Asthma Improvement Collaborative Reduces Hospital Re-Visits by 41%

Research By: Mona Mansour, MD, MS | Carolyn Kercsmar, MD | Andrew Beck, MD, MPH

Post Date: July 1, 2019 | Publish Date: Nov. 1, 2017

Yes, the needle can be moved.

From a distance, the health disparities exacerbated by poverty can seem like a Gordian knot. Lack of educational opportunities. Lack of transportation. Lack of access to care. Increased dangers from pollution and poor housing conditions. Instability in the home. Racial disparities. Distrust of the health care system.

All of these factors, and more, make it hard for low-income families to fully follow their doctors’ prescriptions for managing a serious chronic disease like asthma. Hospitals and clinics in big cities across America live this reality every day.

But outcomes can be improved. Children with poorly controlled asthma can achieve dramatically improved outcomes, even among families facing desperate situations. That’s what a five-year improvement effort organized by Cincinnati Children’s and a group of committed community organizations demonstrated with results published in November 2017 in JAMA Pediatrics.

The project involved forming a learning network of people working in hospital and outpatient care settings who collaborated with families, pharmacies, school nurses and city health officials. This virtual village recommended and supported changes that have improved day-to-day life for children with asthma while saving health care costs by reducing hospital re-admissions.

“I do think this study is fairly unique in the number of partners we brought together, the scope of the work, and the ability to impact outcomes,” says Mona Mansour, MD, MS, Director of Primary Care at Cincinnati Children’s and a co-author of the study.

“One of the hardest metrics to move in asthma care is high utilization of emergency services,” says Carolyn Kercsmar, MD, Director of the Asthma Center, and another co-author. “But beyond the statistics, what we’re really doing is reducing the disruption that families face when their children get hospitalized or come to the emergency room for asthma exacerbations.”

BREAKING DOWN A BIG PROBLEM

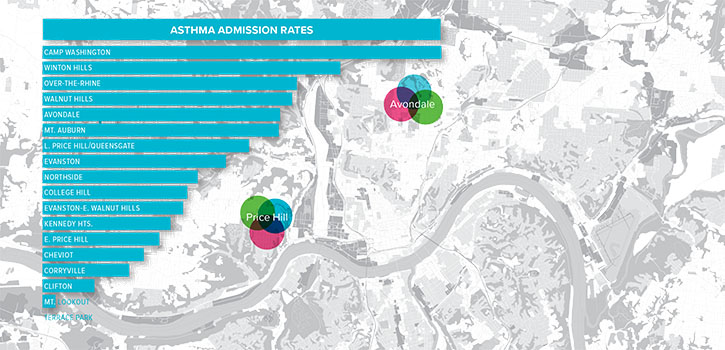

The scale of the asthma challenge here is daunting. In Hamilton County, the home location of Cincinnati Children’s, more than 36,000 children have asthma, including more than 13,000 covered by Medicaid. For years, those Medicaid children have endured poorer outcomes including less well-controlled symptoms, more missed days of school, more-frequent emergency visits, and more.

Cincinnati Children’s provides more than 90 percent of inpatient services for the children of Hamilton County and an estimated 65 percent of their emergency needs. General pediatric clinics here provide primary care for about 34,000 Medicaid-insured children.

Within that sphere, asthma accounts for about 1,000 hospitalizations and 2,500 emergency department visits a year. In addition, more than 7,000 patients receive long-term asthma care from pulmonary specialists here.

Unsurprisingly, improving asthma outcomes has been an ongoing high priority for Cincinnati Children’s.

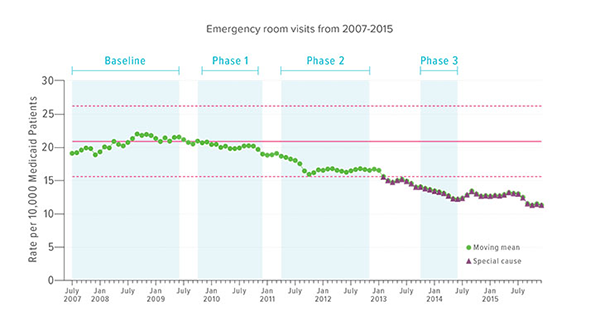

The medical center launched its Asthma Improvement Collaborative in 2007, with improvement efforts kicking off in 2009. In 2010, medical center trustees made asthma improvement one of four core elements of a five-year strategic plan.

A three-phase set of improvements flowed from the collaborative’s efforts. The first focused on hospital-based changes, the next on outpatient care, and the third on a wider set of community goals.

INPATIENT FOCUS ON MEDS-IN-HAND

Specific goals included reducing the asthma-related hospitalization rate from a rolling 12-month mean of 7.2 to 5.8 per 10,000 patients per month; and reducing emergency visits from 20.9 to 16.7 per 10,000 patients per month.

One of the most important learnings uncovered by the network was that vital asthma medications often went unfilled at local pharmacies, even in the days after hospitalizations. So one of the first steps was to change practices within the hospital so that families left with a full month’s supply of medications in-hand.

In 2008, just 50 percent of asthma patients went home with a 30-day supply of inhaled controller medications in-hand. By 2010, that figure had climbed to 90 percent. In 2008, no child started on a short course of oral corticosteroids in the hospital went home with their remaining doses in hand. By March 2011, that figure had climbed to 70 percent.

