Families Converge in Cincinnati to Improve Outcomes for Rare Smith-Kingsmore Syndrome

Post Date: November 21, 2019 | Publish Date:

Scientists share learnings and gather data needed to design a future clinical trial

Smith-Kingsmore syndrome (SKS) is so rare that experts know of only 50 to 60 cases worldwide. So when 17 families traveled from as far as Brazil and England to visit Cincinnati Children’s for a two-day scientific and educational gathering in October 2019, it was a truly special event.

Participating families that had felt isolated at home gained an opportunity to share experiences with other families coping with an extremely rare condition. They also had the chance to meet in-person with scientists chasing down the causes and potential treatments for SKS.

In addition to sharing experiences and making connections, the event allowed investigators led by Carlos Prada, MD, to gather the world’s largest natural history study of patients with SKS, which is instrumental as a baseline for future clinical trials. The data is expected to provide families and physicians with a more precise set of symptoms to define SKS, stronger ideas about underlying genetic and molecular factors driving the syndrome, and more effective ways to support children growing up with the condition.

“This is probably the largest gathering of these patients anywhere in the world,” says Louis Muglia, MD, PhD, Director, Division of Human Genetics at Cincinnati Children’s. “This really integrates our expertise in circadian medicine with previously unrecognized complications. It also builds on our considerable experience with tuberous sclerosis complex in a way that we hope can help these families.”

Still learning about SKS

Smith-Kingsmore syndrome is a very new condition. The breakthrough occurred in 2013 after Laurie Smith, MD, PhD, encountered a young girl named Lila while working at Children’s Mercy Hospital in Kansas City. Lila had presented with unexplained megalencephaly and uncontrollable seizures, and caregivers were hoping genetic testing would provide the family with answers.

Smith collaborated with Stephen Kingsmore, MD, Dsc, at Rady Children’s Institute for Genomic Medicine in San Diego to conduct whole-exome sequencing analysis of a biosample from Lila. Instead of detecting any of the known genetic signatures for rare neurological diseases, the team discovered that Lila had a novel germline mutation in the mammalian target of rapamycin (mTOR) gene. Smith and Kingsmore published their findings in 2013 in the Journal of Genomes and Exomes.

Since then, the number of diagnosed patients has grown to approximately 60. Families have formed a Facebook group, a website and, most recently, a fundraising foundation to share information and learn alongside investigators.

SKS appears to be a systemic condition with a constellation of features that vary in intensity. Brain-related symptoms include an enlarged brain (megalencephaly) at birth and rapid head growth in the first 6 months, plus white matter abnormalities, seizures, intellectual, speech and developmental delays.

Many children with SKS have distinct facial features including tall foreheads, down-slanting eyelid openings (palpebral fissures), an open-mouth appearance, short noses with flat nasal bridges, widely spaced eyes (hypertelorism), and prominent long clefts under the nose (philtrum).

Many also experience sleep disorders, repetitive motion behaviors, feeding difficulties and digestive issues.

Cincinnati Children’s Gets Involved

As is common with many rare diseases, families can go years without finding an accurate diagnosis. That was the experience of Kristen and Mike Groseclose, who launched the Smith-Kingsmore Syndrome website, in 2018 shortly after their son Jack was diagnosed with SKS.

“For some people getting a diagnosis can be one of the worst days of their lives,” Kristen says. “But for us it was one of the best, because we went 15 years without knowing anything.”

Jack was born in 2002 in New Jersey with an unusually large head but no other clear symptoms of a serious condition. However, it became obvious to his parents that Jack was not reaching expected milestones. Just after his first birthday, doctors confirmed the family’s fears: Jack had severe, global developmental delays, but they could not explain the cause.

The family worked with a variety of physicians and therapists, eventually finding their way to Cincinnati Children’s where they met Carlos Prada, MD, an expert in clinical genetics and RASopathies, and Darcy Krueger, MD, PhD, an expert in tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC), an uncommon neurological condition that turns out to have a close relationship with SKS.

Gene testing conducted at Cincinnati Children’s confirmed that Jack had the SKS mutation, which also led to a treatment attempt.

