace other stronger estrogens and thus can moderately delay the onset of puberty.

- Another approach includes living a “greener” lifestyle that minimizes exposure to surprisingly common “endocrine disrupting” chemicals, such as phthalates found in many consumer products. See below for more information about phthalates.

- In some of the most extreme cases, which doctors define as “precocious” puberty, the new data may help clinicians decide which girls are most at-risk and should consider treatments to delay the onset of puberty.

- Longer term, targeting IGF-1 may become an alternative or additional approach for slowing down early puberty.

A long, complex project

The work began in 2004 as part of the “Growing Up Female” study conducted by the Breast Cancer and the Environment Research Program in collaboration with two other medical centers in New York City and Northern California. The Cincinnati team worked with parents and schools to follow a group of more than 370 girls who entered the study at ages 6 and 7.

The current study reflects data from more than 180 girls, all from the Cincinnati region, who had stayed with the project all 14 years and provided multiple blood samples.

In the first six years of the study, girls were seen every six months either at their schools or at Cincinnati Children’s. In the following years, families brought their daughters back to Cincinnati Children’s once a year until 2018, when the girls had reached ages 20 and 21. Participants received small payments for their time and were invited to various events over the years to share study results and have fun.

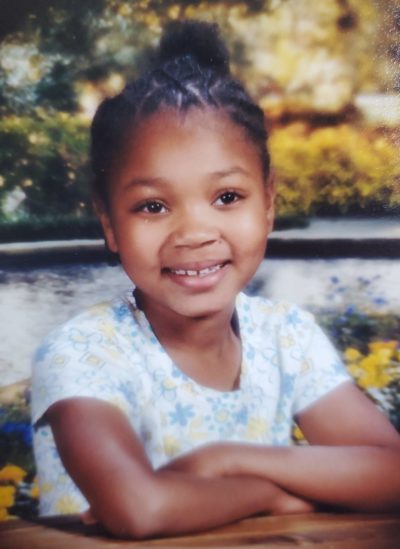

“My mom told me there was a study going on that would help the doctors learn more about how young women’s bodies grow. I thought that would be interesting because I didn’t know much about any of that,” says Heaven Taylor, a Cincinnati-area resident who participated in the study.

The research team tracked numerous measures, including height, weight and “height velocity.” They tracked when breast development began and when menstrual cycles started. They analyzed blood to measure hormone levels and gathered a wide range of demographic, geographic, environmental and behavioral information from questionnaires and interviews.

Among the findings:

- Earlier puberty onset was associated with greater peak height velocity (PHV).

- The duration of the pubertal growth spurt was greatest in the earliest-maturing girls

- Higher concentrations of growth hormone were correlated with earlier age of breast development, longer duration of puberty, and earlier age of peak height velocity.

- Girls starting puberty early also showed greater conversion of hormone precursors to estrogen.

PHOTO GALLERY: Heaven Taylor through the years. Click arrows along sides of photos to see the next image.

Taylor recalls having her first period at school, long before she expected it.

“I remember that like it was yesterday,” Taylor says. “When it happened, I thought I was dying. I freaked out and called my mom from the bathroom. She wasn’t that surprised, though. She said something like, ‘Well, you’re a woman now.’ And I said, ‘I don’t want that!’ Then she said, ‘Well, there’s no going back now.’ ”

Taylor recalls having her first period around age 10, which is unusually early. “Typically, menarche starts at about age 12 for Black girls,” Biro says.

What’s Next?

This study represents one of the last major reports from the Growing Up Female project. There are no current plans, nor funding, to track the participants for the rest of their lives.

More study will be needed to determine if managing IGF-1 has value in preventing early puberty, Biro says. Likewise, other research projects may be needed to address certain limitations of this research.

For example, the Cincinnati study was unable to recruit large numbers of Latina and Asian girls, so some of the findings may not apply to them. The study did not attempt to search for genetic variations that may or may not contribute to early puberty risk. It also does not address ongoing questions, studied primarily in adults, about cancer risks posed by breast density.

To Biro, the important lesson for families is that learning more about the hormone combinations that drive early puberty will help clinicians to discover approaches that help more women reduce their risk of breast cancer.

“Risk is not fate,” Biro says. “There are steps people can take to minimize their risks.”

About this study

Co-authors included Catherine Gordon, MD, MSc, Boston Children’s; Bin Huang, PhD, Cincinnati Children’s; and Susan Pinney, PhD, University of Cincinnati.

Funding for this research included multiple grants from the National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, the federal Public Health Service and the Maternal and Child Health Bureau: U01ES019453, UL1RR026314, T71MC00009, P30ES006096, and R01ES029133.

Read more information about phthalates

Watch a video explaining the Growing Up Female research project

| Original title: | Puberty as a Window of Susceptibility for Breast Cancer Risk: Exploring the Physiologic Mechanisms |

| Published in: | Journal of Adolescent Health |

| Publish date: | Sept. 1, 2020 |

Research By