A POWERful National Registry Brings Collaboration and Big Data to the Battle Against Pediatric Obesity

Post Date: June 30, 2019 | Publish Date: Summer 2017

“The biggest lesson is that success correlated with the number of dietitian visits.”

In the fight against pediatric obesity, there is power in numbers and, increasingly, numbers in POWER.

When Shelley Kirk, PhD, RD, launched the Pediatric Obesity Weight Evaluation Registry (POWER) four years ago, there was no national registry of pediatric weight-management programs.

Today, POWER includes 33 medical institutions in 21 states, each contributing standardized data that can help determine which intervention strategies improve health for obese children, and just as importantly, which ones do not.

Cincinnati Children’s serves as the Data Coordinating Center for the POWER project. Kirk, of the Heart Institute, and Eileen King, PhD, of the Division of Biostatistics and Epidemiology, lead the work.

“If you’re starting a registry with limited resources, we have demonstrated that this can be done,” Kirk says. “We proved that we could do it, as collaborators instead of competitors.”

Now, the network has started producing meaningful results, including more accurate snapshots of the prevalence and impact of childhood obesity. This registry also highlights the valuable role for multi-component interventions to control body mass index (BMI) long-term. Those interventions can include medications, nutrition, physical activity and behavioral counseling.

CHILDHOOD OBESITY RATES LEVELING, BUT STILL TOO HIGH

In February 2017, a study based on POWER data appeared in the Journal of Childhood Obesity. The study analyzed data from 3,643 youths with obesity, including demographic and clinical parameters. Two-thirds of the children in the study were severely obese, in an era when one of every three children in the U.S. is overweight or obese.

With a four-fold increase in childhood obesity rates over the past several decades, there are reasons for guarded optimism. The data show that the rate of increase has slowed, but it has not stopped. This is particularly true for those with severe obesity, Kirk says.

IMPROVED INTERVENTIONS HELP WITH WEIGHT MANAGEMENT

In May, Kirk also gave a platform presentation at the annual meeting of the Pediatric Academic Societies in San Francisco.

She presented data showing that long-term monitoring by health professionals is crucial because so many kids struggle to ad-here to the lifestyle recommendations for diet and exercise made by their weight-management programs.

Unlike electronic apps and other device-based tactics designed to engage kids in improving their eating habits and increasing activity level, Kirk says the data show that direct contact time with professionals actually works.

DIETITIANS MAKE A DIFFERENCE WHEN TREATING OBESITY

In an April 2015 study published in the Journal of Childhood Obesity, Kirk worked with Robert Siegel, MD, Medical Director of the Center for Better Health and Nutrition to examine the impact of visits with registered dieticians on the BMI outcomes of obese children as part of their intervention program.

They found that each additional dietitian visit was associated with a 28 percent increased chance of successfully reducing BMI. Overall, the probability of success exceeded 78 percent with monthly dietician visits, compared to 43 percent success rates with minimal exposure.

One big and frustrating challenge: “In some cases insurance coverage for a registered dietitian is limited to three 30-minute visits a year,” Kirk says.

Still, the study was important because it helped set some precedents, Kirk and Siegel say.

“The biggest lesson is that success correlated with the number of dietitian visits,” Siegel says. “Dietitians are very, very important. Exercise physiologists are very, very important. When the family does not meet with a dietitian and an exercise physiologist, the results are generally not good.”

EARLY INTERVENTION MATTERS FOR WEIGHT CONTROL

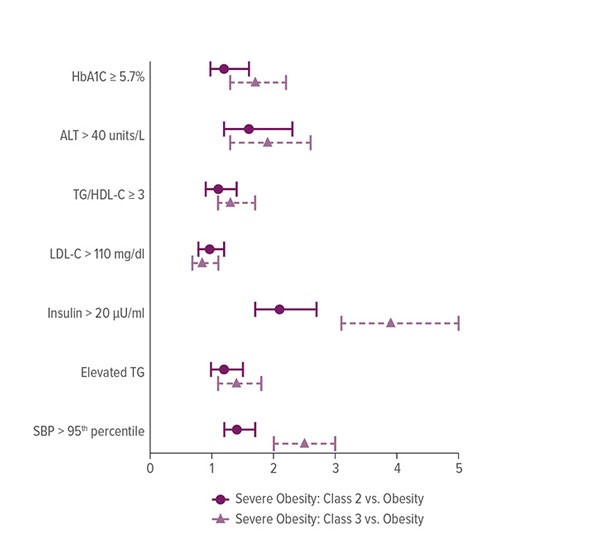

In another paper, published in October 2015 in Childhood Obesity, Kirk and researchers from 13 of the institutions in POWER analyzed data on 6,737 obese patients ages 2-17.

The team studied laboratory tests, blood pressure and demographics. They also examined the relationships between BMI status and co-morbidities.

Their finding: By the time most obese youths enter weight management programs, it is too late to avoid significant co-morbidities. Yet convincing families to enroll kids earlier, at lower weights, has been an uphill battle, Kirk says.

POWER’S FUTURE, ONCE UNCERTAIN, TAKES FLIGHT

Creating the POWER registry was long overdue, Kirk and Siegel say, but the effort has demonstrated that dozens of pediatric hospitals can team up to collect a valuable, uniform set of data.

“We’re here to stay,” Kirk says. “Nobody knew we even had a future when we started. But Cincinnati Children’s, including the Heart Institute, has been there the whole way.”

The next step is to secure additional sources of funding. So far, the POWER project has been primarily funding by enrollment fees covering each two-year cycle ($5,000 for 2014-2016; $6,000 for 2016-2018) from each participating institution. However, additional funding provided by the Heart Institute to cover needed administrative and faculty support during the first cycle was key to the project’s success.

Kirk has been invited to speak about patient outcomes based on POWER at a September workshop sponsored by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases. The audience will include scientists with expertise in a range of specialties relevant to obesity, including genetics, endocrinology, epidemiology, psychology, behavioral medicine, and bariatric surgery.

She can’t wait.

“We don’t have National Institutes of Health funding now,” she says, “but this meeting provides an opportunity to showcase the work of POWER and make important connections that can help secure future funding. We know that pediatric obesity research is important to NIH and we believe POWER offers a needed resource to address this important health issue. That’s the vision we have for POWER going forward.”

—By Tom O’Neill

(This article originally appeared in the Summer 2017 issue of Research Horizons)