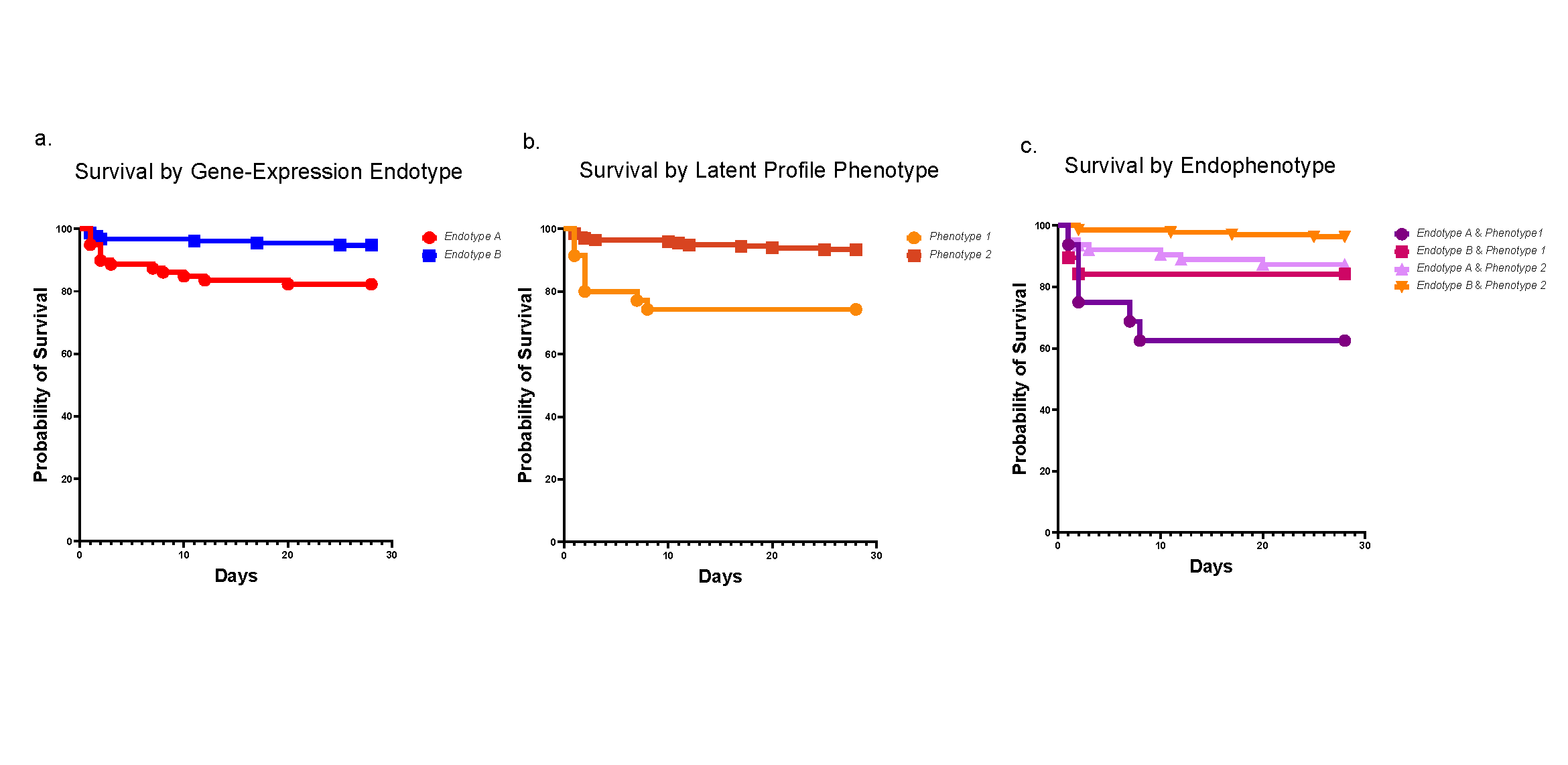

Research over the years, led in large part by Krueger, had revealed that TSC also is driven by dysfunctions in the mTOR pathway. Krueger and colleagues demonstrated that several manifestations of TSC, including brain tumors and seizures, could be controlled through the mTOR inhibitors sirolimus and everolimus.

Suspecting they were facing a new “mTORopathy,” the doctors at Cincinnati Children’s placed Jack on a daily dose of sirolimus.

Enter Circadian Medicine

At first the treatment worked well. Some of Jack’s behavioral issues improved dramatically. However, he also turned into a “night owl,” a disruptive sleep pattern that was causing a new set of issues.

Jack’s new problems happened to occur in the right place.

It turns out that while some scientists were studying how mTOR dysfunction affects brain development, another set of scientists were learning that mTOR also serves as one of the core genes regulating the body’s circadian clock.

At Cincinnati Children’s, John Hogenesch, PhD, and David Smith, MD, PhD, have been leaders in studying how medication effectiveness can be affected by circadian rhythms, and how medications can affect the body’s clockworks. They soon concluded that Jack’s sleeping problems were caused by receiving too much of the sirolimus. This in turn opened a new page for families looking for ways to manage symptoms.

At the gathering in October, experts at Cincinnati Children’s walked families through a series of tips and techniques for measuring and managing sleep disorders. For children with SKS they say sleep may serve as both a potential biomarker for monitoring the condition as well as a form of treatment.

“We do believe that achieving healthy sleep could ameliorate a number of symptoms for children with SKS,” David Smith says.

Looking ahead

In August 2019, the Grosecloses and other families launched the Smith-Kingsmore Foundation to continue raising awareness about the condition and to raise funds for more research.

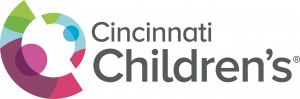

More work is needed to prepare for potential clinical trials of proposed SKS treatments, investigators say. Designing a meaningful clinical trial for a very rare condition that also has a complex web of symptoms will be no easy task, Krueger says.

However, the effort is worth it, for children with SKS and beyond. Krueger says what scientists learn about SKS, combined with knowledge gleaned about TSC, could lead to deeper understanding and better management of other more-common conditions such as seizures and autism spectrum disorders.

Mike Groseclose says the event held at Cincinnati Children’s was just the beginning.

“We want to blaze a trail here. We know that SKS is underdiagnosed, but we don’t know if there are another 1,000 people or 100,000 people,” Groseclose says. “It was awesome to learn more about the progress made so far. Even though it’s in its infancy, the science is much further along than we understood. It was great for everybody to hear that.”