“We believe that providing a 30-day supply of all daily asthma medications at discharge was key to observed improvements,” the co-authors wrote in the JAMA Pediatrics paper.

Providing asthma medications at discharge helped overcome difficulties many urban, indigent families can face, be it the simple lack of a neighborhood pharmacy or a complex litany of potential lifestyle-related disruptions.

The change in practice produced results. Among Medicaid-insured children, the rate of return visits to the hospital within 30 days of initial discharge decreased by 41 percent; from 12 percent to 7 percent.

OUTPATIENT FOCUS ON ACTION PLANS

Phase Two improvements focused on baseline asthma control among children served by the medical center’s primary care clinics. Teams implemented a bundle of asthma best practices that included consistent collection of asthma control testing data, working with families to create asthma action plans, and enrolling the highest-risk families in care coordination programs.

Two challenges surfaced. Some families needed stepped-up training on how to manage asthma at home, whether or not they had easy access to a pharmacy. Others faced clear, ongoing trouble picking up medications. This led to working with a local pharmacy to create a targeted delivery service for high-risk asthma families.

By the end of June 2015, the effort enrolled 763 patients into care coordination programs. Of those, 394 “graduated” with demonstrated improved understanding of asthma management. Meanwhile, 345 families received medication delivery through the pharmacy partner.

These efforts made a difference: the percentage of primary care patients with well-controlled asthma improved from 48 percent to 54 percent during the study period.

COMMUNITY FOCUS ON SCHOOL-BASED SUPPORT

At the wider population level, the learning network identified shortfalls—and opportunities—related to screening and communication. In response, the network focused on building a deeper relationship between Cincinnati Children’s, the Cincinnati Health Department, and the Cincinnati Public Schools, the county’s largest school system.

“School nurses were crucial,” says Mansour. “We were fortunate that we could build strong relationships with our partners in the health department and the school district who shared a common vision.”

The hospital helped school nurses identify all of the students known to have asthma, many of whom had not been revealed by routine school information requests. Then the hospital provided training, equipment—and in some cases extra sets of hands—to help school nurses do more asthma control testing.

With family permission, school nurses also received limited access to the hospital’s patient records so that nurses could coordinate care and stay informed about changes in medications and treatment plans. This allowed nurses to intervene in some cases long before lingering miscommunications and other care disruptions escalated into a serious asthma exacerbation.

By the end of the study period, more than 80 percent of CPS students with asthma had been screened. Those scores indicating poor control were referred to their existing doctors, or to new medical homes, including school-based health centers.

“We believe that the bundle, which included in-depth risk assessment, directed education, medication delivery, and robust connections with hospital- and community-based partners, including schools, promoted lasting relationships with families and extended the reach of primary care,” the co-authors wrote.

Two well-established, local healthy housing programs also played roles. The CLEAR program supports families facing home-related asthma risks, while the Child HeLP program connects families with legal aid services when housing concerns emerge. Both programs help get city health officials involved when code violations affect child health.

THE WORK TO REDUCE ASTHMA RE-ADMISSIONS CONTINUES

Overall, this five-year, phased approach contributed to decreasing asthma-related hospitalizations from 8.1 to 4.7 per 10,000 Medicaid patients per month. Asthma-related emergency visits fell from 21.5 to 12.4.

“This approach is now baked into how we do our work,” Mansour says. “Would other communities do this exactly the same way? Perhaps not. But if you have leaders with the will, and partners with a shared vision, I do believe this approach is replicable.”

Andrew Beck, MD, MPH, a study co-author based in the Divisions of General and Community Pediatrics, and Hospital Medicine, says economic incentives also may influence how far this asthma care model spreads beyond Cincinnati.

“A unique aspect of this project was the taking ownership for a population-wide metric. This went beyond just the children within the care of Cincinnati Children’s,” Beck says. “If compensation for more care delivery systems becomes tied to keeping patients out of the hospital, this type of work may become all the more important.”

Looking ahead, work to enhance school-based asthma care continues.

A two-year program that ended in 2017 followed 21 CPS students at three schools located in neighborhoods with high asthma hospitalization rates. The project included teleconferencing conducted at school between children and asthma specialists, providing patients with electronic inhaler monitors, and providing medication bottles with digital caps that can be synced with smart phones.

“Overall, we showed that reducing asthma exacerbations with a program like this is feasible,” says Theresa Guilbert, MD, MS, a pulmonologist who oversaw the program. Now Guilbert is applying for a grant to expand the program to 26 schools.

Mansour says it was both sobering to recognize just how complicated life can be for families covered by Medicaid, and a joy to be able to make a difference.

“As we helped eliminate some barriers, these families were able to see their children do better and feel better,” Mansour says. “For some of these families, their kids had been living in such chronically poor control that they didn’t even know what life with a healthier child could look like. There was real joy in hearing those stories.”

—By Tim Bonfield

(This article originally appeared in the Winter 2018 issue of Research Horizons)

| Original title: | Association of an Asthma Improvement Collaborative With Health Care Utilization in Medicaid-Insured Pediatric Patients in an Urban Community |

| Published in: | JAMA Pediatrics |

| Publish date: | Nov. 1, 2017 |

Research By